The next leg is to Moscow. I have wasted

$150 on a Russian transit visa because the airlines are under the erroneous

impression that one is required. I know that is not true, but do not want

to be denied boarding. The confusion arises because flights to destinations

outside Russia but within the former Soviet Union leave from the

"domestic" terminal on the other side of the airport. Anyway,

it works as it supposed to: instead of going through immigration one goes to

the transfer desk, where the transit passengers are driven to the other

terminal. The transfer gal, inspecting my passport, remarks "Oh, I see

you have a Russian visa. Would you like to visit Russia " Yes I do,

but do not have time. Cyrillic has been jettisoned in favor of our

Latin alphabet. Although Russian is still widely understood. English is

now taught in the schools. Signs are either in Cyrillic or

"English," depending on vintage, but not both. Interestingly,

the currency is still only in Cyrillic. Speaking of parties, the European Development

Bank, one of the international money wasting bureaucracies funded largely by

the US taxpayers, has chosen Tashkent for its annual meeting beginning

tomorrow. The red carpet has been rolled out for the 2500

attendees. The plane is full. I mix in with the bankers and breeze

through passport control. At the exchange desk I get a brick of brand new

1000 sum notes -- the highest denomination printed -- worth $1

each. Lots of folks standing around being helpful. It

is only at customs where I am discovered as an imposter. My luggage

trolley is confiscated (for bankers only), and I am banished to tourist

Siberia, where there are no services, only brusque officials.

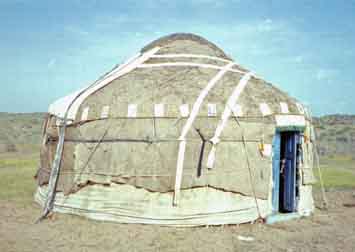

I miss out on the free hotel transfer offered to the bankers. From Samarkand we head out into the Kuzyl Kum

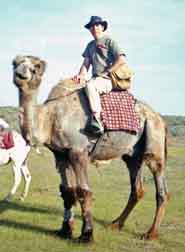

desert for a night in a yurt camp. The afternoon entertainment is a camel

ride to a ranch, where we arrive in time for the camel milking. the

process requires three people: one to restrain the back legs, one to hold the

bucket, and one to milk. No milking stool required -- it's all done at

shoulder height. These are bactrians (two-humped Asian camels), which are

much more comfortable than dromedaries (one-humped African camels); you just

sit between the humps. I could have skipped the singing and dancing

around the campfire later on, but it all comes with the territory. In the

morning we skip the 4WD and return to town on camelback.

Directly across from our hotel is the synagogue,

the last remnant of an ancient and once large Jewish merchant community. (Why

have the Jews left Because they CAN!) It's not much more than a

simply decorated room. As photos on the wall attest, it is a mandatory

stop for pandering American politicians (including that witch, Hillary).

There must still be a fair amount of tourist traffic because the street urchins

know a smattering of Hebrew. From here we head north. A day of driving

brings us to another yurt camp, this one beneath the walls of an ancient desert

fortress. I search diligently, but find no gold coins or artifacts, just

pottery shards. Luckily they do not display it all. If you

like modern art, it is good. Amazingly, some artists spent years studying

and working in Paris but then came back to Stalinist rule. Artistic

freedom came at a price: one guy was accused of "formalism" (he

painted still lifes) and sent to the gulag; in Siberia he continued to paint

miniatures using cigarette papers and burnt matches; his prison art is also on

display. We continue north to the Aral Sea, or at least

where it used to be. Once the world's fourth largest inland sea, it has

diminished by 70% and continues to shrink because the rivers feeding it have

been diverted for irrigation. The only water that reaches the sea is

saline, pesticide-laden runoff from the fields. Various international

do-gooder organizations continue to "study" the problem, but their

solutions do not include the obvious: stop diverting the water. (It ain't

gonna happen.) Even worse, most the water taken is either lost or

wasted. Formerly home to a large fishing industry, the sea is now

completely dead. The town of Moynak was a fishing port but is now

60 miles from the shoreline. The cannery is long closed and abandoned.

Nobody works except in government jobs (a Democrat paradise). There is a

museum of the vanished sea and fishery that displays exhortations such as

"People, Save the Aral Sea!" (As if slogans will solve the

problem.) The point of this long trip is to visit the

ships' cemetery, where hulks of fishing boats lie stranded in the desert.

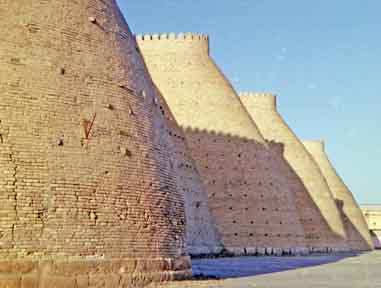

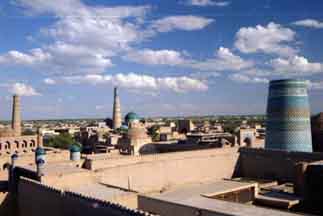

The really big ships were cut up for scrap and now exist only in photographs. On to Khiva, a rival khanate to Buchara, and the

most remote and intact city on the Silk Road. For centuries was a center

of brigandry and the slave trade, which didn't end until the Bolsheviks put a

stop to it in 1920 (by making everybody legal slaves). Our hotel is kind of a spartan place, but has a

great location -- within the walls and just steps from the center of the old

city. Also staying here are a Japanese photo tour (tiny, wizened people hauling

around enormous lenses and tripods) and a Bollywood film crew. Although the city is old and looks great, the

buildings are of comparatively recent vintage. Earthquakes and invasions

have destroyed the city many times. Alexander the Great and Genghis Khan

both came through. Khiva is primarily a museum city, but a few thousand

residents still reside within the walls. They reallylike Americans in Uzbekistan.

Most of the tour groups are, predictably, French (they sympathize with the

politics and economics). Everywhere I go people ask "Francia " When

I respond "Amerika," they break into broad smiles and give me the thumbs

up. They are Muslim -- some more, some less -- but they all hated the

Taliban, and are very grateful to the US for the recent invasion. No

problems with Operation Iraqi Freedom either. It's our last night, so I agree to the

ballet. Can't argue with the price: 2nd row orchestra, $1.50. On

the way there, walking down the main pedestrian mall, the Swiss guy and I get

stopped by the police and taken to the substation. They don't speak

English. My interrogation is limited to examining my passport and visa

and asking "tourist and "Uzbekistan good The Swiss guy was

foolish enough to respond in Russian, which resulted in a far more intensive

questioning. In the end, they wave us off. Our leader tells us

later that is the classic Tashkent shakedown (it doesn't happen elsewhere) to

try to extort money. With me they must have decided not to mess with

Americans or they just gave up tying to communicate. The Swiss guy had

little money on him, so they struck out there too. Now that the bankers

have gone, the cops are probably making up for lost time and revenue. Ballet report: giant cast, lavish costumes,

ornate sets, 40 piece orchestra. The offering was "Esmeralda."

I don't think it could be performed in America because it portrays unfavorable

ethnic stereotypes (gypsies stealing babies) and is insensitive to the plight

of persons with congenital deformities (Quasimodo). I find the plot to be

totally unbelievable -- everyone knows that hunchbacks can't dance worth beans.

The music isn't too bad, and I endure the prancing about, figuring it is

slightly more entertaining that driving across the desert in a minivan without

aircon. We finish our final, celebratory meal at 10

PM. No point in going to bed, cuz I gotta leave for the airport at 2

AM. The flight back is fine. You know how

airlines always serve dinner on international flights no matter how late the

hour Well, at 4:30 AM the cart comes by and I am asked, "chicken or

fish " I was figuring on being back in Amsterdam in the

morning, but it turns out that I misremembered. I have most of the day in

Moscow, so I decide to eschew the sterile airport transfer and make use of my

expensive visa. I join the scrum at the passport control counter.

No problems, just slow. Doing it the Russian way (minivan to the metro), I

am in Red Square for less than dollar. The problem is that I have no map

or tourist information and have to rely on the my failing memory to find my way

around. The State History Museum was deemed too dull to

visit my first time, and it was closed for renovations the second time.

They have now revamped it and it is quite absorbing. The special

exhibition is on the events of 1943 (next year's theme will probably be

1944). It was the turning point in the war, for sure, but it is presented

as a year of unalloyed victory and triumph. There is good display of

posters -- I would have bought a catalog if they had one. The weather is cold and wet, not so conducive to

walking around. I go to where I though the cosmonaut museum is, but I

must have misremembered that too. Anyway, it's time to go back to the

airport. Amsterdam is also cold and wet. I have

been awake all night plus there is a three hour time change, so by the time I

get to the hotel I am ready for bed.

The downside of living in Jacksonville is

that it takes forever to get anywhere. Central Asia is no exception.

The first leg is to Newark. During the

layover, I hang at the club. Dubya is giving his speech from the aircraft

carrier deck tonight, preempting all channels. I am in the bar when he

comes on. Hoots and catcalls, followed by everyone making a conspicuous

display of ignoring Our President. I retreat to the big screen

lounge. The audience which a few minutes early was reverentially silent

during a Seinfeld rerun is now chattering away. I shush them. They

shuffle out, probably to go fill out their pledge cards for the Clinton

Library.

The next leg is to Amsterdam. The new

in-flight entertainment system gives even the steerage pax a choice of

movies. Some choice. "The Hours" proves unwatchable.

"Daredevil" is about a blind lawyer who can't stand to see people he

knows are guilty acquitted so he uses his superpowers to kill them later.

(Guess that beats staying up all night writing appellate briefs.) The

other offerings are not even worth mentioning.

I have about a 20 hour layover in Amsterdam,

where I check into a very comfortable airport hotel. It is tulip season,

so I travel to Keukenhof Gardens in Lisse. It's only open 2 months a year

in the Spring. Operated by the bulb growers as a showcase, it has 7+

million bulbs planted on 80 landscaped acres. It's supposed to be one of

the three most photographed places in the world (don't ask me how they come up

with that statistic). Anyway, it is spectacular. The lousy weather

-- overcast with intermittent showers -- keeps the crowds down.

The flight on Aeroflot is pretty good.

They use Boeings and Airbuses. The food and service beats KLM. In

order "to conform to international standards," they have recently

banned smoking on board. This new rule, of which we are continually

reminded, is not popular with the Russians.Uzbekistan is in the heart of the "stans,"

surrounded by Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kygyrzstan, Tajikistan, and

Afghanistan. (During the czarist era it was all considered

"Turkestan.") Now independent, it is part of part of the CIS (successor

to the USSR) but quite happy to no longer be a Russian colony. The commie

trappings are all gone, and the streets have been renamed. In the center

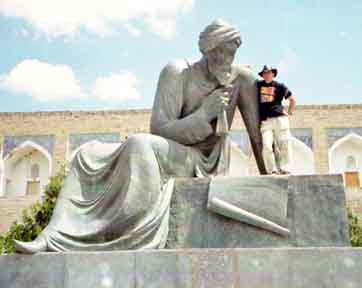

of every city and town the statues of Lenin have been replaced, many by ones of

Navoi, a poet. Not that they are such a bunch of poetry lovers -- the

other candidate was Tamerlane, but I suspect that is much easier to melt old

Vladimir into a guy with a turban instead of one on horseback.

But that's all cosmetic. Like other

"stans" that comprised soviet central Asia, very little has changed.

Uzbekistan is still a one party totalitarian state run by the same corrupt

thugs. There is very little economic freedom and even less in

the political realm; the communist bosses simply renamed the party.

I've got plenty o' nothing

In the morning the group meets up. We are

five: 2 Australians, a German, a Swiss, and me, plus Australian leader.

Our city tour follows. Tashkent is a big

place. It was the fourth largest city in the Soviet Union and is the hub

of central Asia. It is also an ugly city -- mile after mile of hideous Soviet

apartment blocks and gray concrete construction. Tashkent is an

ancient city and was a stop on the silk road, but there is not much to see:

some old mausoleums which also being visited by officials delegations

accompanied by camera crews. There are lots of cops everywhere.

The history museum is closed. Our local

guide quips: "Because the old history is no good and the new history has

not yet been written.

A giant statue of Tamerlane sits on a spot that

has been occupied by six different statues in the past 100 years, his most

recent predecessors being Karl Marx and, before that, Stalin. He stands

at the head of Broadway (formerly Karl Marx Street). Tashkent was the

also home of the world's tallest Lenin statue, but, alas, no more.

Dinner is a pleasant introduction to the general

price level: a lavish repast for six is $27, including tax and tip.

Monday morning we drive to Samarkand by public

minibus. Rather than wait for enough passengers to arrive to fill all the

available seats, we pay for the empty seats, greatly increasing our comfort (it's

a five hour drive) at a cost of $4 each. The road runs through

Kazakhstan, but the border is currently closed so we have to detour. The

borders were arbitrarily drawn by Stalin, which mattered not in the days of the

Soviet Empire. These days, it's a problem as roads and train lines run

through neighboring not-always-friendly countries. Rather than deal with

the issue through diplomacy, new, circuitous rail lines and roads are being

built.

Samarkand was chosen as capital by Tamerlane,

who claimed to be a descendant of Genghis Khan and who reconquered much of the

same territory: all of central Asia; much of the middle east; almost to the

gates of Moscow and Constantinople. His sack of Delhi provided much of

the loot for his building program. Gigantic mosques and madrassahs

(Islamic universities) dominate. Very photogenic -- it's all in good shape cuz

it's all new. Earthquakes over the centuries have insured that everything

which has not been restored or rebuilt is in ruins. Many of the structures

were just recently reconstructed, and more are in process. It's all

eyepopping. (You've probably seen pictures of the Registan.) The

dynasty only lasted five generations, after which they repaired to India and

became the Moguls.

The Yurt Hotel Saddled up

We continue on to Buchara, another stop on the

Silk Road and one of the last of the central Asian khanates; it lasted until

conquered by the Soviets in 1920. It was known as "holy

Buchara," although a description of the times sounds exactly like life

under the Taliban. (Keep in mind that the modern borders are just that,

and for the millennia preceding vast tracts of the region, including modern

Iran and Afghanistan, were all parts of various kingdoms and empires)

We have three nights in Buchara, a walled city

filled with mosques and minarets. It's extremely photogenic and very

tourist friendly with lots of cool stuff for sale. Some buy carpets; I

buy hats.

It's

May 9th, Victory Day in The Great Patriotic War, known in the west as World War

II. The war memorial is covered in flowers, and everything is closed for the

public holiday. Old men wear their medals. Having lost European

Russia, it was from places like this that Stalin obtained the millions of

conscripts to send to the front. Every family lost one or more members.

No parades or military displays, just solemnity.

Dinner is the best yet. Why To

accommodate our western palates they have trimmed the fat. In central

Asia they love animal fat, so your skewer normally consists of kabobs of fatty

meat alternating with blobs of fat. Also, we are served beef, a pleasant change

from sheep. There is not a great deal of variety in the national menu:

fatty soup, fatty meat, rice, a few stewed vegetables. There is not much

in way of fresh fruit or vegetables. The bread is OK when fresh.

In the morning we continue on past more ruined

forts until we arrive at Nukus, a grim, unappealing, Soviet-looking city.

It is the regional capital and the unlikely home to perhaps the world's

greatest collection of Russian modern art. During the Stalinist era, the

only acceptable style was social realism. (Think "heroic

workers" statues and posters.) Modern art was censored or

banned. The director of the Nukus Art Museum took advantage of this

remote location to assemble a treasure trove of works from the 1920s and 1930

s, many acquired for pennies or from salvage. Now they are justifiably

proud of their collection, which numbers in the tens of thousands.

We are in a homestay not on the presidential

route, the street is more potholes than paving. In the morning there is

no running water -- the joke is that the water has been diverted to the

fountains in the museum plaza. Our hosts speak no English, but are very

nice. She is a lawyer for the army and he is a microbiologist.

Nukus was home to a secret soviet germ warfare lab -- it is supposed to be

closed now, but who really knows

It's the end of the trip. Two weeks have

gone by. We fly back to Tashkent. Sure beats driving. We arrive in

time for me to visit the Defense Museum. I am disappointed that all the

stuff celebrating the revolution and Russian conquest has been replaced by

displays on Tamerlane and of the modern Uzbek military as a vital and

integrated part of international cooperative efforts. The floor devoted to the

Great Patriotic War is intact. What I like are the exhibits on the part

the local boys played in the taking of Berlin. That was the Nazis worst

nightmare: hordes of Asiatic troops sweeping across Germany. No other

tourists in sight, just bored looking youth groups.

I had entertained thoughts of bicycling through

the tulip fields, but scrub that. Instead, I undertake a whirlwind tour

of the Randstad. First, back to Amsterdam: it is as I remembered.

Escaping the filth and crowds, I move on to Haarlem: a decent looking square,

but otherwise unimpressive. Heading south through the bulb fields, I see

that the fields have been mowed and the flowers gone. Next, Delft:

pretty, but mucked up by too much tourist stuff. In Delft I visit the

Army Museum, which is excellent and evenhanded to a fault, e.g., equal space given to

resistance and collaboration; a warts and all display on postwar

decolonization, with a special exhibition Goodbye to New Guinea. Next stop, The

Hague: some good sights but almost lost in the large modern city.

Finally, Leiden: worth a look.

The last morning I spend in the hotel typing

this trip report. Can't fall behind; leaving again in less than a month.

Trip date: May 2003