The Long Train Ride

I have been planning this trip for a long time: Amsterdam to Hong Kong by Rail. What I have not planned for is a hurricane. The day of my departure is the even of the expected arrival of Hurricane Floyd. Jacksonville is gripped by anticipatory panic: downtown is shut up tight, commerce has been suspended, and huge traffic jams clog all routes inland. I am supposed to take off at 5:00 p.m. Commercial aviation has already been suspended in South Florida but my flight is still on the board.

As I leave home the sky is turning ominous. At the airport, some 25 miles northwest, the skies are still sunny though the wind is picking up. The terminal is eerily deserted. All flights have been cancelled save for three; mine is one of them. Many no-shows on what was a fully booked flight. The girl next to me volunteers that she spent over $1,000 for her ticket (actually, her company did), more than I am paying for airfare traveling around the world; I feel suitably smug.

We arrive at the newly-completed Terminal C in Newark. I think we have landed in Madrid, because all the signage is in Spanish.

The next leg is to Amsterdam on an ancient DC-10. It is off-season, and there is plenty of room. The airlines have abandoned trying to cultivate an illustion that transoceanic flight is a grand experience. No more menus to help you determine whether you are eating chicken or fish, and they don’t even tell that the booze is free. Movie: Shakespeare in Love. Already seen it.

Schiphol airport is predictably unexciting and efficient. The train platforms are right beneath the terminal and but an escalator ride away. I buy a ticket to Warsaw with an overnight stop in Berlin.

To my amazement, it takes hours for the train to reach the German border. The route runs to Maasricht at the extreme southeast corner of the country, almost the maximum possible distance one can travel within Holland.

The German trains, as one might expect, are perfect: completely clean, and nothing out of order. Unless you look out the window, you can't even tell that you are moving, and if you do the passing scenery is just a blur. No clickity-clack, rocking, noise or vibration. I share a compartment with a wacky old Dutch lady and her dog Cesar.

The ride to Berlin takes about seven hours. We pass through West Berlin, then the no-man’s land where the wall was and that is now the world's largest construction project, and end at the Ostbahnhof, the main train station for what East Berlin. My theory is that it should to be easier to find a cheap place to stay in the poor half and that eastward trains would originate here. When we pull into the station at 9:30 p.m., it is deserted. There is nobody here or in the sturrounding streets. There is no commercial activity of any sort and no hotels. I stow my luggage in a coin locker and take a local train back west to the Zoo station. What a contrast! The station and the surrounding area is a riot of neon and activity. I quickly locate digs for the night.

I oversleep, waking up but twenty minutes before my train to Warsaw is due to depart from the Ostbahnhof. I race out the door to the Zoo station and find the train sitting there, ready to depart. It turns out that all trains go to both stations and that the east station is now but a brief stop, where I will have all of six minutes to find and retrieve my luggage. I fly down the stairs from the platform and am relieved to see that of the many locker banks scattered throughout the station, mine is right there. I make it back with two minutes to spare.

The trip to Warsaw is uneventful. En route I chat with an East German businessman who, because he speaks no English, is at a considerable disadvantage in reunified Germany. Not much call for Russian these days.

At the station I meet up with Jade, a gal from Singapore who will be my travel companion. (I had put up a posting on an internet travel board and she responded.) She has had her own adventures en route from Singapore by way of Moscow.

The old city in Warsaw was reduced to rubble in 1944. Nothing stood over waist high. It has been completely rebuilt from old photographs and paintings. Although the facades and roof lines are old-looking, the interiors are modern, which is a big help in the plumbing and electricity department. Interestingly, a line of "old" houses from the front is actually a single building once you get inside. The city has lots of WWII monuments, most very large, modern, abstract, and ugly. Not a trace remains of the ghetto, which was completely leveled in 1943 -- its former area is filled with modern apartment blocks. There is a memorial at the center, but I don't think the Poles are all that regretful: I am sure they appreciate the flats more than they miss the Jews.

Finding a place to stay proves to be a problem. In the communist era there weren’t many tourists or business travelers, and new construction is all high-end. I have a list of hotels but find that there is no room at the inn, any inn. After making about 40 telephone calls, the accommodations desk at the visitors bureau finally locates a room: a former workers' dormitory now converted to a hotel (not again!) catering to budget Russian travelers. At least it only costs $22.

I had figured on having the first afternoon in Warsaw as well as the next morning before boarding the Baltic Express from Warsaw to Tallinn. To my surprise, the train stopped running two years ago. (Thank you, Lonely Planet, 1999 edition). As subsidies disappear, rail service is dwindling. What remains of it is a train to Riga via Vilnius at 9:00 AM. It is still cheap though: $16. (Actually, there are numerous trains to Vilnius but they all cut through a corner of Belarus, which requires a visa. This train goes around Belarus.) This truncates our visit to Warsaw. Just as well -- in the morning it's raining.

The train takes all day, but not because the distance is so far. I estimate we're moving at about 35mph. It is slow, clickity-clack ride. We reached the border at about 3:00 p.m., where it is necessary to change trains because Lithuania, like the rest of the former Soviet empire, uses Russian gauge track, which is a few inches wider than standard gauge. The train consists of two cars, one first class and another second. The only passengers are foreigners detouring around Belarus.

Another surprise: Jade is pulled from the train because she does not have a Lithuanian visa. (I don't need one.) They issue visas on arrival only at the airport, not at land crossings. Luckily, her Russian visa enables entry the next day. (Mine is not valid for another three days. She will travel back to Warsaw, fly on to St. Petersburg and meet up with me again (we hope).

On the ride to Vilnius I chat with an Englishman who owns a pub in Cambridge. He rode teh reverse route of ours, from Peking to Moscow, in 1967, one of the last tourists allowed in China as the Cultural Revolution roiled that land. He is traveling light: just a small tote bag, a start contrast to my 60 lbs of stuff (mostly junk food). Next year he is planning to travel from London to New Delhi by train.

The train arrives in Vilnius about 8:00 PM. I inquire about trains onward and find out there is only one, a continuation of the train from Warsaw with sleeper cars are added. I decided to catch tomorrow's, which gives me 24 hours in Vilnius. After all, it is the "next Krakow" (which is, in turn, the "next Prague"). After subsisting on peanuts and snack food all day, I do not want to wait for slow food. There is a McD's across from the station, where I learned that in the Lithuanian language the word "hamburger" is a registered trademark of the McDonald's Corporation.

Vilnius is a lovely city. Not much developed in peace nor much destroyed in war. The Litvaks HATE the Russians and have done a thorough job of eradicating all traces of Soviet rule. The Museum of Atheism is once again the cathedral. . The eponymous statue is missing from the former Lenin Square, but I do find a monument to Frank Zappa.

Directly opposite Lenin's statute stood KGB headquarters, now the Museum of the Genocide of the Lithuanian People. It is as it was when the commies fled in 1989. Former inmates are the guides. The torture chambers are intact. Signs explaining their operation note what "improvements" were made in the 1970's and 1980's. Sacks of shredded documents are still piled up. It is much more chilling in Auschwitz: it all took place a mere ten years ago, and, while the Nazis are either dead or consigned to the lunatic fringe, these perpetrators are still at large and their apologists in the White House.

The city offers lots of interesting stuff to see on uncrowded streets. There are few other tourists, and no tourist hassle. When I walk into the market, my obvious tourist status doesn't deter the merchants from importuning me to buy slabs of flesh and various animal parts. I drop in on a Russian orthodox church service; in the center of the sanctuary three mummified saints repose in a glass case.

I take dinner at a Hungarian restaurant (why not?) before boarding the night train to Riga. After very comfortable trip (first class sleeper, $15, matresses, linen, pillows, etc.), we arrive at 6:15 a.m. in Riga, the capital of Latvia, where I make an unsettling discovery: there is no longer any rail service between Riga and Estonia. The purity of my journey has been compromised! I will need to make the next leg of my trip by bus. The Soviet rail network was designed to connect the satellite countries to Russia not with each other. There are still trains directly to Russia, but, like in the U.S., the advent of modern highways (post-Soviet) has killed the many lesser train routes. Unfortunately, there is no time to see Riga and still make it to St. Petersburg on time.

Tallinn is even prettier than Vilnius. Its old city is medieval and completely intact: cobblestone streets, old buildings, castles, every corner a postcard view, one of those UN World Heritage deals. (In contrast, Riga was pretty well flattened in the war and was rebuilt as a modern port.) The streets are crawling with Finns who come over on the fast ferry for a weekend of cheap boozing.

I spend the afternoon wandering around and pretty much see everything. The pedestrian/tourist congestion diminishes hourly as Sunday afternoon progresses and the army of Finns return to their ferries home. Having been warned by my guidebook that traditional Estonian food consists of jellied meat, fatty sauerkraut, and herring rolls, I eschew the local cuisine in favor of Estonia's first and only Hawaiian restaurant. It’s very good, although I don't think King Kamehameha would have recognized anything on the menu.

Another sleeper train takes me to St. Petersburg. My first class compartment is big enough for ballroom dancing; bigger than some hotel rooms I've stayed in. At 3 AM my slumber is disturbed when I am rousted by the Russian border guards. First, they carefully inspect every nook and cranny of the compartment for stowaways. (Who would want to sneak INTO Russia?) They stamp my customs declaration, then, just to remind me who is in charge, rifle through my luggage anyway. Welcome to Russia.

We arrive in St. Petersburg (f/k/a Leningrad, f/k/a Petrograd, f/k/a St. Petersburg) early Monday morning. Jade is waiting for me on the platform (clever girl).

We are transported to our accommodations. Rather than a dreary Soviet-style hotel, we have selected a "family stay." That means living Russian-style with a host family. Their apartment is among the blocks of highrises that were thrown up in the late Soviet era. We are on the Gulf of Finland and a stones throw from the Pribaltiskaya, the hotel where I stayed in 1985.

The interiors of the individual apartment units are quite nice, but but the entrance, lobby, and elevator are straight out of the South Bronx. Judging from how people treat communal property, I would say that 70 years of brainwashing didn't take.

We head out sightseeing. Boy, have things changed! The Nevsky Proskect, one of the grand boulevards of the world, was previously notable for magnificant buildings and an absence of commerce. Hordes of pedestrians strolled, unable to spend a kopeck. These days, it's all upscale shopping. Formerly empty storefronts are now filled with imported goods that ordinary Russians cannot afford. There used to be no billboards or advertising save slogans such as "The Communist Party Is The Vanguard Of The People" and "Strive To Fulfill And Surpass The Plan," but now it seems that every square inch is occupied by commercial messages. Something else: parked right on the sidewalks are big, black, German cars belonging to Russian biznesmen (i.e, Mafia) guarded by big guys in black leather. Lots of beggers of all ages.

I stop at a bank to change money. The exchange teller takes my brand new $100 bill, looks at it closely, and tosses it back with a sniff as if to say "how dare you try to pass off this obvious counterfeit on me?" A money changing shop, although far seedier, is not so picky.

It used to be that admission to museums and historic sites was nominally only pennies, but the only way foreigners could go was by booking through Intourist, which charged big prices payable in dollars. They have cut out the charade: now, there are dual admission prices by which foreigners pay 15 or 20 times as much as Russians. It's annoying, but no more dishonest.

At least you can get lunch now. We stop at the Stroganoff Palace for (you guessed it) Beef Stroganoff. Price: 6 "currency units," an artifice which obviates the reprinting of menus as the ruble devalues. A currency unit is the ruble equivalent of one U.S. dollar at that day's exchange rate (although you still pay in rubles). But everyone still takes dollars. As the tour operator's brochure points out to its mostly non-American clientele: "No matter what you might think about the US and its role in the world, the population of the countries you are visiting think it’s a mighty fine place, and have no trouble with its culture, and in particularly its currency."

On the first day, we check out the usual sightseeing venues. Luckily, Jade has spent the previous day at the Hermitage, sparing me eight hours of looking at pictures. The next day we look for something different. My choice is real slice from the Soviet history cake: Kirov’s apartment. It’s now a museum to the Leningrad party leader assassinated in 1934. I don't think they get many visitors these days. The price on the admission ticket has been overprinted from 15 kopecks to 3 rubles, a twenty-fold increase but still only about 15¢ both before and after. My only complaint: no souvenirs for sale.

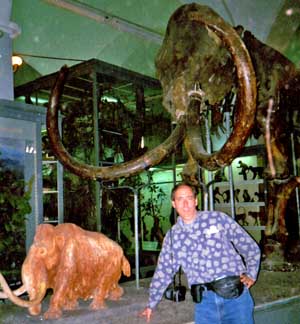

At the Natural History Museum we see a baby mammoth found frozen in the ice and the Kunstkammer, Peter the Great's collection of human freaks and other oddities. On the final day we go out to Peterhof, Peter the Great's summer palace modeled on Versailles, followed by a quick visit to the Hermitage. They haven't changed the pictures since last time I was there.

The ride to Moscow is on the famed Red Arrow, a sleeper train departing at 11:55 p.m. Since it is only an eight-hour trip, we slum it and go second class, four berths in a compartment. There are no stops, as the route was laid out by the tsar who drew a ruler line between Moscow and St. Petersburg, bypassing all other cities and towns.

Moscow too looks like a normal city: plenty of cars, neon, and billboards. In contrast to the bad old days when there were no consumer goods, now everything is for sale everywhere, although it appears that the much of economy has shifted to begging and to selling liquor (much of which is counterfeit or moonshine) from sidewalk kiosks every few yards. Vodka is literally cheaper than water: a half liter of the good stuff costs 39 rubles ($1.60), less than bottled water at the hotel. Marlboros are $1/pack. I don't smoke, but at these prices maybe I ought to start.

When we visit Red Square I finally get to see Comrade Lenin in all his pickled glory. No longer are there hours-long waits as the devoted line up to pay their respects; nowadays, it's tourists only. They keep threatening to bury him, but it hasn't happened yet. My complaint: no souvenirs for sale.

Jade wants to go to the Bolshoi ballet. Tourists tickets are plentiful at $50 and up. Our guide (our package includes a private guide in Moscow and St. Petersburg for a half day each) locates one from a street scalper for $4, still almost four times the face value. As for me, I pass on the opportunity to visit the world's largest McDonald's and instead embark on a fruitless search for an internet cafe.

The cool souvenirs are to be found in a flea market. Military headgear and nesting dolls galore! I buy a general's belt, a finely-machined stainless-steel vodka flask and various tchotckes.

OK, it's time to begin the trip for real. Saturday night we proceed to the station to board the Baikal Express. Moscow to Irkutsk, three days and four nights. We will be on the train until Wednesday morning.

The first class car is out of another era: heavy curtains, mirrors, pictures, sconces, and oriental rugs. There are eight compartments with two berths each, but only seven passengers total: me; Jade; 2 Brazilians; 2 Dutch; and 1 Swiss. No Russians except for the car attendant. It can be difficult to reserve first class because, in a nominally classless society, it was limited to party officials who needed more room to properly conduct The People's Business. As midnight approaches, our train chugs out into the darkness.

After a pleasant night's sleep, we settle into the rhythm of successive 23 hour days (we will be crossing five time zones). And rhythm there is -- the gentle rocking and clickity-clack of the rails will cure anyone’s insomnia. The weather outside is gloomy and but inside it is very comfortable. Each car has a large samovar with boiling water for tea, coffee, soup, or snacks. There is plenty of room to stretch out or wander around. In contrast with the "Con Air" experience of modern coach-class air transport, the train is a very civilized way to travel. Jade breaks out snacks she has brought from Singapore: seaweed-flavored peanuts. No, thank you.

I am too lazy to tour the entire train. From the platform, it looks about 15 cars long. There is one first class car, a few second class (four berths per compartment), a baggage car, a mail car, and a number of third class carriages. Those so not have individual compartments, but berths stacked racks like on a submarine. That is how the ordinary Russians travel; it’s too horrible to contemplate. (Think Dr. Zhivago)

The dining car is adjacent to ours. It doesn't get much business because the pool of potential diners is so small. (The Russians bring food or buy provisions from platform vendors.) The menu is handwritten and only in Russian, but that at least there is no separate price list for foreigners. The food is edible, though the portions are kind of small. (But at 31 rubles ($1.25), who can complain?) And though there are several selections listed, it doesn’t much matter what you order –- the waiter brings whatever the cook has decided to make.

We cross the Urals during Sunday night, so we don't get to see the pylon marking the division between Europe and Asia. By Monday morning we are in Siberia proper. Lots of birch trees, not much else.

Monday night we pass through Ekaterinberg. It's daylight when we pass through Perm, with its rail yard that is 135 tracks wide. There is a brief stop at Tyumen, the booming oil capital of western Siberia. During the Great Patriotic War (WWII) much of Russia's treasure was shipped east of the Urals, and Tyumen held the greatest treasure of them all: Lenin's corpse, secretly transported to the Agriculture Institute and tended by a team of specialists. The day passes pleasantly and unevenfully.

On Tuesday morning, September 28th, we awake and look outside. IT'S SNOWING! Certain people from the tropics, i.e. Singapore and Brazil, have never seen snow before and rush outside at the first stop. The falling flakes do not discourage the ice cream vendors on the platform. Somewhere out there is a pylon marking the halfway point to Beijing.

At various intermediate stops additional passengers join or leave the train. There not much air service in Siberia and the roads are terrible, so, for intercity travel, the train is the way to go. Russians with money join us up in first class. In contrast to the foreigners who keep our doors open and visit one another during the day, the Russians seal themselves in their compartments and watch videos.

|

|

The cities tick by. Omsk has a very nice station. Novosibirsk's is supposed to be even nicer, but we can't tell because it's dark. Especially impressive are the bridges that span the great rivers. At Novosibirsk is the mighty Ob river bridge. It took 94,000 workers three years to span the Yenisei at Krasnoyarsk. Between these cities are vast forests punctuated by an occasional village. Ohe last night we miss dinner. Although the train runs on Moscow time, the dining car runs on local time and has closed, our reckoning, in mid-afternoon.

Wednesday morning, we arrive in Irkutsk. I'm ready for another three days of train. Certain people from small islands in southeast Asia are not quite as enthusiastic.

We are met and whisked away to our homestay in the village of Listvankya on the shores of Lake Baikal. Our hostess is a genial lady and a fabulous cook. The house is sturdy and warm, but there is no indoor plumbing and no hot water. No showers for me for the next three days!

That afternoon we get a brief tour, including a visit to the Limnological Museum. The lake is the world’s deepest and holds something like 20% of the fresh water on the planet. Despite the best efforts of the Soviets to industrialize it's shore, the water is still pure and sweet and can be drank unfiltered.

When we arrive it is a beautiful Fall day. “Indian Summer,” we are told. (An interesting Siberian expression, no?) That night, winter arrives: the temperature plummets fifty degrees and when we wake up all the flowers, which had been in full bloom, are dead.

I want to go fishing. The guide has arranged a boat, which turns outs to be an enormous steel vessel powered by two huge diesel engines and with a crew of three. We are handed rods and reels heavy enough for giant marlin, and off we go. We ride out a short distance and head back to the shore, grounding the prow into the bank while the twin screws keep turning. They are churning up the bottom to attract the fish. I bait my hook and toss it into the roiling waters. A short time later I get a bite and haul out a slivery specimen about nine inches long. “Oh well.” I figure, “bait fish.” I take it off the hook and toss it back, at which point the crew explodes, “NYET! NYET!” That is, I learn, a grayling, what we are fishing for!

Over the next a couple of hours we catch a few more, then call it a day. It is overcast, windy, and freezing. The grayling are cooked up by our hostess and are delicious.

On the third day, we transfer to a homestay in the city of Irkukst. After having only outhouse in twenty-degree weather, I am ready for some indoor plumbing. Our new hosts are a middle-aged couple caught out of time. She is an economist. Of course, she was trained in Marxist economics, which these days is about as useful as being a witch doctor at the Mayo Clinic. He is a medical doctor employed by the state and thus earning just a few dollars a month. To make ends meet, they take in guests. Since their flat is so small, they give us the bedroom and he moves to their country cabin.

The city is interesting in that it is a historic Siberian outpost with a Soviet overlay. In the center of town are old buildings made of heavy logs next to concrete monstrosities. There is nothing special to see. After one night we resume our journey.

The classic trans-Siberian track runs east to Vladivostock, another three days away. We are taking the trans-Mongolian line south to Ulan Bator. (With this route we miss the world’s largest Lenin head in Ulan Ude.)

This particular train is operated by the Mongolian railways. They use the same East German cars, but there is a totally different ambiance. About 90% of the passengers are Mongolians returning from Moscow with consumer goods for resale; every compartment is crammed floor to ceiling with trade goods. Moreover, they are constantly shuttling back and forth exchanging items. It's like a line of ants carrying crumbs. You can't stand in the corridor without blocking the flow of commerce. And it's the same stuff that keeps getting shuttled back and forth. This has been going on for three days since the train left Moscow. We have to keep our compartment locked because people keep trying to get in to stow stuff in the lockers and above the ceiling panels.

At one of the final stops in Russia, we get off to try to spend some rubles. We are engrossed in a transaction when the clerk starts gesticulating loudly. We turn around and see that our train is leaving. We race down the platform and leap aboard the moving train, barely making it. Thereafter, we are gun-shy about getting off. When, at another station, we climb down to see a display of steam locomotives at the end of the platform, the train lurches and we immediately jump back on. (The train then sits idle for another 15 minutes.)

In the dining car, the fare is still Russian. At lunch, we order beef steak and beef stew with onions; we are served pork chops and mashed potatoes. That night, the menu in unchanged, but this time our order of beef steak results in some sort of minced meat.

The scenery changes from the dense Siberian taiga to vast, rolling steppes. Mongolia is big sky country. It is half the size of western Europe but has only two million people and even fewer trees. Ulan Bator is reputed to be the world's coldest capital. And we are approaching it on the world's coldest train. I guess they want to acclimate us because that night they don't turn on the heaters.

During the night we cross the border. Everyone has to fill out customs declarations. I wonder how the customs inspectors would treat the tons of goods being smuggled, but, apparently, they are in on the deal since no one pays any duty.

Again we are met and taken to a guest house in a converted apartment building and where hot water availability is largely aspirational. It’s a dump, but a tad better than the gers, (yurts in Turkish and English), circular tents that are the traditional Mongolian housing and are that found everywhere, even in the middle of the city.

Mongolia is no longer a Soviet client state. Lenin Avenue is now Genghis Khan Avenue, and the Lenin Museum has become a shopping center. In the center square is the obligatory Tomb Of The Pickled Commie. It's closed now, but I think he's still inside. Opposite the tomb is a giant equestrian statute of the guy looking like Genghis Khan. The Museum of the Revolution has morphed into the Museum of National History. Oddly, a museum dedicated to Marshal Zhukov, the Soviet WWII hero, still survives. We get a private tour. Who know how long it's been since anyone else has visited.

The Natural History Museum has a cool collection of dinosaur eggs from the Gobi Desert. The best attraction is Gandan monastery, which contains an enormous standing Buddha. You can have your photo taken in front of the facade and during processing an image of the Dalai Lama is superimposed. Little known fact: Mongolia used to have its own dalai lama who was recognized as an equal by the one in Lhasa.

A principal export of Mongolia are large, colorful postage stamps. But they are for collectors; you can't really use them. Here's how the scam works: new issues are sold at face value for a very short period of time; after that, they are only available in complete sets at a significant premium. Moreover, the individual stamps come only in high denominations or amounts unrelated to the cost of postage. And, until recently, you had to pay for them in dollars. Stamps for actual use as postage are small, drab and monochrome.

The next morning we are taken for our stay at a ger camp. It’s only about 30 miles from the city but it seems a million miles away. It’s in the middle of nowhere. Apart from barren hills, the landscape is featureless: nothing but earth and sky. There is no point in taking a walk since one place looks exactly like the next

For our afternoon ride they need to catch some horses. They are semi-wild, and have to be rounded up and driven into a corral. The scene is like a live version of a Marlboro ad except the horses are the size of ponies and the cowboys are wearing long robes and pointy hats and standing up in the stirrups. The slowest ones get caught and saddled. I get the first horse, which means the slowest. That's fine with me; one gal has the excitement of having her horse bolt with her on it.

All mounted up, we head out. We sit on leather "Russian" (English) saddles instead of wooden Mongolian saddles. Just as well, dem horses is bouncy! Our mounts being unresponsive to the reins, the ride is mostly of holding on tight while the Mongolian horsemen herd our group like cattle. I try to calculate long it would take to reach the gates of Vienna.

We ride to a real ger. It's not a whole lot different from the tourist version, except this one has a light and TV powered by a solar-charged battery. We are served refreshment: fermented mare's milk. It tastes pretty bad, but not quite as awful as it sounds. Afterwards, we head back. The process is the same, except this time we go FAST. It's pretty tiring, since we have to levitate like jockeys to keep from being pounded to death.

The tourist camp has is a central building with a dining hall and facilities with modern plumbing. Our ger has comfortable furniture, linoleum flooring, and a wood stove. That night I find out that the correct spelling of ger is C-O-L-D! When we return from dinner the stove has been fired up, and the tent is warm. After we have fallen asleep, the fire dies out. There is no more wood. As I shiver, I try to be thankful for small things: at least we had wood to burn; the authentic fuel to heat a ger is sheep dung.

After one night in camp we go back to Ulan Bator and spend last night is spent in a local hotel. That means one not built for western tourists. There has hot water, but it only dribbles from the showers. Our train to Beijing leaves the next morning.

The character a country is reflected in its trains. On Russian trains, the word is discipline; on Mongolian trains, chaos; and on the Chinese trains, order. This train is operated by the Chinese railways. The cars are spotless and new. We even have showers! This ride is a bit of a reunion as we are rejoined by various travelers we have met along the way. Eventually, everybody goes to Beijing.

Jade immediately proves her worth as a translator. Without her I would not be able to read and heed the placard in our compartment: "Please do not dismantle the fixtures." Nor would I know that bear meat is available from vendors on the platform.

We cross the southern Gobi desert. It is dry and sandy, but we don't see any dunes. Wild bactrians (two-humped camels) live out here, but they are few and far between, and they are too inconsiderate to pose by the railway tracks. I come up with a solution: just take a picture of the ubiquitous grazing horses and use Photoshop to add the humps.

Our entry into China occurs, in the middle of the night. Loudspeakers play jaunty music to welcome the train and the border post is festooned with Christmas decorations, but the inspectors are cheerless. I am stumped by the check-box choices on the immigration card for one's occupation. I can't really check off "farmer" or "worker." (What happened to "peasant?") I resist the temptation to write in "class enemy."

When the paperwork is complete, the train pulls into a giant shed where the cars are jacked up and the wheels changed from Russian gauge to standard gauge. It’s interesting to watch but Jade misses it because she has once again been removed from the train for questioning. This time, the problem is two small holes punched in the back cover of her passport. Six people from the train are detained, including one who doesn't sufficiently resemble his passport picture. After a purgative self-criticism session, five of the six (including Jade) are allowed to reboard.

As we move further south into China, the landscape gradually becomes less arid. Our route follows the Great Wall, although we catch only occasional glimpses of it. We don’t cross the wall (actually, we go under it through a tunnel) until we are close to Beijing. The closer we get to the capital, the heavier the pollution; the skies are dense and gray, and some factories are belching out bright orange smoke.

We arrive in Beijing is mid-afternoon. This is the end of the arranged tour. We are on our own. We have no hotel reservations. Once again, Jade to the rescue. She walks up to a hotel tout and starts jabbering away. Within minutes, we are escorted to a nearby three-star hotel, our first decent hotel since Moscow. The cost for a superior room: $32. (I had been unable to find anything for under $100 on the internet.) My only complaint: the shower head is mounted too low.

We are within walking distance of Tienanmen Square. On the way, Jade translates the political and moral exhortations posted about. We stop in a food store, past the live, wriggling, cicada larvae (yum yum!) to the meat counter where the choices include dog meat and donkey meat.

It is exactly one week since the 50th anniversary of the proclamation of the Peoples Republic. It was a major festive event for which the city has been spiffed up, with flowers planted, trash removed and beggars deported. The public was barred from the big parade, but the floats are now on display in the square, and it seems like all 10 million residents have come out to view them. They depict various aspects of economic and social progress and each province and region. The theme of the Tibet float is happiness at being part of the motherland; that of Taiwan's is a longing to rejoin. A giant countdown clock ticks off the seconds until the Portuguese quit Macau.

So infectious is the spirit of National Day that I buy a solid gold set of commemorative cards of "Three Great Leaders": Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin; #168 of a limited edition of 20,000, an heirloom for the ages. My enthusiasm has its limits as I pass on the companion set of the Ten Great Generals of the Long March.

If you can speak the lingo (or are with someone else who does) Beijing is a cheap place. Dinner for two at a great Vietnamese restaurant: $8.00. Bottle of local booze: 25 cents. (Yeah, it tastes like moonshine). Even the money is new and freshly printed for National Day.

It was too dark to take pictures of the floats, so we head out early Saturday morning for a photography session. Foiled again. As part of the continuing National Day celebrations the Square is closed for the Beijing Marathon and mass sport exercises. So, once again, I miss out on seeing the pickled Chairman Mao as well as the museum which shows how rampaging students attacked innocent soldiers in the 1989 “Tienanmen Incident.”

The marathon has created another crisis: it's time to go to the station, and the taxi drivers won't take us because the streets are closed. The metro doesn't go there. Jade to the rescue again: soon we are careening through the back streets on a bicycle rickshaw piled high with our luggage. It is quite a spectacle. Also death defying: because of the weight, we effectively have no brakes. We make it to the station just in time and are the last to board the train.

The Beijing - Hong Kong rail line is a $4.8 billion, modern high-speed direct link built for the return of the colony. Fast and quiet, is the flagship service of the state railways. We were unable to obtain tickets for the deluxe coach so we have to settle for soft sleeper. (Which would correspond to first and second class, if China weren't a classless society). But it is still very nice. We have the compartment to ourselves. I am the only devil (foreigner) in the car; the deluxe car next door is all devils. I count one deluxe car (16 berths), four soft sleepers (32 berths each), and nine hard sleeper (54 berths each). There are two attendants per car. Also, a non-stop loudspeaker with announcements in English and Chinese. After long lists of prohibited practices are recited, we are advised to report all infractions to the train police who will deal severely with "smuggling, sexploitation and other crimes." Apparently at a loss for material, they then start reading lengthy, detailed fare and tariff regulations.

The dining car has an interesting system: they come around to your compartment, take your order and your money, and give you a receipt and dining time. When you go to the car, your food is brought straight to you. Eliminates long waits for a seat. At lunch, I try the eel. Tastes like eel.

As we speed south, the polluted gray skies of Beijing give way to a rainy mist. (That reminds me, we've been traveling 3 l/2 weeks and haven't had any rain.) Jade entertains me by reading the signs along the way: "No strolling or picnicking on the tracks"; "Accidents from jumping on or off moving trains are the responsibility of you and your work unit"; "It is forbidden to lie down or sit on the tracks." The scenery is hazy, but excellent. I spend most of the time looking out the window. Between Ulan Bator and Beijing, I read a whole book. On this train I only get through twenty-four pages.

We go outside onto the platform at Guangzhou (Canton). The climate has changed from cool and dry to hot and humid. A bit further down we have to get off to go through immigration and customs even though we are still in China, When we return to the trains for the last stretch to Hong Kong, the car attendants have disappeared. I guess they aren't politically reliable.

Hong Kong, as always, is great. Shopping, eating, and gawking. Even during high season, the best hotel deals are not discoverable until arrival. We find a small, new hotel which is immaculate and decently located for half the best deal I could find on the internet. My only complaint: no foreign channels on the cable TV.

After an excellent trip, it's time to part company. Jade has a direct flight to Singapore. I am heading home via Tokyo and Dallas.

The flight home is predictably miserablel. At least it's a 777 with personal videos that allow channel surfing among several lousy choices. Also, because it's an American Airlines flight, slender oriental beauties have given way to battle-axes who can barely squeeze down the aisle. (Some of them are as old as me!) As I suffer the indiginities of coach class, I leaf through the inflight magazine, studying the world map and trying to decide where next to go.

Trip date: September - October 1999