Oh the things I do to bring you these great pictures! (Note self-sacrificial tone.) On Thursday I get picked up at 4 AM for the Geyser Tour. For two hours we bump over unpaved roads to reach the geyser field before sunrise. Frankly, I wish our driver wasn't in such a hurry -- the temperature when we arrive is about 0° F. I did not bring my arctic gear and am wearing all my clothes -- two T-shirts, two long sleeve shirts, a sweater and a jacket, plus two pairs of socks -- and I am

still freezing. We may be in the tropics, but we are at 13,000 ft.

I find a steam vent to stand in while the driver uses a boiling pool to heat our breakfast. Sunrise brings rapid relief as well as better photos.

Next on the agenda is bathing in the hot pools, which ain't for me. I am happy to ogle a gaggle of skinny Nordic chicks in bikinis until the scene is polluted by the arrival of euro-chubbies.

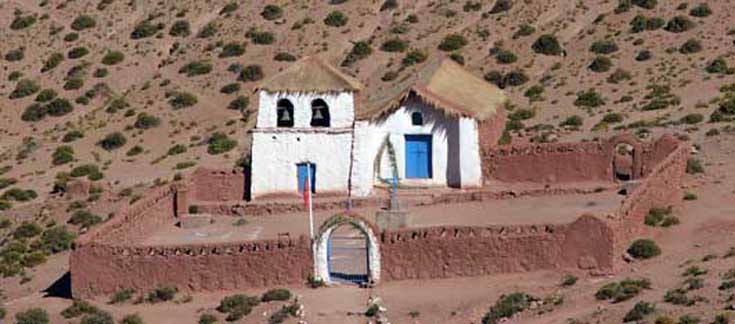

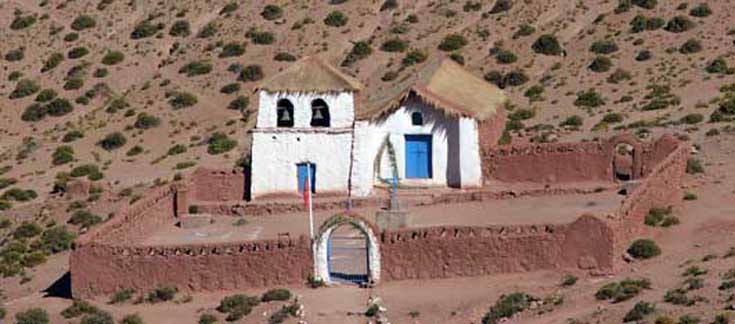

On the way back we stop at a tiny village with a pretty little church. They are grilling and selling what could be a hit at next year's Minnesota State Fair: llama-on-a-stick. Verdict: better than other camelids I've tried.

There's also some good wildlife sightings in the altiplano -- more vicunas and a nandu (rhea), a first for me.

Onwards to Argentina! There are six buses a week to Salta run by two companies, but they leave at identical times (go figure) so there are effectively only three. Salta is in the extreme northwest of that country; all I know about it is that I saw a very pretty travel poster a few years back.

There is nothing between San Pedro and the border, so the Chileans sensibly locate their border formalities in town. We load up the bus, drive a couple hundred yards, then pile out to get our passports stamped. It takes about 3 seconds each to process the gringos but forever for the locals, so the whole deal takes about an hour.

The Argentinean border post is near the actual frontier on a desolate, windswept mountain pass. Getting through takes another hour with the same foreigner/local dichotomy. At least they don't make us unload our bags for customs.

The scenery enroute is very good, much like southern Utah. My seatmate is a cute Brazilian girl who convinces me that one can travel in Brazil knowing only rudimentary Spanish. When darkness falls I pull out my DVD player and share three episodes of

The Sopranos, which she has never seen and thoroughly enjoys.

With the two border delays plus a hour time change, after nine hours of travel we arrive in Salta at 10:30 PM, twelve hours (by the clock) after departure. The bus station ATM is out of order, and there is no exchange kiosk. However, the taxi driver is quite happy to take me to my hostel for $2 US.

Saturday morning I set out to explore the town. It's a bustling place with over a million inhabitants, a sharp contrast to San Pedro where dogs sleep undisturbed in the middle of the street. There are some nice looking churches, and the interior of the cathedral is especially impressive. I visit the 18th century home of a wealthy family that produced two presidents. Now a museum, it is full of dark Spanish furniture and dark family portraits. In the main plaza, buskers dressed as Indians with feathers in their hair are playing "Don't Cry for me Argentina" on Peruvian flutes.

Tourism is a big industry here. Lots of outfits are pushing full and multi-day trips to see the sort of scenery I just came from. A major attraction is "The Train to the Clouds," a former mining route reinvented as a tourist train and just reopened after a three-year shutdown. I decide against it for three reasons: 1) it sounds like a tourist trap; 2) it costs $140 for foreigners; and 3) it leaves at 7 AM and gets back around midnight, too much of an ordeal for me.

Although expensive for South America, Argentina is still relatively cheap for gringos. Since the peso collapsed in 2002 from 1:1 to the US dollar, the exchange rate has stabilized at 3:1; in the meanwhile peso-dominated prices have increased about 50%. The most immediately noticeable problem is a coin shortage: no one has any. Stores post signs saying "no coins." The smallest bill is the two-peso note, so minor items are offered in multiples for two pesos. It must be rough on beggars, street performers, and those who depend on tips who are unlikely to receive folding money. The ATMs dispense 100 peso notes for which it is extremely difficult to get change.

In the central market I find pirate videos, which are conspicuously absent in Chile. They are cheap enough, 4 for 10 pesos, but both quality and selection suck. It's pretty much all generic action, horror, and stupid comedy flicks; it appears that the entire catalog was chosen by a 14 year-old boy. And they are not even DVDs, they are video CDs burned onto blank discs with handwritten titles. (In China, for that price you get perfect copies with full cover and sleeve art right down to a counterfeit security hologram.) I manage to find a few current releases, and the clarity is good enough for my 7" screen.

In the afternoon I take the cable car to the top of a hill overlooking the city. The difference between it and the one in Santiago is manifest; the nameplate of the Swiss manufacturer is prominently displayed at the base. At the top there is not much to do except take a picture and come back down.

There's still time for a trip to what is described as the charming village of San Lorenzo. The bus only costs a peso. What I find is an upscale suburb with big houses and a few restaurants and hotels. Just above the town is a heavily visited gorge, the

Quebrada de San Lorenzo. (I had to look up the word in my dictionary, where I was surprised to learn that there is only one page of "q" words.) I am under whelmed. It is just a mountain stream and is particularly unimpressive in comparison to the spectacular Andean scenery nearby.

| On Sunday morning I complete my Salta card and visit the Archeological Museum of the High Mountain. It is really just one exhibit for which they get a pricey 15 pesos (from foreigners, 5 for locals, one of the few instances of dual pricing). In 1999, an expedition found an Inca sacrificial platform peak with three child mummies and about a hundred artifacts atop a 22,000 ft. Due to the extreme cold and low humidity and pressure, the state of preservation is perfect right down to the brilliantly colored feather decorations. (There was no deliberate mummification process; they were sacrificed and freeze-dried in situ.) There is a 7 year-old boy, a 6 year-old girl, and a 15 year-old girl, whom I dub "Miss Argentina." The exhibit consists of contextual preliminary displays, some of the artifacts, and one of the mummies. What appears to be a display case is actually a corner of a preservation freezer in an adjacent conservation laboratory. The display freezer, which replicates the 0°F temperature and other conditions of the mountaintop, has one glass corner which juts into the museum. The other two mummies are in other freezers, and they are rotated every few months. The boy is on duty now. Photos are prohibited, but for my five dollars I feel entitled to sneak one |

|

I originally planned to backtrack through Chile but I have altered my plans and now will continue south through Argentina. Mendoza, a short 19 hour bus ride away, lies across the Andes from Santiago. The lie-flat sleeper buses are booked up a week in advance but seats on the

semi-cama's of the type I have been taking so far are readily available. Mid-afternoon on Sunday must be an unpopular departure time because my bus is almost empty. As we head south on the highway the sun is on the left, predictably backwards. The ride is comfortable enough, a hot meal is served, and an English chick is delighted to be introduced to Season 5 of

The Sopranos.

Mendoza is a pleasant city of tree lined streets and handsome plazas, but there is really nothing to see. The oldest buildings were knocked down in an earthquake 150 years ago, and there has been little built since that is noteworthy. This is the adventure tourism capital of Argentina, but I don't want to go skiing, it's too cold for rafting, I'm not one for trekking, and mountain biking is not my cup of tea. Oeneophiles flock to here, but vineyards and wineries hold little attraction for me.

The first day, Monday, I spend wandering about enjoying the glorious sunny, shirtsleeves weather. The Central Market has been gentrified (no pirate video vendors here!) but it's still a place to find good, cheap restaurants. When in Argentina, I make like the Romans and switch to beef. When not scarfing down grilled meat, they are popping

empañadas, meat filled pastries that are sold by the dozen. I have three for lunch and am ready to skip supper. I note that a well-known Scottish restaurant chain has established a branch here (haven't seen a McD's since Santiago), but I am not even slightly tempted. After lunch, everything shuts down tight. Despite the lack of climatic justification, siesta is rigorously observed.

Tuesday morning I loll about the hostel till noon, and spend the afternoon hiking across town and through a giant park to the top of a hill upon which stands a very impressive monument to San Martin, the George Washington of Argentina (and nominal commander of O'Higgins). With all the glorification of "liberation," I don't suppose that anyone ever asks the impolitic post-colonial question of just exactly how this or any other South American country benefited by ousting the Spanish? The politics here is all shades of Peronism, which seeks national prosperity through redistribution. Yeah, that's worked out well.

I have a day to kill before my Friday flight from Santiago. I opt to waste it here because, even though the temperature has dropped 20° from yesterday, the low here is equal to the high in Santiago. My only achievement is catching up on this trip report.

The bus from Mendoza to Santiago is a big semi-cama. Ten minutes prior to the scheduled departure, I am the only passenger. In the office a guy is buying his ticket. (In an amazing coincidence, he has the identical piece of luggage as I do, and because he is a local I doubt he got it at Wal-Mart.) At the departure time, six more people show up. It takes twenty minutes to finish their paperwork for the trans-border manifest.

When we pull out of the station it's raining, which soon turns to snow. We pass miles and miles of snow-covered vineyards and then climb into the mountains. (When the snow gets too deep, they close the pass.) After the first set of ridges, the precipitation ends and it becomes bone dry. That is why the Amazon is a jungle and northern Chile is a desert.

You can tell we haven't crossed the continental divide because the river we follow is flowing east. Also along the route are the abandoned tracks of a narrow gauge railway. This is where the Pan American Highway crosses from the west coast of South America to the east, from Santiago to Buenos Aires and thence down to Tierra Del Fuego.

The border formalities take over two hours, including a luggage drill. Once again, the actual processing is very quick but this time there are several busses ahead of us.

Then comes the big scenery, the high Andes at its best. It's amazing when you think that they used to cross them on foot.

It's nice to arrive at a familiar place and not have to try to not look bewildered as the usual mob of taxi, hotel, and other touts converge on you as you alight from the bus.

I have an 8 AM flight to Easter Island. Because it is so early and it is raining, I break habit and shell out for a taxi to the airport. Foolishly having failed to check in on line the day before, I find myself stuck in a middle seat on a completely full plane.

Six hours in the back of a plane is worse than nineteen on a bus. By the time we land I think I am crippled. We cross 2300 miles of empty Pacific Ocean to the most remote inhabited place on Earth, halfway between South America and Tahiti. When we reach the island, there's no landing pattern-- the approach is straight in at six hundred feet over the ocean.

The airport is tiny, but it has the longest runway in Chile -- it's an emergency-landing site for the space shuttle. Working the control tower must be one of the cushiest jobs on aviation since the maximum traffic load is one flight per day. I am a little disappointed that they don't have big heads lined up beside the runway.

In the terminal the small hoteliers and guesthouse operators are competing to snag arrivals who have not already arranged accommodations, which seems to consist only of me. (The airfare pretty much keeps this place off the backpacker route.) They are offering the most perishable of products; it's not like they will get a drive-up or walk-in guest later. One reason I planned on three days here is because I thought it would cost me two arms and two legs for a place to stay. The bidding war starts in dollars and switches to pesos. I end up with a room with bath plus breakfast for less then $20/day.

Almost all the ~3600 inhabitants of Easter Island (

Isla Pascua in Spanish,

Rapa Nui in Polynesian) live in Hanga Roa, the only town. The island was once densely populated but famine, disease and slave raids reduced the number of natives to 111 by 1878. To better Christianize them everyone was forced to live in town, an edict not lifted until 1965.

I spend my first afternoon walking around and near the town, which, an hour after the plane has left, has returned to its normal somnolescent state. There is a bank, a supermarket, a pharmacy, a church, and lots of tourist shops and services. The gas station needlessly posts its prices even though if you don't like them and you want fuel the nearest competition is 1400 miles away. There is also a building designated "Rapa Nui Parliament" with a giant billboard quoting some UN anti-colonial resolution. Sure, let's give them their wish: have the Chilean navy pull out and we'll see how long before pirates, mercenaries, and modern-day slavers move in and take over.

Near the harbor are a couple of smaller big heads, and there is a larger group just outside of town. The big head era lasted from about 1000-1400, later supplanted by the "birdman" cult. In a period of around 50 years around 1800 all the big heads were pulled down in internecine wars. There are just over 800 of them, of which about 400 are still in the quarry, another 100 or so abandoned in transport and the rest on site. Of the latter only about three dozen have been re-erected, the first in 1955 (by Thor Hyerdahl) and the most recent about ten years ago.

|  |

Nowadays you are not allowed to climb on the platforms or even touch the statues. Valuable employment has been created in the form of hiring people to stand around with megaphones to yell at tourists who get too close.

There is a small but informative museum. The best artifacts are in museums in Chile, Europe, and America, but they do have one of the two big head eyes ever discovered, the others having mysteriously disappeared.

In the evening the town wakes up, and rather noisily, as every kid seems to have an unmuffled dirt bike. And just about every private vehicle is a self-styled taxi as the owners drive around trying to cajole tourists into giving them ten or twenty dollars for a ride across the few blocks that comprise the town.

I consider renting a vehicle for my second day. There are all sorts of choices: bicycles, motor scooters, dirt bikes, quads, cars, and even horses, but none are cheap. I end up signing up for a $50 all-day tour that takes in most of the sights. Sure, I will learn and see more with a guide, but my principal reason is that I need someone to take pictures of me with the big heads.

The tour is the right size, just two: me and a guy from California plus the guide. We jump ahead of the other tour groups by skipping the first site and going straight to the quarry, where we are the first to arrive.

All the big heads were carved at the crater of one of the three volcanoes that formed the island. (The red hats that some of them wear come from another crater.) They range in size from about 6' to 60'; the biggest was never finished and probably never could have been moved. Big heads in various states of completion and transport cover both the inner and outer slopes of the crater. We spend over two hours walking around, the guide pointing out things I never would have noticed.

From the crater rim the vista towards the sea is of the biggest and most impressive platform on which sits a line of fifteen big heads. The site was restored by a Japanese crane company. (Back story: a documentary on Japanese TV lamented that without a crane the toppled statues would never again stand upright, and an exec watching volunteered one for the PR value.) The biggest one of the group is 30' tall and weighs 100 tons. Like all the big heads, except for one group of seven, they are on the coast and face inland.

Then we backtrack to see an unrestored site. Sixty years ago they all looked this way, the big heads fallen and broken amidst the scattered stones of the supporting platform.

Finally, we go to a sandy beach, one of only two and where tradition holds the Polynesian voyagers first landed their canoes. (The rest of the island's coast is very rugged and lacks a protective reef.) A set of restored big heads in very good condition (they were covered in sand that protected them from erosion) and replanted coconut palms makes for a very pretty picture.

|  |

That's it for the day. If we moved along faster we could get more in, but that would be against their interest because they can sell more tours by dividing the sights into different packages.

As you might expect, stuff is pretty expensive on the island. A supply ship comes every two months. If you want something, you either pay for air freight or wait. I would like to bring back a big head the size of my suitcase, but they are priced for buyers from the Getty Museum (and very poorly made). Unlike the supply of hotel rooms, souvenirs are not perishable, and the vendors know that if they do not make a sale today, tomorrow or the next day will bring a new planeload of potential purchasers. (And in another two months, the ship will bring another load of $30 T-shirts from China.) I settle on a 6" version.

Sunday morning at breakfast we are treated to Jesus music. The Polynesian-style hymn singing over at the church is supposed to be interesting, but I'm too lazy to go check it out. Considering that this is a 100% tourist economy, I am surprised that just about everything is closed today.

I undertake the 2+ hour trek to the rim of the third volcano, the one nearest town. The views both into the crater and over the town are excellent. At the top is a ceremonial village and petroglyphs from the birdman cult. It's a tiring walk up, but downhill is considerably easier.

I have missed one group of big heads, a line of seven with eyes on a hillside facing the sea, but I don't sweat it. I already have more big head pictures than anyone will want to see. But come sunset I trot over to the nearest to add to the collection.

My GPS says its only 4300 miles to Jacksonville, but in the absence of a direct flight it takes from Monday morning to Tuesday afternoon to get back. (Bill Gates doesn't have this problem.) I take some consolation in that the plane back to Santiago has come from Tahiti and is a new model with better seats and on-demand video. The American Airlines plane to DFW is the usual crate. One more hop and I am home.