When I receive an email from my favorite tour company announcing an experimental new trip to seldom-visited areas of China, North Korea, and Russia, I'm on it like a crow on a June bug. The trip sells out in just a few days Most of the participants are expats already living in Asia and for whom transportation is less of an issue. The key to my making it happen is being able to redeem frequent flyer miles at “regular” levels. Better yet. I get business class.

The trip is to the Tumen border region where the three countries meet. We will start in China, cross the Tumen River into the North Korea’s Rason Free Trade Zone, travel down to Chongjin and Mt. Chibo, then cross the river again into Russia and continue on to Vladivostok.

A couple of week before departure the first wrinkle surfaces. Local permission has not been obtained for Americans to stay in Chonjin. That means four of us would get bussed back to Rason at night and no Mt Chibo. That's OK, I'll miss out on the Ritz-Carlton Chongjin, and I've seen enough Manchurian rocks. I'm still in. I send off my application to the Russian consulate for a tourist visa.

What an ordeal! I've gotten one from them three times before, but it's never been like this. List all educational institutions attended since age 16 with dates and course of study. Last two job with supervisors and reason for dismissal. Details of all military service. Experience or training in arms, explosives, nuclear materials, biological warfare. (say, are they recruiting?) All countries visited in last ten years (a LONG list for me). All organizations to which you belong.

Next problem: we learn that NO ONE may travel to Chongjin/Mt. Chibo. The Nork tourist agency with which our outfit is dealing has recast their previous confirmation of permission as mere anticipatory approval. Hurriedly reworked, the trip is now shortened to 8 days from 10. Three people drop out; the remaining 17 are stalwart.

As my departure date approached, I am still sweating on my Russian visa. The consulate is tight-lipped on when they will be done. I think the message they are sending is that everyone should pay the additional fee for expedited processing. Finally, the day before my departure, Fedex delivers my passport. (Not that I can go anywhere without it.)

I arrive in Beijing in accordance with the orginal schedule, two days early on the revised one. I am staying at a budget but stylish hotel. In addition to a glass-walled “fishbowl” bathroom, the room comes equipped with an actual fish. Next to his bowl is a card introducing himself and advising me that me he is on diet so please don't feed him and inviting me to try his rubik’s cube, also next to him. If I can finish three sides he'll buy me a drink downstairs.

The room has wifi, but in China Facebook and Youtube are blocked. Wikipedia has a page listing the sites that are blocked, but that page is blocked too. Google works, but is kind of screwy.

I get a local SIM card for my cell phone. They are price according to how lucky the number is. I risk doom and pay $1.50 for the cheapest, unluckiest phone number. In America phone numbers are seven digits plus area code. There are more Chinese than there are nine digit numbers, and that’s even before you get to the area codes. Mobile phone numbers are eleven digits, as is mine.

I visit the video store. The pirates are lagging: Toy Story 3 is on the shelves, but only in low quality (but first quality packaging and cover art).

In the evening, I meet up w// my buddy from Vancouver who is also doing the Tumen trip.

We have another day to kill so we ride up to the former Olympics venue. It costs 50 yuan ($7.50 US, but equivalent to $50 in earning and purchasing power) to get into the main stadium, the Birds Nest. It is about as exciting as you would expect an empty stadium to be. (It, along with the other specially-built Olympic venues, has not been used since the Games.) Inside, you can view a display of wax figures of former heads of the IOC, and for a mere 25 yuan have your photo taken with one. There is a official licensed products store featuring scale models of the Birds Nest (in glass, plastic, ceramic, chocolate, and many limited edition versions), Birds Nest key chains, magnets, medallions, jewelry stamps, and everything you can think of except actual birds nest. So why can't the marketing geniuses come up w/ Official Birds Nest Birds Nest Soup?

Friday we begin the trip by flying to Yanji, and area heavily ethnically Korean. I’ve been here before (on my Manchurian trip); it’s the gateway to Changbai Shan, the mountain that forms part of the China-Korea border (the Koreans call it Mt. Paektu). The signs and billboards are bi-lingual, and the restaurants offer Korean cuisine. The hotels cater to South Korean visitors, not westerners.

On Saturday I get up with the sun, which means 4 AM because all China is on a single time zone and we are east and north. I don’t think to visit the market, but someone who did reports that it is canine city, live, ready to cook, or freshly roasted. If dog is not your fancy, a shop near the hotel sells specialty products from Russia, including canned bear meat and moose meat.

Later in the morning we get underway, driving first to Tumen city on the border. Like Dandong at the western end of the border, Tumen attracts Chinese tourists curious to a peek at a foreign country. They rent binoculars or peer through telescopes for a glimpse of North Korea (there are only fields on the other side) and can walk halfway across the bridge spanning the Tumen River. Note that I say “they,” because only Chinese are allowed on the bridge; we are not. There is no legal restriction, only pure racism by the border guards. No such invidious discrimination is practiced by the vendors and shops that sell North Korean cigarettes, stamps, money, and other souvenirs.

Tumen is part of a free-trade zone, and the city fathers are eager for economic development. To further this end, they have set up a multimedia exhibition. An electronic wall screen with expanding concentric circles radiating outwards shows the city it to be sited at the heart of Asia and the Pacific rim. On the roof is a viewing platform facing the river. It’s pretty much the same view as at ground level, except you can't take a picture if you're white. We do anyway. The guard then won't let us leave until he checks each camera and makes us delete the offending images. No real loss: the picture sucked; the only reason I took one is because had to climb three flights of stairs to get there. Nonetheless, I am so incensed that I cancel my plans to built a factory here. It’s a matter of principle.

There is a border post at Tumen city, we continue eastwards to Hunchun where there is another bridge across the Tumen River closer to our destination. There, we alight our Chinese bus and board an old rattletrap just to cross the bridge. On the other side is the North Korean “welcome” station.

Although we are the only ones there and have all the right paperwork, it still takes hours to get through customs and immigration. They spent twenty minutes inspecting the luggage of the first person in line. I am one of the last, and by the time my turn comes they have either lost interest or are anxious to go home so basically wave me through. Our books and videos are supposedly inventoried. We surrender our cell phones. (Since we will be exiting at the different location, they are packaged up with many seals and given to the driver. My iPad is a great hit: I have already programmed it for DPRK mode -- an automatic slideshow of portraits of the Great Leader, Kim Il Sung, and his son and successor the Dear Leader, Kim Jong Il.

It is dusk by the time we board our tour bus and meet the friendly and relaxed (by North Korean standards) Mr. Mun, our guide, and the taciturn Mr. Kim, the minder (and probably the real boss). We set our watches back by one hour and fifty years. In the DPRK the calendar starts at Juche 1, the year the Great Leader was born; next year will be the centennial celebration of that august event. So, the theme for this trip is our running joke: “we’re gonna party like it’s Juche 99!”

If Pyongyang airport or the DMZ crossing at Panmunjon are the ceremonial gates of the DPRK, we are entering through the back door. Forget about paved roads. The weather deteriorates, but there is no danger from oncoming traffic. There are pedestrians, a few bicycles, and the occasional oxcart, but no other vehicles. For the hour and half drive to Rajin. Mr. Mun keeps us entertained with their version of Korean history and karaoke, including a rendition of that famous Korean ballad Edelweiss.

When we reach Ranjin we proceed straight to dinner, where we are greeted by platters of giant, superfresh prawns, whelks, and other seafood, and, best of all, no kim chee. Then we check into the Namson Hotel, built in 1935 by the occupying Japanese (here, they pointedly say “Japs”) as officers’ quarters. I think we are the only guests. The rooms are comfortable enough. There is only one channel on the TV, but the set has the capacity for three more, so it’s cable-ready.

The hotel is right on the main square of the city. Around it are various government buildings and apartment blocks. Most dwelling are five to seven stories, the maximum you would build without elevators. (I read that in Chongjin the buildings reach eighteen stories but the elevators were never installed.) My room, Room 227, overlooks the square. Over the door to the adjacent Room 225 is a red plaque proclaiming that the Great Leader stayed there in 1959 and again in 1970. Our tour leader cheekily asks if he can move to 225, and they look at him like he suggested that it be firebombed. “That room is not for living.” We are promised a tour of it the next day. (But they don’t come through; maybe if we had a better attitude.)

At 6 AM Sunday loudspeakers blast rousing and inspiring music across the square. It is already busy, with people bustling across, some pushing handcarts, and some on bicycles (both sexes—in Pyongyang, only men are allowed on bikes). Are they celebrating because it’s July 4th? Are they racing to line up for the iPhone 4 release? No, actually, Sunday is their day off and it’s market day (more on that later).

Before our bus leaves we are allowed in to the square to take pictures in front of the propaganda boards (which is way more freedom than we were allowed in Pyongyang. But no photos of people! However, from my room I can snap away unseen by the minders.

We first stop so they can show off the Victory Petrochemical plant. Like most industry in this bankrupt country DKRP, it is closed. (No money for feedstock.) We don’t get very close, just an overlook obscured by fog. A great photo op presents itself: a man with a bullock and plow, but it’s not allowed. Why would one site a petrochemical plant inland and away from any oil or port? The Great Leader declared it so. No further explanation needed.

We drive to the coast and take a boat ride to a marine preserve in the Sea of Japan, (or, as the Koreans insist, the “East Sea”) . I think lack of fuel limits our excursion since we board, chug straight out to a pod of seals (all we can see are their heads), and come straight back. At dockside the locals have set up an impromptu market to sell us dried fish. Are we expected to bring it home out suitcases? There are a few other items on offer. Someone buys a package of walnuts; they taste like fish.

From the boat we could see the waterfront Emperor Hotel and Casino, our next stop. Built by gambling interests from Macao, it all marble, crystal, and gleaming brass, straight out of Vegas. The “Please Do Not Spit” and other signs are in Chinese, Russian, and English (but not Korean). Although open, it is deserted. It was built to lure Chinese gamblers, but the casino was forced to close after more than one Chinese official risked (and lost) public funds at its tables. With the loss of the casino the hotel lost its raison d’etre, but the Norks don’t give up so easily. There are doormen to greet the non-existent guests, lobby clerks to check them in, and bellmen see them to their rooms. Unhindered by the need to attend to guests, the staff has plenty of time to clean and polish.

We must be considered an unruly group, because we have picked up an extra minder, Mr. Li, who we immediately dub Mr. Creepy. In a land a midgets he is tall enough to play basketball, but, like everyone else, is rail-thin. The food situation is never good in North Korea, and this region fared even worse than most during the famine.

But we eat abundantly well. The area offshore is one of the few productive fisheries in the world that is not overexploited. As much as they have fuel to venture out, the boats bring back a rich bounty. Most is reserved for the elite or processed for export, but we get first cut. We have a fabulous lunch of giant prawns, scallops on the half shell, crab legs, squid, and much, much more, all absolutely fresh and perfectly prepared. When with us, our guides eat the same food and devour it like they were just released from a POW camp. The only people we see who look well fed are the kitchen staff. The worst business opportunities in North Korea must be the Weight Watchers franchise and the Slim Fast distributorship.

After lunch we work off the calories with an impromptu beach soccer game against some Russian railway workers, easily distinguishable by their barrel bellies. When the ball rolls under the electrified fence that lines the beach, there is some hesitation about retrieving it. No worries -- the power isn’t on, just watch out for the barbed wire. A sad ending: Russkies, 3: Rest of the World, 1. Unlike certain teams in international sporting competitions, at least we don’t have to fear torture and imprisonment when we return to our home countries.

We visit a big seafood processing plant. Today they are doing squid. As the fresh squid comes in by the boxload on conveyers, dozens of women clean and cut them up by hand. There is only a single viewing port so we don’t see what happens after that.

Part of the facility manufactures Pine Mushroom Liquor for export. After a taste, we know why it’s not on the top shelf at your favorite bar. We want to buy some for souvenirs anyway, but they are not set up for on the spot sales. A fair amount of confusion ensues, largely because the bottles are priced in dollars but other currencies are accepted as seemingly random exchange rates and they have no change.

One of the weirder features of the plant is its extensive statue park featuring various tableaux, all the same size and style, of modern workers in offices, labs, and classrooms. None of the heroic size displays depicts anything to do with seafood processing or alcohol production, and none are situated to be readily visible to the workers or, for that matter, anyone else.

The last item on the day’s agenda is a visit to the market. This being an economic experimental zone, Rajin has the first officially sanctioned private market in North Korea. Our guides are very nervous about our visit: we must stay together in the group at all times and leave our cameras on the bus.

The market is located behind the Tae Kwon Do Hotel. (So,do you have to fight to get a room?). The surrounding streets are crowded with people coming and fro going, milling about, or passing time. Today they have something worth staring at: us. Our presence alone creates a stir.

The market is indoors and quite large. It is organized by type of item sold. Most of the wares on offer are household goods and clothing from China; what little is still produced by North Korean industry is directed to the state-run stores. We do find something local to buy: little school badge pins. Within the free trade zone the residents are permitted to possess foreign currency so we pay in Chinese yuan. (Foreigners are not permitted to use local currency anywhere in the country.) Just outside are farmers selling vegetables grown on home plots; grain and other staples remain a state monopoly.

Dinner is at a restaurant, where, once again, we dine like kings, or, more accurately, like Kims. During the meal the power goes out, a regular occurrence. We walk home through the dark streets. The only vehicular traffic is a police car barking orders at pedestrians through its loudspeakers.

On Monday morning, the resumption of the workweek means that we have to go down to the “immigration office” to register. They tell us that we are the first western tour group in ten years.

Yesterday someone asked the guides half-jokingly why there weren’t any taxis in front of the hotel. When we emerged from breakfast today there are four vehicles parked side by side with white roof signs marked “taxi” (in English). I think they left shortly after we did.

The day’s itinerary starts with a visit to a “typical farmhouse” set amidst more modern multistory concrete housing blocks. (Most are five to seven stories, the maximum you would built without an elevator.) This is an historic site: the Great Leader once stopped by here to inquire about the living conditions of the peasants. I didn’t think to ask whether the modcons -- running water (a pump in the kitchen) and electricity (a light bulb and a television) -- pre or postdate the visit. The original family is honored to still occupy the dwelling, but at the price of having tourists troop through their home. Despite the honor of the red plaque, they still rely on an outhouse.

Nearby, at a spring noted for the healthful qualities of its water, women are doing laundry, the usual pounding on rocks routine. Just offshore is the rusting hulk of a freighter. As our cameras go up Mr. Creepy pipes up: “no photo, not beautiful,” thus coining a catchphrase for the remainder of our trip.

At a “historical relics” museum the exhibits are mostly pictures of things that are not here. I guess that’s better than the Rajin city zoo, where our leader reports that when he went they had two ducks, a turkey, a fox, a bear with three legs and a drawing of a monkey. (Why not a picture of a giraffe, or, for that matter, a unicorn?) In a shop someone finds “anti-radiation honey.” We can’t read the label, but wonder whether is contains a caution against using it before a CAT scan lest the image be blank.

In the afternoon we are taken to the Children’s Palace for a show. Before the performance starts, under the guise of go the restrooms we sneak a look at some of the other rooms: children’s drawings of tanks crushing the enemy; displays of the war crimes of the Yankee imperialists; the prisoners of the south half of the country under US occupation. When found wandering, we are escorted back to the auditorium.

The kids are talented and adorable. And TINY, I don’t think one is more than three ft tall. We are told that they are four and five years old, but I suspect that they are older but just stunted. (It is not uncommon for teenage boys to be less than 5 ft. tall and under 100 lbs.) They seemed happy enough while performing but there is not a single smile to be seen during the photos with us afterwards. Perhaps, after all that propaganda, they were scared of us, afraid that we would kidnap and eat them. (The Norks do not smile easily, but, then again, they don’t have a lot to smile about.)

For variety, we switch hotels. We move from the Namson on the main square to the seaside Rajin Hotel. Classified as a “first class” hotel, it’s a first-class dump: the lobby is OK, but the rooms are pretty Spartan (but clean). You don’t normally see corn being grown on the front lawn of your hotel, but the crop here extends right to the front door. There has already been a shortage of arable land in the north (the north half of the country is mountainous and was more industrial; South Korea ended up with most of the farmland) and every square inch is under cultivation. Still, North Korea cannot feed itself. During the famine in the 1990’s, an estimated one million people died, and only foreign aid staves off a recurrence. The situation is aggravated by low yields due to lack of chemical fertilizers, pesticides and farm machinery. Add to that unusually cold weather (hello, global warming). Here it is July, and the corn is barely to my knees. It’s going to be a hungry winter.

Just prior to dinner we visit an art exhibition. If you guessed that all the paintings are on a single theme, you would be wrong. There are several themes: The Great Leader, The Dear Leader, the army, agricultural production, industrial production, and tigers (no doubt metaphorical). After seeing so many depictions of The Dear Leader offering "on the spot guidance" in laboratory, factory, farm and field, I wonder why he hasn't yet invented the luggage ramp. which the hotels conspicuously lack.

Tuesday. Our last day in country. We drive to Sonbong, the neighboring, smaller sister city of Rajin. It, too, is a port, which we visit. There is a monument commemorating the visits of Kim Jong Suk, “mother of the nation,” who hailed from these parts. (She was the wife of Kim Il Sung and mother of Kim Jong Il.) Like every city in the DPRK, Sonbong boasts a Revolutionary Museum. When we enter the main hall Mr. Creepy snatches the hat off my head. Why? Because were approaching a portrait of the Great Leader. The pride of the museum is a set of tree trunks with anti-Japanese slogans carved on the trunks carefully preserved in humidity-controlled cases. Curiously, new ones bearing worshipful inscriptions to Kim Il Sung are being continually discovered, curious because at the time he was an unknown major in the Red Army stationed in Siberia (which is where Kim Jong Il was actually born). There are a dozen or more rooms devoted to the exploits and achievements of the Great Leader, but we are subjected to only two of them. Afterwards, Mr. Creepy goes around asking us if we agree that Kim Il Sung was the greatest person in history and what the people in our home countries think of Him. When he does not get the answers he expects, he seems completely befuddled.

After a last lunch, delicious seafood again, we drive to the railroad station near the border. There are lots of locals waiting for the train, but we are segregated in the VIP waiting room. The exit formalities begin. All our paperwork is in order. Luggage inspection is cursory. (What could we possibly smuggle out?) What they are really interested in is inspecting the photographs we have taken. Since everything is digital now, we have to scroll through our memory cards. They are looking for photos that show the country in an unflattering manner, but I think this exercise is mostly symbolic: no one is forced to delete more than one or two pictures. What are the offending images? Ox carts and old people. I lose one: a shot of a guy leading an oxcart down the main street in Ranjin. (In retrospect, I am certain it would have made the cover of National Geographic.) A couple in the group had the foresight to download their photos to their laptop and delete any questionable ones from the camera memory.

The train consists of two cars: one for Koreans and one for foreigners. With us are the Russian railway workers against whom we played soccer yesterday. Our mobile phones are returned and everyone frantically takes advantage of the signal from the Chinese network before we leave its coverage area. The Russians have a better idea: they break out the vodka.

It’s a very short train ride, just a few minutes: across the frontier and over the Tumen River to the Russian town of Khasan. Our guide, Julia, has come from Vladivostok to meet us. Just as well, because no one else speaks English. She has never been here in her life. The Russian border officials are quite surprised to see us. We are the first tourists ever to have come over from North Korea.

We drive for two hours to the seaside resort village of Andreevka, where plastic palm trees line the beach. (They insist that this is not Siberia, though the distinction may be too fine for us to draw.) We have advanced two time zones, so the sun more closely correlates with the clock. It is near the solstice and we are far north, so after a late dinner there is still daylight to look around. There are two well-stocked markets; in true Russian fashion, about half the shelf space is devoted to beer, wine, and liquor. An ATM gives us access to rubles.

Our activity the next day is a boat ride to Furugelma Island, almost all the way back to Korea. Formerly a defense installation, it is now a nature preserve. Getting there requires almost two hours on not very calm seas, but when we arrive we have the place to ourselves. We hike up into the hills amidst blooming wildflowers and abundant birdlife. There are soldiers’ graves, abandoned housing, and rusting guns overlooking scenic coves. Punctuated by a picnic lunch on the beach, the day passes quickly.

The following morning we leave at an ungodly hour and drive an hour to the town of Slavyanka where we board the 6:30 AM ferry to cross the Amur Bay to Vladivostok, Russia’s only ice-free Pacific port and home to its Pacific fleet. As we enter the harbor we pass several moored icebreakers and numerous naval vessels. During the Soviet era the city was closed to foreigners.

It is still early as we board our bus and start our tour. Geographically, the city resembles San Francisco, situated on hills at the end of a peninsula. Although the city is small and compact, getting around on the bus is slow going because the streets were not designed to handle the current crush of private vehicles. Interestingly, although in Russia they drive on the right, almost all the cars have steering wheels on the “wrong” side. That is because they are from the streets of Japan, where strict inspection laws effectively force the retirement of cars more than a few years old. Regular ferry service across the Sea of Japan keeps the used car supply replenished.

Our first stop is the Eagle’s Nest, a hilltop viewpoint overlooking the city below. There is a funicular railway (the only one in Russia), but we drive. Then, back to the embankment for a quick look at the war memorial and the triumphal arch commemorating the visit of the Tsarevich Nicholas in 1891 and a tour of submarine C-56, a WWII boat turned naval museum. In 1942-43 it crossed the Pacific and transited the Panama Canal to join the Northern fleet. It didn’t actually sink anything; its principal accomplishment was not getting sunk itself, for which it was awarded a Red Banner.

The main street, Svetlanskaya, used to be called Lenin Street. His statue still stands across from the railroad station, the terminus of the trans-Siberian railroad. Completed in 1903, it departs three times a week on the six-day journey to Moscow; arrivals are on alternate days. The ornate station and its murals have been restored. Outside there is a US locomotive, commemorating US aid during The Great Patriotic War (WWII), and an elaborate marker for kilometer 9288, the distance from Moscow.

After Port Arthur fell in the Russo-Japanese war (1904-05), Russia spent vast sums to make sure a similar fate did not befall Vladivostok, its sole remaining year-round port. In the afternoon we drive to Fort 7, one of sixteen built to protect the city. With concrete walls up to eleven and a half feet thick, it was a Pacific Maginot Line, impregnable but never tested in battle. The big guns are gone and the fortifications abandoned, but it’s still both impressive and spooky.

Dinner is at a restaurant named “Nostalgia.” It’s a tourist place with menus in English, but the food is good. The décor includes portraits of the Romanovs and White Russian generals, but I don’t think that many locals long for the tsarist days. A more authentic nostalgia can be observed in a nearby downscale cafeteria decorated with a huge map showing the vast reaches of the Soviet empire in a single color simply labeled “C.C.C.P.”

Vladivostok is an anomaly: a Slavic island in an Asiatic sea. I was expecting a mix of Europeans, Siberians, Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, and assorted others, but uh-uh, it’s Slav City. The only orientals I see are the Chinese tourists in our hotel. To underscore the point, almost all the local gals are blond or bleach their hair that way. They are strikingly good-looking: tall, thin, and dressed in tight clothes, short skirts and high heels.

We are staying at the Hotel Vladivostok, a concrete hulk that in commie times was operated by Intourist as the hotel for foreigners. Typical of those relics, it’s utilitarian but well located. Chiefly for lack of alternatives, it continues to capture the tour group trade (nowadays mostly Chinese). Renovation of the rooms has been haphazard, but at least there is wifi. Adjacent to the hotel is a gentlemen’s club, cover charge $50.

The next day is a free day. My first stop is the museum to see the stuffed Siberian tiger battling a stuffed bear. It is the acme of both poor taste and the taxidermist’s art. It is roped off, so the idea is to sneak up as close as possible to pose for a photo until the lady notices and yells at you. There are three floors of other exhibits, but after the tiger and bear it’s all anti-climactic.

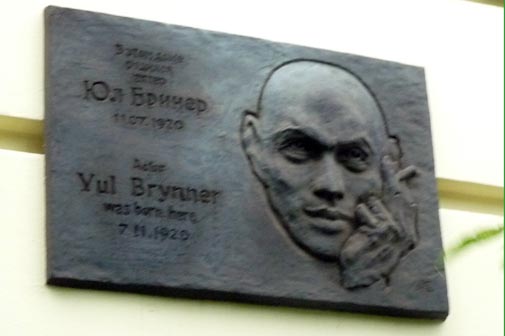

Next door is the house where Yul Brynner was born in 1920. It’s a substantial dwelling (his family was well to do and fled after the Revolution). On the other side are the two Stalin-era apartment buildings where high party officials resided.

The Lenin statue is relatively modest, but not so the Monument to the Fighters for the Soviet Power in the Far East. In the years following the Bolshevik Revolution this region was controlled by the Whites. The arrival of the Red Army in 1922 marked the end of the Russian Civil War. The Monument is more an expression of triumphalism than a war memorial.

There are no Scottish restaurants here; the local place of renown is Magic Burger. Disparaging words from our leader are insufficient to deter me from an authentic Vladivostok culinary experience. The eponymous product is pre-made and wrapped in saran wrap. When you place your order they microwave it in front of you, leaving the wrapping on to fully infuse it with that rich plastic flavor. When done, it looks and tastes like a meatball that’s been stepped on. Yet customers are lined up out the door.

Two days in Vladivostok is just about right. While most of the group attends an evening soccer match (in which I can’t even feign interest) I spend the time up catching up on the web. We have just emerged from internet-free North Korea and I will soon be once again behind the Great Firewall of China.

We have to leave the hotel at a ridiculous hour for our early morning flight back to Beijing (“Peking” in Russian, and, for that matter, every language except English). The Soviets liked to build airports an hour distant from town even though there is nothing in between.

We travel on Vladivostok Air, which gives me my first experience in a non-vintage Russian aircraft. The modern Tupelov they fly is comparable to Airbus and Boeing products. Beijing is 800 miles and three times zones away, meaning we arrive an hour before we depart.

I have another ten days before my flight home. If I had my druthers I would be moving on the same day, but it’s not so easy to get a train ticket, particularly on weekends. There are something like seventeen trains a day to Inner Mongolia, but the next available is noon the next day. Even then, the only “seat” I can get is a sleeper berth, available because Chinese are reluctant to pay the extra cost for a non-overnight trip. The journey is about ten hours.

A few hours from Beijing the Blade Runner weather ends. Instead of rainy and hazy it becomes sunny and clear. The terrain is rolling hills, sparsely populated. Sharing my compartment are an engineering student who speaks a bit of English and translates for the others, a Mongolian woman, and a Chinese guy. All think that I am the most exotic person they have ever met. I am the only big nose on the train. Little kids point and stare.

Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, was, until recently, a small Mongolian city, but it has undergone breakneck expansion and is now a medium-size Chinese city, i.e., the population of a small nation. Huge apartment blocks and shopping malls are under construction everywhere.

I arrive at night and check into my hotel, where there is ample proof that Chinglish is alive and well. On the back of my room door: ”Please don't worry if a fire is occuring we hotel have owned succor scattering facilities to sure you transmit safely. Point profess your excellency seat.” At least have some idea what they are talking about; often, if you don’t know the subject, the message is a complete mystery.

The next day I set to see the sights of old Hohhot. First stop is the Dazhao temple complex, home to the Tibetan lama community. There are close religious ties between Mongolia and Tibet, and the head lama here is considered a living Buddha. There are more Buddha statues than lamas -- the prayer halls contain only a token few monks chanting. I guess these days people prefer seeking riches rather than enlightenment. Because this place is not on the standard tour bus itinerary, I am pretty much the only visitor.

In contrast, the parking lot at the Xilituzhao temple complex across the street is packed with tour buses, and a hefty admission is charged (the other one is free). I don’t know why there are two separate temples, but this one seems more Chinese. It’s been renovated with bright, garish (but probably authentic) paint and gold leaf.

Still another temple is Wu Ta, or the Five Pagoda Temple, built in distinctly Indian style. It’s small but elegant. On the walls are more than 1500 carvings of Buddha, all different.

Finally, there is the Great Mosque, notable for its fusion of both Chinese and Arab architectural style.

I get all these done on Monday. On Tuesday morning the eye-popping new Inner Mongolia Museum reopens. It is state of art in its displays, but lacks tigers fighting bears.

The first hall I visit is “Underground Treasures.” Lip service is paid to the “friend of the earth” and “harmonious development” mantras, but the real message is “Inner Mongolia has loads of mineral resources and we’re going to exploit them. As a sop to the people whose land is being raped, the captions are in Mongolian as well as Chinese and English.

China’s space program is based hereabouts, and the next gallery is devoted to rockets and cosmonauts. Did you know that the local herdsmen were proud to surrender tens of thousands of square miles of their grazing lands to help contribute to the development of China’s national defense system?

There are numerous galleries devoted to arts and artifacts, with special attention to local hero Genghis Kahn and his band of merry Mongols.

And who doesn’t like dinosaurs! Huge skeletons are regularly found in the Gobi Desert, so it’s dinos galore.

The big thing to do when visiting Inner Mongolia is a grasslands tour with overnight in a ger (yurt in Turkish), but I’ve already had my ger experiences (in (Outer) Mongolia, Uzbekistan, and Krygyzstan) and am limited on time, so I decide to move on. I get a sleeper berth on the afternoon train to Pingyao, ten hours or so south.

When reach Pingyao well after midnight, I am the only one to get off the train. Despite the hour, the station is fully staffed: a ticket checker to check my ticket, guards who won’t let me leave through the entrance door, and a ticket seller who won’t sell me any tickets (all my choices are coming up “not available”), I disappoint the waiting taxi drivers by walking across the street to the hotel facing the station, where the entire staff is roused from slumber to check me in.

It’s goodbye to the clear, blue skies of Mongolia and hello to the gray haze that blankets industrial China. Pingyao, a well-preserved Ming walled city, would be very photogenic if you could see more than ten yards. Even the pictures in the guidebooks look like they were taken in heavy fog.

My hotel lacks wifi as well as character, so the next day I move to a guesthouse in the old city that has both. For transport I rent an electric bicycle. Boy, this sure beats pedaling! With it, I tirelessly cruise the streets of the old town otherwise closed off to vehicular traffic. The old city is devoted to tourism and this place is very popular with Chinese tourists, but western visitors are mostly the backpacker set. The ambience is great, but I don’t bother with the 140 yuan ($21) ticket needed to gain entry to the dozens of museums – to me, one Ming interior is pretty much the same as the next.

My powered chariot effortlessly takes me the three miles south to Shaulin Si, a temple famous for its Buddhist carvings so lifelike that they are kept in cages. (Either that, or you are not supposed to touch them.) The dinginess of the buildings and interiors makes one appreciate the value of a coat of paint. Another misplaced World Heritage designation.

I sign up for a day trip to two area attractions. The first is the Wang Family Courtyard, a walled village built around 1800 by wealthy merchant brothers. The buildings and decoration are very ornate but all dun colored, making for boring photographs. My theory: the compound was designed prior to color photography -- for the monochromatic real estates brochures of the time, paint would have an unnecessary expense. With no architectural variety, it’s a Qing-era Levittown.

The Courtyard (actually, there are 35 courtyards within) is now entirely a museum. Half the buildings are occupied by souvenir shops. They are filled with the tacky stuff the Chinese buy, not the truly glorious kitsch that interests me. There is English signage identifying the Honesty Room, the Moral Character Room, the Good Fortune Residence, the Residence of Examples, The Lasting Culture House, and so forth, but nothing that answer my question: what happened to the Wangs? Were they executed by Mao as class enemies?

The menu at lunch includes sparrow, “oild boar,” and “wild-eaten hens egg.” I stick to comestibles that I can more or less recognize.

In the afternoon we visit the Zhang Bi Underground Castle, a 1500 year old complex of military tunnels that lies beneath Zhang Bi village in a layout that carefully corresponds to the zodiac. The full extent is six miles, although only about a mile is now open to visitors. There are three levels of tunnels up to 60 ft deep with offices, meeting rooms, horse stables, communication tubes, booby traps and other defensive measures. There is no evidence that it was ever actually used in wartime until the Japanese occupation in the 20th century.

I am improving my travel plan on the fly based on the availability of train tickets. No luck in getting anything traveling in the direction of Shanghai, where I need to end up, so I book a sleeper to Luoyang, site of the Longmen caves.

To quote from the UNESCO World Heritage designation: “The grottoes and niches of Longmen contain the largest and most impressive collection of Chinese art of the late Northern Wei and Tang Dynasties (316-907). These works, entirely devoted to the Buddhist religion, represent the high point of Chinese stone carving.”

I check into a hotel across from the train station and grab a bus to the caves. There are, according to the guidebook, 2300 caves and niches and over 100,000 Buddha figures carved into the cliffs on either side of the Yi River. They are indeed impressive, as is the admission price, 120 yuan ($18), a huge sum by local standards. The site is built for Chinese-style tourism: to get from the parking lot/drop-off to the actual entrance you must walk through a half-mile of souvenir stands. Ahead are construction cranes – are they building new grottoes to meet the demand?

The other regional tourist draw is Shaolin monastery, home to the original Kung Fu masters. It’s a couple of hours away and considered a tourist trap even by Chinese standards, so I don’t. I need to be getting to Shanghai. The trains are all sold out, so I take a bus to the provincial capital of Zengzhou and, from there, a sleeper bus. The roads are good, but the journey is not as comfortable as a train. I arrive in Shanghai the next morning.

I’ve been here many times before, but I’m back for a look at Expo 2010. Due to the fair, all the reasonably-priced hotel rooms are long since gone, so it costs me a budget-busting $60/night for a decent place. I figure that today, Sunday, is probably the most crowded, so I wait until evening for the crowds to thin and the admission prices to halve. According to the official website, so far today, as of 2:30 PM, 426,000 visitors have come through the turnstiles.

The Exposition site is on both banks of the Huang Po River. Interestingly, it has been overlaid on to the existing urban footprint of regular streets with multiple entrances on the periphery – the one I choose is a clearing in the middle of fenced-off apartment buildings and retail stores.

One side of the river has corporate governmental entities exhibitions. The international pavilions are on the far side. There are long lines at all times for the most popular, but in the evening one can stroll right into the minor ones. The first pavilion I enter is Turkmenistan’s, which I commend for its excellent air conditioning. (Whoever thought of having a worlds fair here in the summertime had rocks in his head.) Iran’s is all about medical technology, pharmaceutical production, and high tech manufacturing; nothing about nuclear bombs. Not surprisingly, in Palestine’s you don’t see anything on suicide bombers and sending all the Jews back to Europe, but a whole lot about its capital, Jerusalem, “the city of peace.” Their view of a peaceful future can be in the scale model of the city -- the Wailing Wall is nowhere to be found.

After dark the fair becomes a visual treat. The Chinese are really into colored lights, and the illumination alone is worth the price of admission. I only make it about halfway across the Expo grounds before closing time.

I return the next day for the full day. The entry gate, where all visitors undergo airport-level security inspection, is only operating at about 5% of capacity, but there is no wait. Inside, it doesn’t at seem at all crowded, but that doesn’t mean no queues. The PA system gives frequent updates on waiting times: 6 hours for Saudi Arabia and Germany; 5 hours for Japan and Korea. The countdown by country continues until, below 3 hours, they don’t even bother. There are long lines at pretty much all the western countries. (Last night, near closing time, I was able to enter Australia and New Zealand without waiting.) Having already been to “the real thing,” I don’t visit anyplace with more than a three-minute wait time.

But for the vast majority of visitors, i.e., Chinese provincials, this is as close to foreign travel as they will ever get. At each pavilion you can get your “passport” stamped; there are 190 countries represented, and some people seem to be trying to collect them all. The country count is high because many smaller states that can’t afford a separate building are grouped together by region in large exhibition halls.

Every bit of construction is new but, aside from a few that are architectural statements, most are gussied-up generic buildings that will probably be turned into space for trade shows and conventions. Inside, one finds displays of the type that the economic development authority puts up in the airport. Thus, Togo, a small blotch on the African map with barely a functioning railroad, unashamedly exhibits artists’ renderings of bullet trains with “Togo” penciled on the locomotives.

In some pavilions half of the floor space is devoted to gift and souvenir shops. I think they are supposed to feature items from the home country, but there seems to be an awful lot of cheap Chinese jewelry. Some places price their stuff to sell; others seemingly want to make sure they will never need to restock. Cuba is selling cigars at $25-50 each (at those prices, they'd better be real) and overpriced rum drinks. Indonesia has a coffee bar where you can buy a cup made from beans shat out by a civet cat for $40 – due to limited supply (and an exhausted civet cat), they prepare a maximum of twelve cups per day.

But in general, visitors are not gouged. Admission for a single day is $27, and there are all sorts of discounts. There are convenience stores and fast food outlets. Sodas are under 50¢/can; drinking water is free and ubiquitous. National pavilions have restaurants and cafes, but the prices at those venues apparently include airfare to Shanghai for the chef and his entire staff.

As the day progresses, I come to the conclusion that poor countries are full of smiling, attractive young women in colorful costumes and the richer ones are populated by ugly people and minorities. Another rule of thumb: the crappier the country, the hotter the babes but the lousier the air conditioning (middle-east counties excepted from both halves of this last rule.)

|

Oh and there’s the entertainment. Who doesn’t like Polynesian dancers in plastic grass skirts and coconut shell bras? No one, me included! The Chinese especially appreciate one full-figured gal with an ample posterior and the ability to rotate it like a paint-shaker.

|

|

By evening I’ve had my fill. Back to the hotel and my flights home tomorrow. I have a twelve-month multiple-entry visa for China, so, like Ah-nuld, I’ll be back.