|

To even figure out where and what is Somaliland, it helps to start with a bit of history.

The European powers divided the Somali coast and interior into French Somaliland, British Somaliland, and Italian Somaliland (including Puntland). The French colony is now Djibouti. In 1960 the former Italian and British colonies merged into a united Somalia with a capital at Mogadishu; that did not work out well. In 1991, following years of repression, Somalia disintegrated into civil war and the former British Somaliland declared independence. Although that year witnessed the rebirth of nations in post-Soviet Europe and democracy movements in Asia, the cardinal rule of post-colonial Africa has been no secession and no border adjustments (Eritrea and South Sudan being the exceptions). Thus, almost all maps show Somalia as a single country governed from Mogadishu.

|

|

Today, although Somaliland has its own government, military, currency, and conducts taxation, customs, visa issuance and border without regard to the regime in Mogadishu, no other nation in the world has recognized this independence. The country, although poor, is relatively corruption-free, has honest elections, and is orderly and safe for travel. This is in contrast to the chaos of the failed state of Somalia, where Islamist militias run rampant, and Puntland, another autonomous region where P is for pirate.

I, along with my friend Agustin de Mexico, have joined a tour timed to coincide with the annual independence day celebrations. Last year, the 25th anniversary, was a big blowout. Unfortunately this year, as we find out, there will be no military parades or other public festivities: they have been canceled in favor of relief programs for the drought that has devastated the entire region.

|

|

|

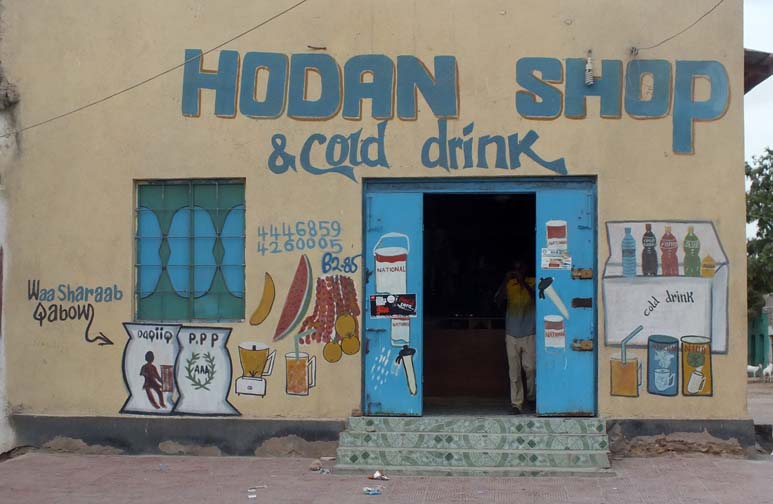

The flight from Dubai lands in Hargeisa, the capital. Definitely not a garden spot: it was pretty-well bombed flat by the Somali government in the war preceding independence. These days, investment by returning Somalis has sparked a building boom, and new construction has sprouted everywhere. There is a modern telecom system, reliable electricity, and even a Coca-Cola bottling plant.

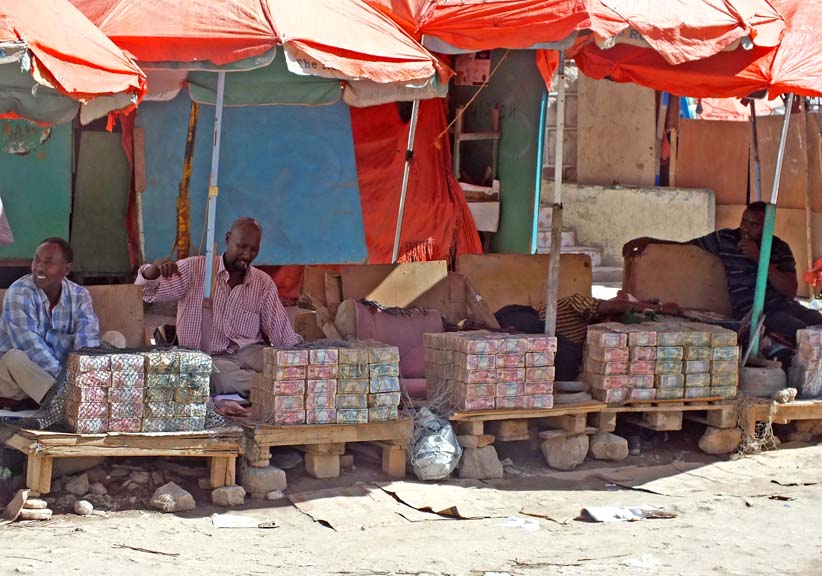

Our hotel is smack in the middle of the central market. Directly in front are money-changers with huge stacks of Somaliland shillings (8500 = $1). Business is slow because all transactions larger than a dollar take place in US greenbacks with the local currency used only used as small change.

|

|

|

Somalis tend to be tall and slender. The women dress colorfully, but, as very conservative Muslims, are covered up and camera shy. Even the men are photo adverse. English is widely spoken, and it seems that everyone is eager to tell you about his relatives in America and England.

|

|

|

|

|

On our first day there are no activities scheduled. On the next we venture out to twin peaks known as the “two breasts” (the Grand Tetons of Hargeisa?). Not hugely interesting in itself, but the route there passes squatter camps (we are unable to get a satisfactory answer on where the squatters are from) and a rocky burial ground where several funerals are in progress.

|

|

|

On the way back we stop at the British War Cemetery. The headstones bear exotic names of empire such as the Kings African Rifles, the Somaliland Camel Corps, and the Punjabi Infantry Regiment. Christians, Muslims, a Hindu and even a Jew have found there final resting place here together with one “Soldat Bombomgo” of the Force Publique du Congo Belge.

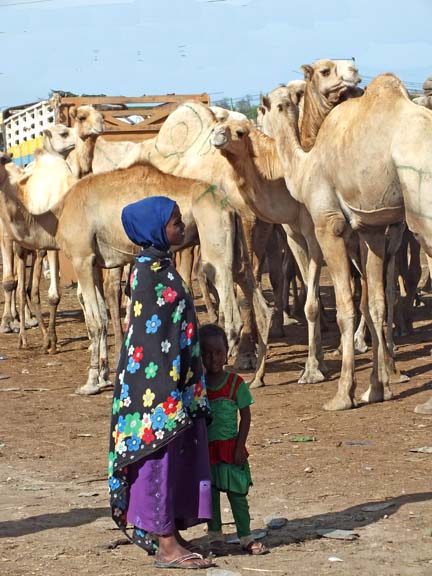

The next morning we visit the camel market. These beasts ain't cheap: an adult costs upwards of $1000.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Afterwards we repair to an early lunch. Camel is considered a delicacy, and the restaurants that serve it are usually sold out by noon. To my surprise the meat is tasty and tender. The hump is pure fat, which I eschew but the locals love.

|

|

|

Generally speaking, the food is edible but unexciting. Meat is mainly goat served with pasta and rice with the occasional lamb or chicken dish. A welcome alternative are restaurants run by Syrians who have fled their civil that serve Arabic food.

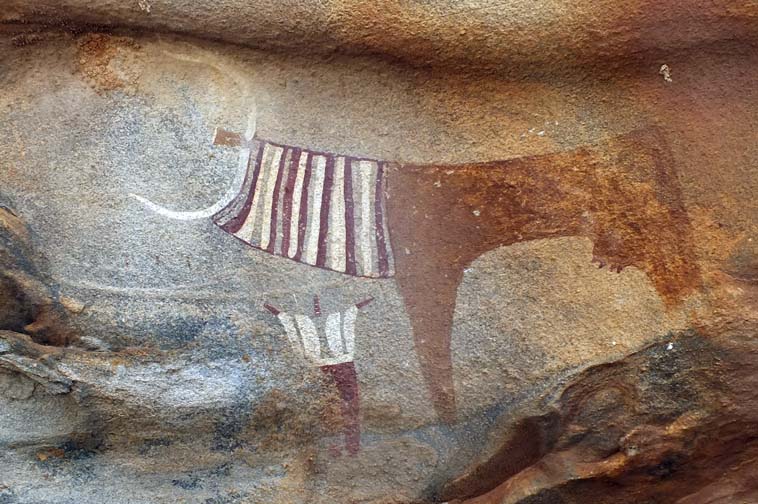

The next day we drive into the desert to see the cave paintings near Las Gheel. There are multiple "caves" (really rock shelters) that were painted over a long period -- estimates of their age range from 3,000 to 8,000 years old. Our visit is a bit hurried because of the threat of rain: the dry river beds we crossed to get here become impassable after a storm.

|

|

|

|

|

|

On Independence Day everything is closed. With no festivities to attend, we are trundled out to the middle of nowhere to visit the Abaarso School of Science and Technology, recently the subject of a 60 Minutes story. It was started and is funded by an American hedge-fund guy to give a first-class education to promising youth. The curriculum is entirely in English, teachers are volunteers from numerous countries, and many graduates have gone on to prestigious US colleges. On the walls are inspirational quotes from such famous Somalis as Vince Lombardi and George Lucas.

In Somaliland, as in much of the region, the main interest and activity is chewing khat, cuttings from a shrub whose leaves produce a mild narcotic effect. Since alcohol is forbidden by Islam, khat is the recreational substance of choice in the Red Sea region. It is flown in daily from Ethiopia and distributed while still fresh (day old is no good). Only the men chew (someone has to do the work). The typical man’s day consists of waiting for the khat to arrive, finding money to buy it, and spending the rest of the day slowly chewing the leaves and gazing blankly. Khat stands are ubiquitous; competing "brands" are identified by three-digit numbers. By the end of the day heaps of discarded stems litter the ground.

|

|

|

With nothing else on the agenda, we chip in for two giant bundles and spend the afternoon in a typical Somali fashion. Our hosts are perfectly content, but our conclusion that chewing khat is as much fun (and about as effective) as chomping on garden weeds.

|

|

|

Hargeisa lies on a plain at an elevation of 4,000 feet, making the climate hot but tolerable. We descend to sea level for an overnight visit to the port city of Berbera, where the daily temperature regularly exceeds 100° accompanied by high humidity. The distance is only a hundred miles but poor roads dictate that the trip take over three hours (without AC). When we arrrive in the afternoon it is too hot to do anything except go to the beach. The waters of the Gulf of Aden are very warm (about 90°); those women who venture in do so in full cover-up garb (no burkinis here). At five o'clock the police arrive to clear the beach. The reason is "security", but I can't tell if the fear is of seaborne invasion or of people escaping.

|

|

|

Berbera sustained major damage in the war preceding independence, and little has been rebuilt since.

|

|

|

|

|

Although the town has seen better days, it has a certain colorful charm.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our hotel (a total dump, but at least the rooms have AC) looks out over the harbor and sunken ships that fell victim to Somali bombs some twenty-six years ago.

|

|

|

Our Berbera itinerary is severely curtailed. The scheduled boat ride is scrubbed because the entire port area has been declared a military zone. The UAE (Dubai, etc.) is building a naval station, which is a BIG deal because it is a major step towards international recognition of Somaliland as a sovereign country.

|

|

|

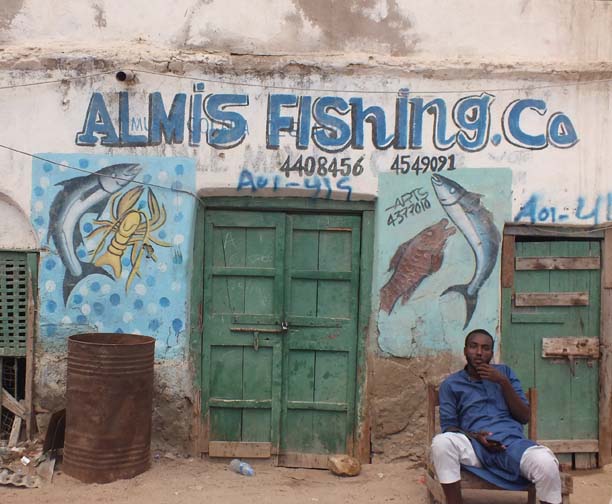

Besides the port, the principal economic activity of Berbera is fishing, which is what is for dinner.

|

|

|

|

|

The need for a permit for something or another takes us to the police station. On a pedestal in front is a fake-looking missile. We snap a couple of photos of it, which creates a major incident. The tour leader goes in to apologize on our behalf. Not good enough. We all have to troop into the commander's office to get a lecture about photography prohibited in such sensitive and secret places (which must be why they put placed it right by the road). Then his aides inspect each of our cameras to make sure that the offending image has been deleted. I show that my phone camera is clean (having already stashed my main camera back on the bus).

|

|

|

Before heading back to Hargiesa we drive into the hills to visit the small town of Sheikh. There is nothing special here, but it’s a chance to see life outside the big city.

|

|

|

|

|

That’s it, the week is up. On to Eritrea. If there were a direct flight, it would take just over an hour. Because there isn't, we need to return to Dubai, requiring more than seven hours of flying time and over twenty hours in total.