Horn of Africa

Part II – Eritrea

|

|

To understand Eritrea you also need to know a bit of history. In the 1880’s the Italians colonized the Red Sea coast below Ethiopia and extended their domain into the adjoining highlands. The colony prospered under Mussolini, who poured resources into its development but also used as it a springboard for his invasion of Ethiopia in 1936. The Italian governate lasted until 1941 when they were defeated by the Brits. Postwar, Eritrea was annexed to Ethiopia as a consolation prize to Haile Selasse for the failure of the League of Nations to come to his aid. What followed was a thirty-year war culminating in international recognition of Eritrea as an independent county in 1991. The ensuing 26 years have not been peaceful.

|

|

The ethnic majority consists of Tigreans, who are indistinguishable from the Tigreans of Ethiopia. In ancient times the Kingdom of Aksum (Axum) encompassed northern Ethiopia and what is now Eritrea. The entire national identify can be summed up as “NOT ETHIOPIA! They exist in order to fight Ethiopia (and can't get along with their other neighbors, Djibouti and Sudan). To fight Ethiopia they need a strong military. To maintain a strong military they need soldiers and money. To get soldiers and money they need conscription and control of the economy. To prevent dissent they restrict movement and freedom. The result is a paranoid government determined to hold its people captive and desperate escapees seeking asylum in western countries.

Getting a tourist visa is not easy; the only sure way is to join a tour group, which is why our group is full. It’s a well-traveled lot: most have been to 100+ countries and for one guy this marks the final entry in his every-country-in-the-world tally.

The flight from Dubai lands at Asmara, the capital. The duty-free shop is the first of many strange sights: in addition to the usual booze and cigarettes, there is an entire wall of beer and display cases of laundry detergent and ordinary household cleaning products.

|

|

|

|

|

It takes a while to sort things out for everybody on arrival so we hang out at the airport café. This is not a throw-away economy: before we can leave all empty beer bottles have to be surrendered and accounted for, a ritual that is repeated several times a day for the duration of the trip.

The airport is only about two miles from the center of the city. What a contrast to Hargeisa! Asmara was going to be the city of the future. Young Italian architects designed bold and beautiful edifices in the then-modern art deco style. The city is their monument. (It was just listed as a World Heritage site.)

|

|

|

|

|

In addition to being a beautiful city, Asmara also boast a very pleasant climate. It is at 8500’ altitude, giving warm, sunny, dry days and cool nights.

|

|

|

|

|

Our base is the Ambassador hotel, a 1970’s pile that is located in the center of the city right on the main street. Electricity to the hotel and all of central Asmara is cut off from about 6AM to 2PM. Even when the electricity is on, one does not want to take his chances with the elevator that has probably gone 40 years without maintenance. The climb to my room on the 5th floor at that altitude is not something I want to do more than absolutely necessary. After reaching my room I can hear through the door the others huffing and wheezing as they ascend to still higher floors.

Directly across the street is the Catholic cathedral. In close proximity to its bell tower are the spires of St. Mary's Eritrean Orthodox cathedral and the Great Mosque.

|

|

|

|

|

A tourist visa allows one to visit only Asmara and the coastal city of Massawa – anywhere else requires special permission. And not all of Asmara is open: our guides have spent the morning obtaining permits to visit the city's tank graveyard.

|

|

|

It is an urban scrapyard of military detritus: tanks planes, trucks, APCs, etc. left over from the long conflict. As the Eritrean rebels did not have any heavy equipment other than captured pieces, what we are seeing are Ethiopian losses.

|

|

|

Two things are apparent: there is no steel mill in the country that could utilize all that metal; and someone went through a lot of trouble to gather this stuff up and drag it here. It probably would have been less effort to haul it to Massawa and load it on a scrap ship to China.

|

|

|

Afterwards we visit the Italian cemetery. Some of the family tombs are substantial, other graves more simple. It is still in use although the names on the more recent headstones are Eritrean not Italian.

|

|

|

We attempt to visit the former Kagnew Station ,a US Army base that served as an antenna farm/ listening post from 1941 to 1977. Not surprisingly, we are turned away.

|

|

|

Two nights before Independence Day there is a parade down the main street with floats and bands that passes right beneath my hotel room window. People begin gathering on the steps of the cathedral hours beforehand. (Unfortunately, it was too dark for photos of the parade).

The streets are decked out in flags and bunting. Repressive government nothwithstanding, the patriotism is genuine. The next night there is live music and dancing in the streets capped off by a fireworks display at midnight. Last year, the 25th anniversary of independence, was the big blowout, but this year's show is still pretty good.

|

|

|

The main festivities on Independence Day take place in the national stadium. Our tickets get us seated right behind a row of old men, who I assume are war veterans. After a droning speech by El Presidente, the show gets under way. It is a combination of marching military, Mig-29 flybys, reentactments of victorious battles, pop festival, and pep rally. The opposite bleachers are filled with placard-wielding students performing card stunts. All-in-all it is very much like a smaller-scale version of the mass games staged by North Korea.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The next day we decamp from our highland Asmara base to descend to sea level to visit Massawa. The road is good but very winding: it takes 3 hours to cover the 70 mile distance (only 41 miles as the crow flies!).

|

|

Massawa used to be called the Pearl of the Red Sea. Nowadays, it’s more like Aleppo-by-the Sea. The old city sustained heavy damage in the late days of the war, and almost nothing in has been rebuilt. The port is active but lethargic: were the government less bellicose, it could again be a seaport for Ethiopia, a country of 100 million with a thriving economy; instead, it is the port for a country of 5 million with an almost non-existant economy.

|

|

|

And it is HOT. Under the blazing sun, there is little sign of life. Once darkness falls and the temperature drops (a bit), shops, bars, and cafes show signs of life amidst the ruins.

|

|

|

|

|

The Dahlek Islands are renowned for snorkeling and diving, but we cannot get permits to visit them; instead, we are limited to Green Island, which is basically a sandbar opposite the city. It is clean enough, but the dustlike sand suspended in the water makes for poor visibility. Also, the water is very shallow -- no matter how far out you walk, it will not reach your waist. The Red Sea water temperature is very pleasant, not as warm as the Gulf of Aden at Berbera.

|

|

|

At the entrance to the city is the tank monument. Massawa was the site of the final major battle and a decisive victory for the rebels. They captured the city and port, but reprisal bombing by Ethiopia reduced the central area to its current condition. Three of the "victorious" tanks, previously captured from the Ethiopian army, are proudly displayed on pedestals; a closer look reveals that they fell victim to Ethiopian armor-piercing anti-tank weapons and probably were of little value in the assault on Massawa.

|

|

|

We overnight in Massawa (blissfully, the hotel has semi-functioning AC), returning to Asmara the next day, Saturday, a good day to visit the main market.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturday is also a big day for weddings. (And for reenacting the Abbey Road album cover.)

|

|

|

|

|

In Eritrea, every day is Big Hair Day.

|

|

|

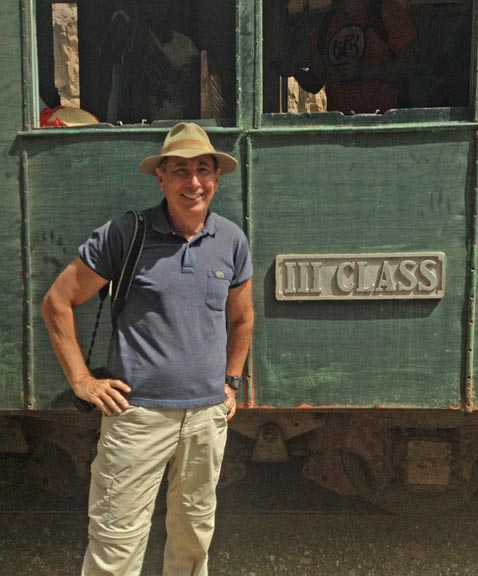

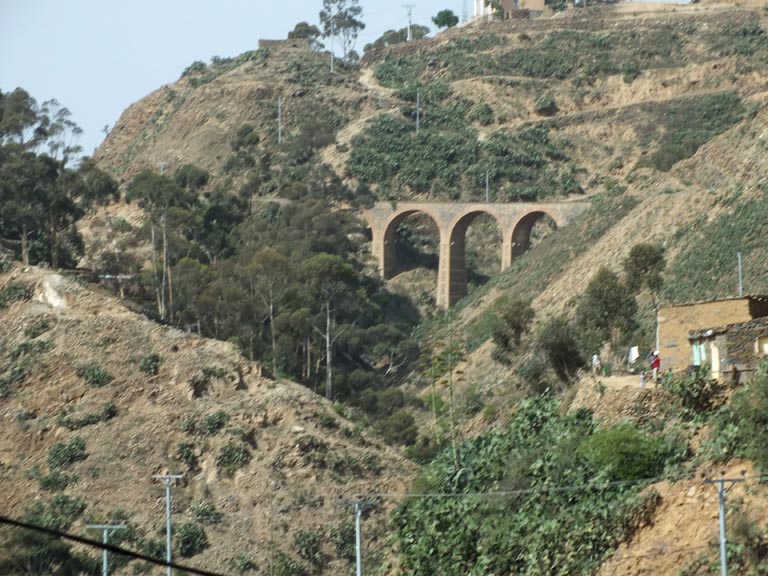

Sunday morning is our train ride. The completion of a narrow guage rail line from Massawa to Asmara was a major engineering feat by the Italians. A section of track remains in service. At the station, a 1938 coal-fired steam locomotive and a 1912 wooden passenger car are being readied. Our group has chartered this train at exorbitant expense, but the Italian and British ambassadors, their families, and other expats have invited themselves to join our excursion. (It turns out they have waited months for this opportunity. Since the previous tour a year ago, the train has only run on one other occasion.)

|

|

|

Not only is the equipment ancient, so is the crew, obviously called out of retirement. And although I like to think of myself as a 1st class guy . . .

|

|

|

With a plume of black smoke belching from the stack, we get underway. People gather along the track to watch and wave. Just beyond the city the terrain becomes rugged and the view impressive.

|

|

|

After about an hour we reach a station. The water tank is replenished and the engine reversed for the return journey. Sitting on an adjacent track is an old Soviet truck that has been adapted to run on the rails.

|

|

|

|

|

The return journey is equally entertaining.

|

|

|

In the afternoon we undertake a bit of indoor sport. Asmara’s bowling alley is unchanged from the 1950’s. By “unchanged,” I mean in continuous use without maintenance or replacement of equipment: the lanes are warped and unwaxed; the balls have huge chips and cracks; and the pins are battered and beaten. No automatic pinsetting machinery here: boys crouch down behind the pins to manually clear and reset the fallen pins and roll your ball back to you. They also keep score. Maybe not great sport, but great fun.

|

|

|

|

|

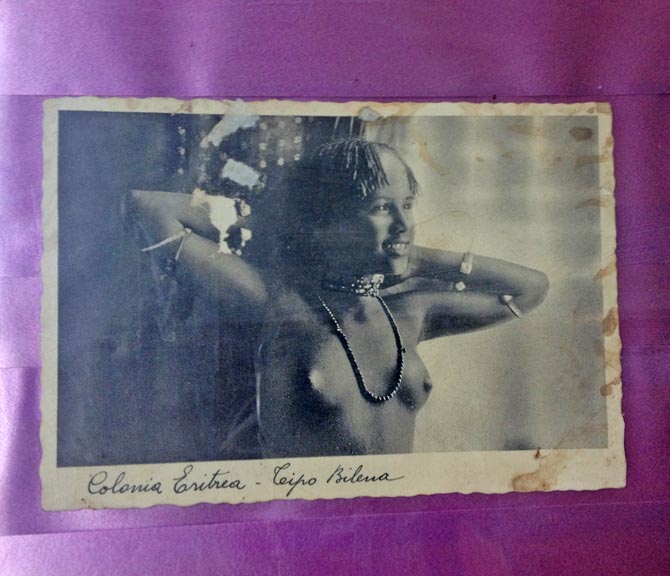

An added bonus: displayed on the back wall are vintage Italian postcards of bare-breasted maidens native to then-tribal parts of Eritrea.

|

|

|

We have obtained permission to visit Keren, the second largest city in Eritrea. We drive there on our last full day, Monday, the day of their weekly market. Along the way we pass a large mural depicting the approved story of oppression, struggle, redemption, and a shining future.

|

|

|

And more wrecked tanks.

|

|

|

|

|

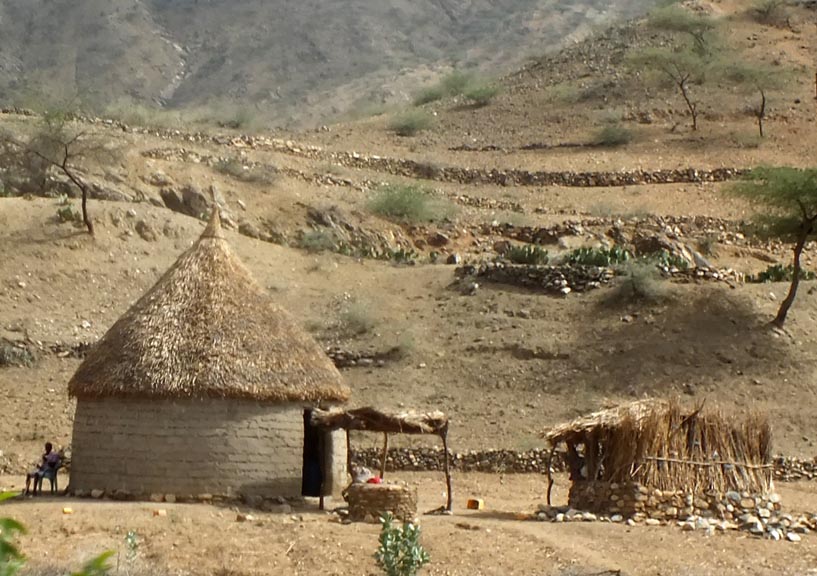

And traditional “African” huts.

|

|

|

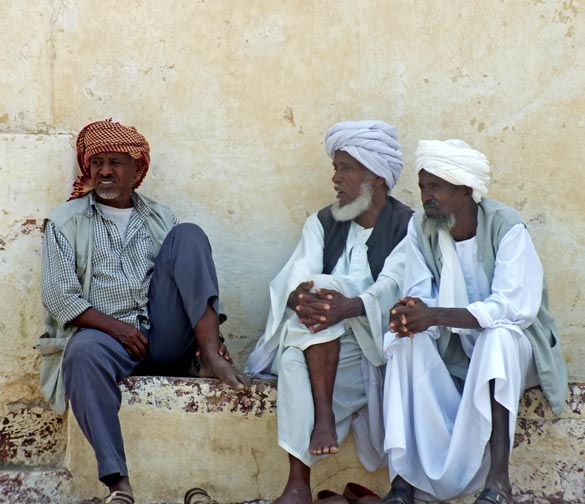

The market does not disappoint. It’s a visual feast: very colorful, though difficult to photograph. First, the people are very conservative Muslims who do not wish to be photographed. Second, the combination of bright sun, vivid colors and dark skin often obscures the faces of those whose images I manage to capture.

|

|

|

|

|

The women dress in bright colors. The men, not so much.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After the market we visit the Italian war cemetery. Like all proper military cemeteries, the graves are in perfect formation. The headstones of the Italian soldiers bear the name and rank; those of the Eritrean conscripts are simply marked “unknown soldier.

|

|

|

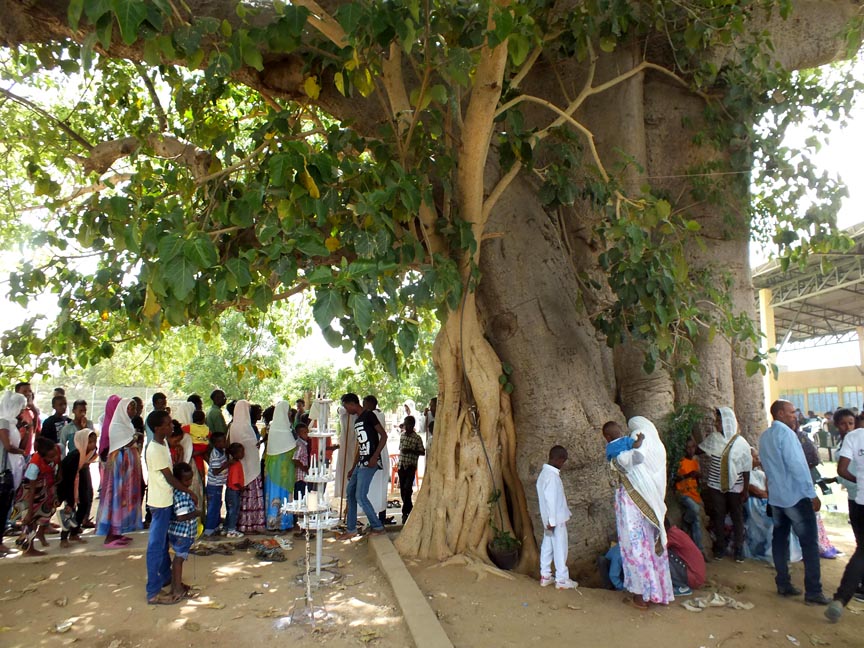

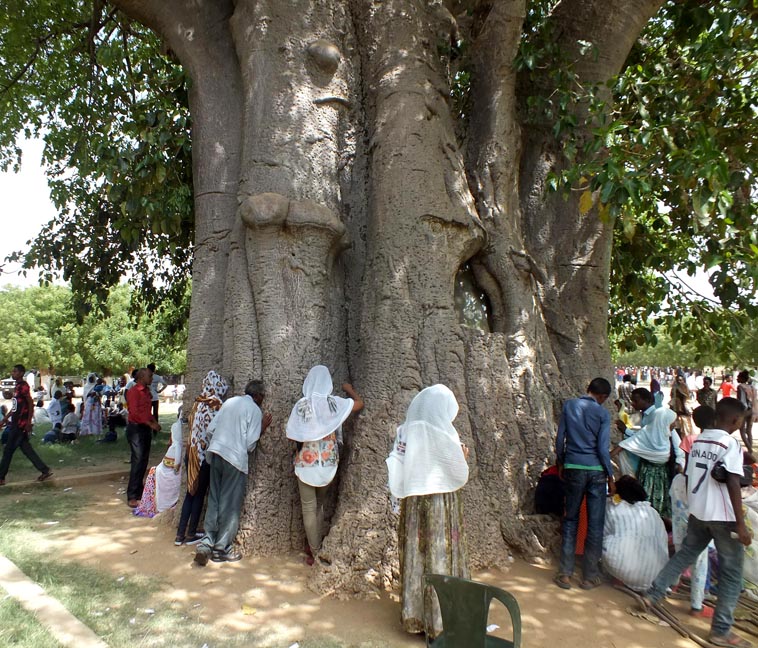

On the edge of the city is the shrine of Maryam Dearit, said to be the site where the pregnant mother of Jesus rested on her journey from Egypt to Axum (an event that your Bible probably somehow omitted). Also known as the Madonna of the Baobob, a statue of her resides in the hollow trunk of an ancient tree. Our visit coincides with the shrine's annual festival: on this date each year thousands of people from all over Eritrea come here to pray, dance, and sing.

|

|

|

The procession is a cultural, spritual, and family event.

|

|

|

|

|

|

That’s it. A week in Eritrea, Eritrea in a week. We return to Asmara for a final night before a morning flight back to Dubai.

Trip date: May, 2017