| The Devil's Island |

|

Mindful of the penalties for

unauthorized travel, I have vividly imagined a trip to Fideland and,

with the aid of Photoshop, created some very realistic pictures.

You

can't fly directly to Havana from the US, and, oddly enough, airfares from

other points of departure are roughly the same: no matter where you leave from,

Canada, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, or even Europe, it will still cost

you about $400. (Actually, there

is a direct flight from Miami; it costs $400 too.) I leave from Cancun, largely because it's cheap to get there

($134 + $90 tax).

Mexicana

will take a reservation over the phone, but it won't accept US credit cards for

tickets to Cuba. So at Cancun

airport I pay cash. Cubana has a flight leaving in an hour and it's cheaper,

but a sign at the ticket desk announces that $100 bills are not accepted. (They must not want to experience the

artistry of their comrades in North Korea and Hezbollah, who are expert

counterfeiters of Benjamin Franklins.) Thus, I am spared the ideological dilemma of putting money directly in

Fidel's pocket in order to save a few bucks.

Cancun

is a big, busy airport. There is but one, underused machine for wrapping

luggage in plastic. Normally, I

figure these machines are for worrywarts, but, having read about the honesty of

the baggage handlers in Havana, I decide to be a worrywart myself.

The

flight is only 50 minutes. From

the air, it doesn't look like Thomas Edison has had much of an impact in Cuba ?

there not many lights below.

The

first stage on entry is immigration, where the gal spends 5 minutes comparing

my visage to the very recent photo in my passport. Then, 10 minutes of interrogation, making sure that I don't

know anyone in Cuba. After that, a

careful inspection of my outbound air ticket. (Like anyone would want to stay!) Finally, I am passed.

The

next stop is the metal detectors. One expects these before boarding an airplane, not after getting

off! After that, a very thorough

patdown. Just like entering a

prison, which we are.

Then,

a queue to exchange our real money for prison scrip. Like the Soviet ruble, the Cuban peso is worthless. They used to use dollars for real

transactions, but now have something called a "convertible

peso." It's not real money,

but it's the only currency that will buy anything. All lodging, meals, and other purchases are priced in

convertible pesos. Each peso is

supposed to be worth a dollar, but they have now arbitrarily set the rate at

$1.08.

After

all of this, you would think that our luggage would be waiting for us. Welcome to socialist efficiency. Every few minutes a bag or two would be

placed on the belt. They are

working at the speed of inmates serving life terms, which they are. (Fidel's life.) At least 80% of the items have been

wrapped in plastic. After 20

minutes of waiting, mine arrives.

I'm

done, right? Hardly. As I head toward the "green"

lane at customs I am pulled aside. Apparently, it is my fortune to be selected for a quality assurance

survey. Clipboard in hand, the guy

starts asking me questions. But,

first, do I have a pen?

He

asks all the same questions I just answered, plus a bunch more. Then, he disappears with my

passport. Finally, he returns and

tells me I am free to go. By now,

they are opening everyone's luggage, and a long queue has developed. I seek out my erstwhile interrogator,

pointing to the long queue. My pen

still clutched in his hand, he tells the gal to let me through. Free (of sorts) at last!

The

taxi ride to town costs a month's salary (for them). We speed through unlit streets past crumbling buildings,

with few other vehicles on the road. I can see numerous figures disporting themselves in the dark.

My

hotel is a 1926 high rise which has been rehabbed and proudly sports 3

stars. It has elevators (one of

which is working) and AC. Apparently the rehab of the hotel did not include paint. I turn

on the TV ? satellite pirated from Mexico ? and there is CNN, MTV, and playing

on the movie channel, "Team America, World Police." What a great place to watch a satire

about meglomanical communist dictators.

In

the morning I venture outside. It looks like what I expected to see in

Beirut. This is Havana Centro, a

vast grid of complete urban decay. Across the street, in the window of a clothing store, are a few cast-off

bits of apparel. Next door is a

pharmacy; its shelves are nearly bare. The streets are a museum of cars from the 1940's and 1950's stilling

rolling along in various states of repair.

It's

a holiday of sorts: Martyrs Day. A

few days ago, July 26, was the big celebration, the anniversary of Castro's

1953 assault on the Moncada barracks, in Santiago, Cuba's second city at the

other end of the island. Fidel and

his brother Raul were captured, but, unfortunately, not executed. The attack is celebrated as the start

of the revolution.

I

walk the short distance into old Havana. Similar decay, possibly even worse, with some restored buildings

(European money). This is the

tourist district, and there are lots of them. Lots of stores too, but I quickly learn the rule: if a shop

is open and has anything you might want to buy, it's convertible pesos

only. (Although they are still

called "dollar shops"; convertible pesos are still widely referred to

as "dollars.") Ditto for

restaurants: if they have food, it's dollars only. You can buy almost nothing for pesos, giving new meaning to

the expression "your money is no good here."

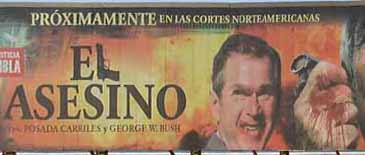

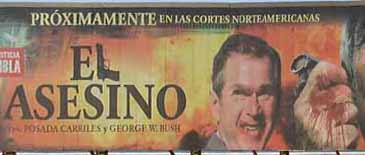

There may not be

anything to buy, but there is plenty of free propaganda. Instead of advertising products,

billboards are selling the party line. Quotes from Fidel are everywhere. Every city block has a Committee for

the Defense of the Revolution (its chief purpose is to spy on the residents),

and they compete with enthusiastic murals. As you might expect, every economic difficulty is blamed on

the US embargo. (Never mind that

they can buy unlimited food and medicine from the US, and Canada, Mexico, and

the rest of the world will sell them anything they want.) There are two themes: everything here

is wonderful and Bush is the devil.

|  |

Because

it is impossible to get by on one's government salary, everyone is hustling for

a buck. Corruption is

universal. Those unable to steal

from their workplace demand bribes for doing their jobs, i.e., checking in

luggage. On the street, I am

offered cigars every few feet. (A

sign at the airport warns that any box of cigars not bearing the hologram tax

stamp will be seized as "counterfeit." Hustlers approach me constantly, but even though I am not buying, they

really do want to talk. Everyone

has relatives in Miami. One guy's

father and brother left in 1980. Another guy's brother paddled a raft for four days to reach

freedom. They all hate the

government and want to get out themselves. They know exactly where Fidel places on Forbes list of the world's wealthiest men.

Dinner

is at the Hanoi restaurant. The

menu listings have Vietnam names, but the ingredients and preparation are

purely Cuban. I don't see any

oriental faces and I don't think any boat people washed up here. As in all restaurants, there is live

music. After playing a ballad to

Che, the musicians cadge the diners for tips. Very revolutionary.

The

next day I take a look at Vedado, the "modern" part of town. "Modern" is a relative term ?

with buildings dating mostly from the 1950's, it is somewhat less ramshackle

than the rest of the city. In

addition to hotels, offices, etc, it contains both the monument to the

explosion of the Battleship Maine and the Plaza de Revolucion. (Despite the exhortation, in Cuba they do not "Remember the

Maine.") The US Interests

Office, a quasi-embassy, is surround by propaganda boards and Cuban police to

keep people from approaching. Next

to it is the Plaza de Dignidad built for rallies to demand the return of Elian

Gonzalez. A forest of flags has

been erected to prevent Cubans from seeing an electronic news display put up the Americans.

| Monday is a slow day. The principal

activity is the Museum of the Revolution, housed in the former Presidential

Palace. It's overcomprehensive and

unairconditioned, but unmissable. Here, the visitor learns important facts such as before the revolution

dire economic circumstances compelled women into prostitution. Unlike today.

|  |

Behind

the museum is a giant glass case housing the Granma, the

cabin cruiser that brought Fidel and his band of merry men from Mexico back to

Cuba to relaunch the revolution. Surrounding it are tanks and planes

that defended against the Bay of Pigs invasion and the wreckage of a U-2 spy

plan they shot down.

On

Tuesday we depart Havana. The

major tourist cities are connected by a system of comfortable long-distance

buses. Dollars only, of

course. Inter-city transport is a

major problem for Cubans. Prices

are cheap, but you have to reserve a bus ticket at least three months in

advance. The government has

purchased a large fleet of new Chinese-made buses, but you rarely see them

running. Instead, they are parked

at the station. At every road

leading out of a town or city great throngs of people are standing around in hopes

of getting a ride. Some wave money

to flag down passing cars. Others

climb aboard the open backs of trucks. A government agent is present to place people on all types transport and

to collect fares. City buses

frequently are converted trucks. Outside of Havana taxi are usually bicycle rickshawss or horse carts.

|  |

|  |

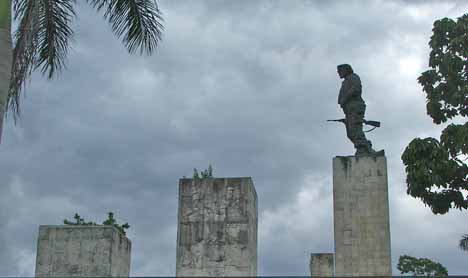

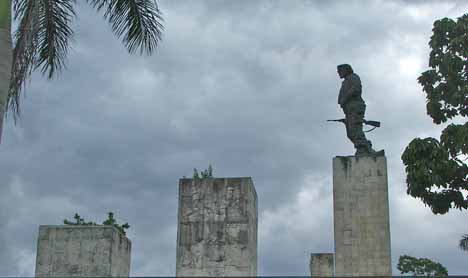

Our

first stop is Santa Clara, about four hours from Havana. On December 29, 1958, Che derailed an

armored train here. The soldiers

aboard surrendered almost immediately. Two days later Batista fled Cuba and Fidel ascended the throne. The railroad cars have been left in

place and turned into a museum of the Battle of Santa Clara. The town later "adopted" Che

and built a huge memorial with giant statue and a museum. The museum contents are mostly

photographs and various items touched by the hand of Bonaparte ? my favorite is

a "Zippy Zither" along with the score to "Home on the Range." Now there's an image: Che drumming his

zither and longing for where the buffalo roam. Across the hallway is a chapel-like area with a green copse

suggesting the Bolivian jungle where his carcass rotted away. In 1997, thirty years after his

death Che's bones were located, identified by DNA, and moved here. Unlike other museums, this one is air-conditioned, which encourages the visitor to

linger.

This

is our first night in a casa particular. Outside the capital,

hotels are few. People are allowed

to rent out spare bedrooms to tourists and offer them meals. It's heavily taxed and regulated, but

gives many people access to vital dollars, and the competition is fierce. Each arriving bus is met by a crowd of

women with cards describing the attributes of their casas. It's cheap, and a great opportunity to meet the people and see how they

live.

Tonight

the air is electric ? Fidel has undergone emergency surgery. For the first time in 47 years, he has

temporarily ceded power to his brother, Raul. When the 6:30 news comes on, everyone is glued to the screen. From the buildup, tributes, and lack of

any actual hard information, I figure El Barbero is a goner. Instead of reporting on his condition and a prognosis, the entire

newscast consists of fluff. Our

landlady is a true believer ? when the party hack announces that all will be

fine, she applauds along with the toadies on the screen. Meanwhile, in Miami, they are dancing

in the streets.

There's

really nothing else to see in Santa Clara, so the next day we move on to

Trinidad, a gem of a colonial city with postcard scenes around every

corner. The city is also home to

the museum commemorating the war against the banditos. Castro and his men were revolutionaries who fought FOR the people. Those who resisted his rule were

bandits and pirates. In this part of island the fighting

went on for years.

The

next day is a rail journey of sorts. A line built to haul sugar from the fields now takes tourists in open

carriages 15 miles out into the lush countryside. After a few hours, it makes the return journey. It are supposed to be pulled by a 1919

steam locomotive, but they must not have gotten it working that day because

ours is a diesel. Due to delays,

the trip takes the better part of a day, but a very scenic and pleasant one.

The

third day in Trinidad is a horseback ride. We depart from the edge of town and enter a national

park. After about an hour we

dismount for lunch and to hike to a waterfall, where some go swimming. Then, the reverse route back.

On

to Camaguey, about a six hour bus ride to the east. The Trinidad bus station has an air-conditioned waiting

room, but to get in it you have to show your passport (that you have one) ?cool

air is for foreigners only.

Camaguey

is supposed to be a charming colonial town, but it is a lot of nothing. We decline dinner at the casa only to find the restaurants are closed on

Saturday night. I think they show

respect to the rights of their workers by being open Monday-Friday, 9-5. We finally find an overly noisy bar

that serves food.

There's

not much to do but walk the streets and look in the shop windows. After almost 50 years of communism even toothpaste is rationed. The peso stores all sell the same few

items, although one distinguishes itself with an ample supply of little plastic

buddhas. The paucity of goods for

sale is supplement by ample propanda displays. A repair shop advertises that it

repairs both "soviet and capitalist" TVs. (Our casas

often are equipped with "Minsk" brand refrigerators and other Russian

appliances.) The typical building

consists of an empty storefront with someone sitting at a desk to

"greet" visitors.

One

day here is plenty. On Sunday, we

move on. The Camaguey bus station does not offer airconditioning , but it does

have a large photo display commemorating Fidel's visit there. En route to Santiago, another six hours

to the east, the driver periodically stops to conduct some private business,

which seems to include the transport of goods and selling of empty seats. The scenery is mostly fields of sugar

cane.

All

of Cuba is lush and fertile, yet the country can't feed itself. It suffers from typical communist

agricultural efficiency ? there is little point in working hard to grow stuff

when you don't own the land and can't sell your crop. I don't see any intensive cultivation; even the sugar fields

look sparse. Despite plenty of

pasture, cattle are a rare sight. Beef is almost unobtainable, and dairy products are strictly rationed.

Although

eclipsed by Havana, Santiago is where much of Cuban history happened: where

Columbus landed; where the rum industry began; where independence was forged;

and where Castro came from (nearby), fought, and triumphed. It is much poorer then the capital and

much blacker, the descendants of slaves having created an Afro-Caribbean

culture. It has far fewer

tourists, far more decay, but is livelier. | The

Bacardi rum empire was headquartered here. A tour of the Museum of Rum, which I refer to as the Museum

of Me (rum in Spanish is "ron"), includes a free shot of the

product. The Bacardi assets were

seized by Fidel and now produce the Havana Club brand, which is solely for

export. The museum manager laments

that he cannot afford it on his salary of $15/month. It's also sold in the dollar shops and, largely untaxed,

costs only a few dollars a bottle. Cigarettes are cheap too ? about 35?/pack. I don't smoke, but at these prices I ought to start. |

|

The

velvet ropes part as we enter the very elegant 1900 Restaurant for lunch. The menu prices are reasonable; too bad

there's almost no food (and no other customers). They have to send someone out into

the street to fetch us a can of soda. Like all restaurants, it's owned by the

state. They is plenty of staff,

but very little service. Restaurants add a 10% service charge to the bill, but either the staff

gets none of it (mostly likely) or they haven't grasped the concept. Even if you pay baksheesh the level of

service from state enterprises (which is all them) is maddingly poor. It's exactly like the old Soviet Union,

where they would joke "we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us." I mentally bestow "Hero of Socialist

Labor" awards on the worst.

Emilio

Bacardi's personal collection forms the basis of a very eclectic museum,

featuring art, archeology, historical items, and the only Egyptian mummy in

Cuba. My two favorite objects are

the shrunken head and the handkerchief embroidered with the name "Fidel

Castro Ruz" (that's his full name).

Tuesday,

we hire a neighbor to drive us around in his 1949 Ford. The first stop is San Juan Hill, up

which Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders charged. The site is covered with memorials to US soldiers. These days

though, the sympathies are with the overwhelmed Spanish defenders. Unlike the

Maine Memorial in Havana, the monuments have not been damaged.

Santiago

has a magnificent natural harbor (as does Havana), the entrance of which has

been guarded for over 400 years by El Morro,. The fortification has been impressively restored and contains a number

of historical exhibits. One

explains the difference between buccaneers, filibusters, pirates, and

corsairs. Another is devoted to

the 1898 naval Battle of Santiago, in which the US fleet sunk its Spanish

counterpart in short order. A

modern plaque is dedicated to the Spanish victims of this

"holocaust."

One

can drive to the town of Guantanamo and peer at the US naval base through

binoculars, but we don't because it's far from the city and you can't see

anything anyway.

My

druthers are to take the train back to Havana, but the only one that offers

minimal comfort isn't running today. There is an overnight express bus which makes the trip in 12 hours, so

that's what we take. At the

station, I ask about a drink and learn that the nearest refreshment is 4 (long)

blocks away. A few minutes prior

to departure a security guard shows up with a cold soda, for which I give him a

dollar. They're learning.

Back

in Havana, rather than waiting three hours for a connecting bus we hire a

private taxi (i.e, a guy with

a car) to drive us to Vinales in his 1960 English Ford. He has won the visa lottery and will

shortly be leaving with his family for the US. Twenty thousand immigrant visas a year are given to Cubans,

mostly for family reunification but some allocated by lottery. His English is good ("that is the

language of America"), honed by watching satellite TV from Miami. (His neighbor has an illegal dish, and

the signal is piped throughout the building.) He has to pay about $900 in exit fees and he is not allowed

to sell his car, but he is a happy man.

Everyone

knows that Fidel is a short-timer, but, after 47 years, people have given up

hope for real change. Both the hardcore, who have faith in Raul, and the

dispirited majority suffer from a lack of vision ? they can't imagine a

different Cuba. Almost everyone

hates communism, but they don't want the Miamians to take over either. I thay had half a chance, a large portion of them would just leave.

Vinales

is depicted on all the travel brochures for Cuba. It is in a verdant valley surrounded by limestone formations

amidst tobacco fields. The

standard package tour of Cuba includes a drive out from Havana and a night at one

of the big hotels for foreigners outside of town (Cubans are not allowed in

hotels). A steady stream of tour

buses rumbles down the mail street of the small town. We stay in a casa.

The attraction is the

scenery. We take a half day

walking tour through the surrounding countryside. Our guide is both surprised and disappointed that I don't

have an opinion on the White Sox. (Baseball is the Cuban national sport.)

The

limestone formations in the area contain a number of cave systems. On our walk,

we pass through one. Very

dark. Others are rigged for

visitors. In the afternoon we

visit one that features a boat ride on a subterranean river. We get stuck with a giant tour

group. It's mass tourism at its

worst, but it gives us an opportunity to be grateful that this is our only

encounter with what most visitors to the island endure their entire

trip.

The

next day is another horseback ride through a different part of the valley. The finest cigar tobacco is grown in

the Pinar Del Rio region, of which Vinales is part. We visit a tobacco grower whose produces for Cohiba and he

offers a sample ? a $10 cigar without the band. The farmers have small plots (less than 1 acre) and live

simply, without electricity. They use bullocks for plowing. The tobacco growing season, which lasts

3 months, is over and the fields are now planted in corn.

In

the afternoon, we bus it back to Havana where we have an extra day. The interior of the Capitolio proves worth the $3 admission price. The former meeting place of the Cuban

congress, those days it hosts ceremonial events and is home to a rare internet

cafe. What may be the most

beautiful and ornate building in Cuba is underplayed by the government,

possibly because it belies the official position that nothing significant

occurred during the period of the "pseudo-Republic" prior to the

Revolution. I also discover the

fixed-up portion of Old Havana, which eluded me last time.

El Dinosauro is still hanging on. The party newspaper (the

only kind they have) reports that speedy-recovery wishes have arrived from

North Korea, Venezuela, Bolivia, China, and the other usual suspects. A foreign expert is quoted

declaring Fidel to be the greatest figure of the 20th century. Tomorrow he will be 80. "At his request," celebrations

have been "postponed." Still, over at the Plaza de Dignidad are

musical acts interspersed with tributes and slogans. Above the stage is the banner proclaiming "Fidel

Siempre" ("Fidel forever"). We watch it live on TV.

Sunday,

August 13th. This is it, the 80th

anniversary of the emergence of El Vampiro. No one seems to be

paying it any mind. The only

discernable difference is that the normal 57 varieties of police stationed

every few feet have been augmented by grey beret wearing special police, who

are kicking ass and taking names. I wonder how many years you get for smirking?

It's

also leaving day. Our youthful cab

driver to the airport is another #1 USA fan. Ten years ago his father escaped by a boat and now lives in

Jersey City. In a year or two, he

hopes to join him there. In the meantime, he, too, is perfecting his English. I wish

him well and tell him that, with luck, he won't have to wait that long.

Trip date: August 2006.