Enslaved Persons

|

It’s been awhile since I’ve been someplace new; West Africa fits the bill. No large animals to be seen – they were all eaten ages ago. You go to the former Slave Coast for history and culture. I come up with a intinerary that covers four former colonies from four colonial masters. My buddy Lou, who has never been to Africa at all, wants to knock it off his bucket list.

Delta flies non-stop to Accra, so Ghana first on the list. There is not a lot to see or do in the city, but I have allowed a couple days here to get the visas needed for when we reach the border.

|

|

We hire a car and guide for a city tour. The oldest part of the city is Jamestown, clustered around 17th century British and Dutch forts. The beachfront is home to hundreds of small wooden fishing boats, while the shore is a teeming, odiferous behive of activity loading, unloading, launching, mending nets, and drying fish.

|

|

|

A climb up the lighthouse affords a panoramic view.

|

|

|

Nearby is Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park, containing the masoleum and museum of the first president of Ghana who led the British colony of Gold Coast to independence in 1957. Until his one-man rule ended in a military coup, his crackpot socialism and corruption transformed a prosperous colony into a beggar nation, a pattern to be repeated across the continent. Nonetheless, he is lionized here and across the third world.

|

|

|

Unique to Accra are the fantasy coffin makers. A tradition of the Ga tribe for chiefs and priests, their production and use has become democratized; now, custom coffins are produced for anyone who can afford it. Generally, the coffin reflects the former occupation of its occupant: perhaps a pilot, a fuel tanker driver, a photographer, a pineapple grower, or a fisherman. Each one is the product of a skilled artisan and is unique.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By the third day we have seen the city, gotten our visas, and are ready to begin our tour. I have hired a sturdy yet comfortable Mitsubishi Pajero and Ben, who will be our driver, guide, and translator for the coming two weeks. (In addition to English and French, he seems to know all the local languages.)

We proceed north for about 80 miles to Cape Coast, the center of colonial administration until 1877 when the capital was moved to Accra. The town is built around Cape Coast Castle. Originally built by Sweden, then taken over by the Dutch, and finally captured by England, it was the largest of approximately 40 slave forts built by the European powers along the West African coast. The entire regional economy revolved around the capture, collection, and shipment of slaves to the new world. Unlike the fake slave-tourist mecca of Goree Island in Senegal, this place is the real deal.

After the abolition of the slave trade, the buildings were used for various government purposes until the Castle was restored as an historic monument. Admission includes a tour which seems primarily intended to induce a sense of guilt among white visitors to keep the aid the money flowing. And you are not supposed to say "slaves" anymore: the politically correct term is "enslaved persons."

The forts contain barracks for the troops stationed there, offices for the governor and officials, chapels, holding cells for the slaves awaiting shipment, even worse cells for the rebellious and condemned, and the “door of no return,” beyond which the slave ships awaited to receive their human cargo.

We stay at beachfront lodge a few miles further up the coast at El Mina, site of the oldest and largest of the Portuguese slave forts. Dating from 1482, El Mina Castle is the oldest European building south of the Sahara. The Dutch seized it in 1647 and continued its intended use. In 1814 the territory was taken over by the British in 1814. As the Brits did not need a second slave collection center so proximate to Cape Coast Castle, the fort fell into disuse.

|

|

|

Below the walls of the castle is a lively fish market that supplies our dinner.

|

|

|

We head inland to Kumasi, capital of the Ashanti kingdom. Along the way we stop a cottage industry that melt old bottles into colorful and attractive glass beads.

|

|

|

Another stop at “Slave River”, where captives from the interior got their last bath before being sold to the coastal castles. This time of year the stream is barely a yard wide

Terms of royalty are used loosely in Africa: most “kings” were tribal leaders and most “kingdoms” were comprised of tribal groups rather than a defined geographic area. The usage is less stretched when speaking of the Ashanti: as early adopters of firearms, they prospered selling captives to the slave traders.

The Ashanti kings maintained an inland empire from 1791 until modern times. The current, modern royal palace is not open to visitors, but the 1925 version is now a museum. Displayed alongside various tribal artifacts are a collection of the personal acquisitions of the royal family from the 1920’s through the 1960’s, mostly furniture, firearms, radios, and other consumer goods from Europe. (Unfortunately, no photos allowed.)

Our base is the Kumasi Catering Guest House, reputedly the oldest hotel in Ghana, Set on spacious landscaped grounds in the center of the city, the place oozes character. The rooms are attached bungalows, large and comfortable if not particularly modern, with bathrooms eligible for their own zip codes.

Across the street is the Kumasi Fort and Military Museum. First built in 1820 in imitation of the European coastal forts and rebuilt after being destroyed by the British in the Ashanti Wars, it now mostly chronicles the exploits of the Gold Coast Regiment. Deployed in WWII against the Italians in Ethiopia and thereafter to Burma, they brought back a fine collection of Italian armor and other souvenirs. One room is devoted to the short campaign against neighboring German Togoland in 1914 (more on that later).

We also visit the Kumasi Cultural Center, a tourist village showcasing native crafts. A total bore: the stuff is of low quality and minimal artistry. A bit better is a drive to outlying villages where cloth is block-printed and where Kente cloth is woven.

|

|

|

From Kusmasi we drive to Atimpoku on the Volta River. The river was dammed in the 1960’s creating Lake Volta, reportedly the the largest man-made lake in the world. The waterfront lodges are within weekend driving range of Accra, but quiescent during the week. A pleasant place to stop for the night.

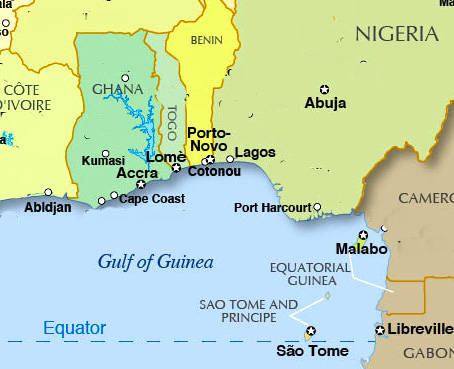

The next morning we cross the Volta. We are still in Ghana, but this used to be the border between Gold Coast and Togoland. In 1914 in the first week of WWI the British and French seized the undefended German protectorate of Togoland and divided it between themselves. What was christened British Togoland was incoporated into Ghana; French Togoland became the country of Togo.

The paved road ends and we proceed towards the border. The border post is comically small, consisting of twin shacks on either side of a symbolic gate. One can see that much of the duty officers’ day is spent snoozing on tree-shaded cots, but they wake up to stamp our passports out of Ghana and issue visas for entry into Togo.

|

|

|

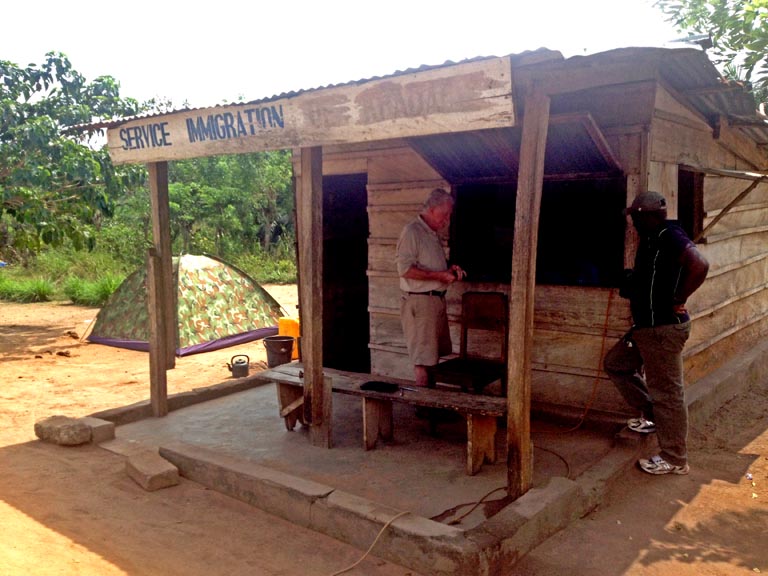

Togo is much poorer than Ghana, On either side of us is typical African rural scenery and village life. Those who are not on foot are on motorbikes, refilling from roadside stations where fuel is sold in bottles and flasks.

|

|

|

|

|

We reach Kpalime just after lunch and check into Chez Fanny, a hostelry owned by a very proud expat from Normandy. The accommodations are modest but the food is superb. We visit a nearby waterfall and stop in the market where I make my first purchase of African print cloth to be made into shirts.

|

|

|

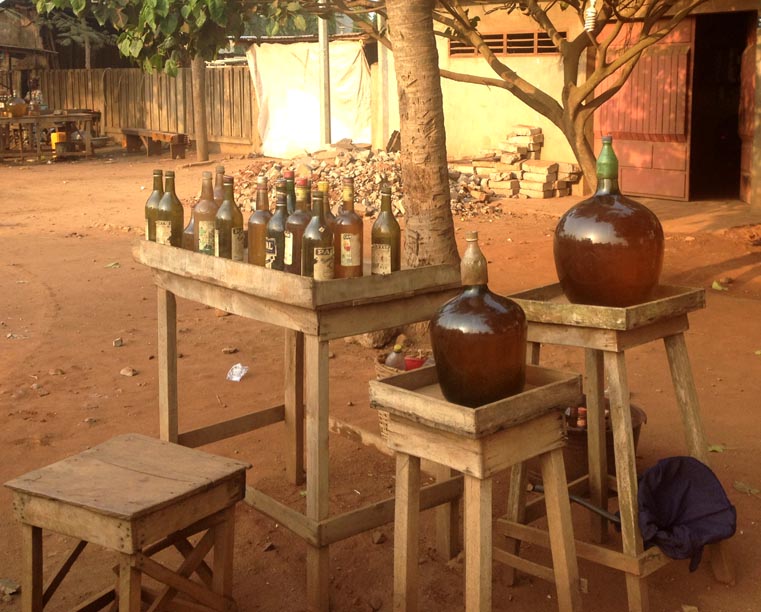

Togo is quite narrow. It does not take long to reach our third country, Benin, the former French colony of Dahomey. We drive to Aboumey, the capital of the Dahomey kingdom. Each hereditary king built a separate palace adjacent to his precedessors; the complex of eleven palaces now a World Heritage Site. Being made of mud brick and thatch, most are in pretty poor condition but a couple have been restored as a museum.

|

|

|

|

|

Just outside of town is an underground village where the inhabitants hid from slave raiders. It was in the middle of dense forest and remained undiscovered until recently.

|

|

|

|

|

We drive back to the coast and to Porto Novo, the capital of Benin, close to the border with Nigeria and only about sixty miles from Lagos. There are a few places of interest: a cathedral built in Afro-Brazilian style; a giant statue of a Dahomey king; a few colonial-era buildings.

|

|

|

We skip the Ethnographic Museum in favor of the da Silva Museum, housed in the mansion of a descendant of slaves who returned from Brazil to the land of his ancestors. Inside is an ideosyncratic assemblage of his cars, his junk, stuff he collected, odd photographs, and stuff he found interesting. One room is full of old radios, another of cameras, still another of souvenirs from various trip to other countries. Defying explanation is a gallery of hundreds of unlabeled photographs of personages such as Gandhi, Himmler, and Stalin.

Drving on, we pass through the the modern, ugly, port city of Conotou, the commercial capital of Benin. We are on our way to Ganvier, a stilt city in the middle of Lake Nokoue orignally settled by those fleeing slave raids.

|

|

|

A boat takes us from the dock through the village to our hotel, where we are the only guests. A generator supplies light in the evening hours, but there is no AC or wifi. Good thing we are only staying for one night.

|

|

|

The current population of around 20,000 conduct their entire lives on the water. A principal occupation is fishing, although the few patches of dry land support a few vegetable gardens and a bit of animal husbandry. Occasionally a giant canoe passes laden with hundreds of fuel containers: they are smuggling fuel stolen from pipelines in Nigeria.

|

|

|

On Sunday morning the canoes are filled with villagers in their brightest prints paddling to stilt churches.

|

|

|

|

|

On to Ouidah, where our reward for roughing it one night is two nights in a modern beachfront resort hotel.

|

|

|

Ouidah was the Dahomey's main port until eclipsed by Contonou. In the center of town is a 17th century Portuguese fort which was maintained as a foreign outpost by that country until 1961. There is not much else other than an outsized Basilica and a voodoo python temple.

|

|

|

|

|

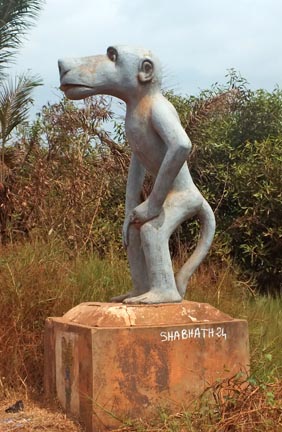

Totemic sculptures line the road to the beach, now dubbed the Route of the Slaves.

|

|

|

|

|

Not far from our hotel are huts used by locals to distill salt from brine.

|

|

|

As pampered tourists in the tropics, we drink only bottled water. From Ouidah we drive to Possotome, located on Lake Aheme and the source of the eponymous bottled water. Nothing special here, just a nice resort featuring waterfront bungalows.

|

|

|

Just up the road is a tailor who stays up all night transforming my cloth into half a dozen beautiful bespoke shirts.

|

|

|

It has been more than a week since we first entered Togo, and our seven-day visas have expired. To go back requires obtaining another visa, again issued at the border. We drive to Togoville on the shores of Lake Togo, where in 1884 the king of Togo signed a treaty accepting a German protectorate.

|

|

|

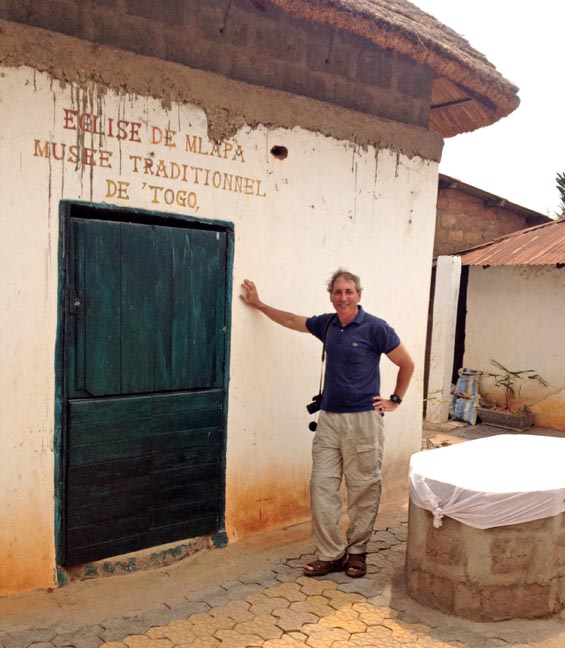

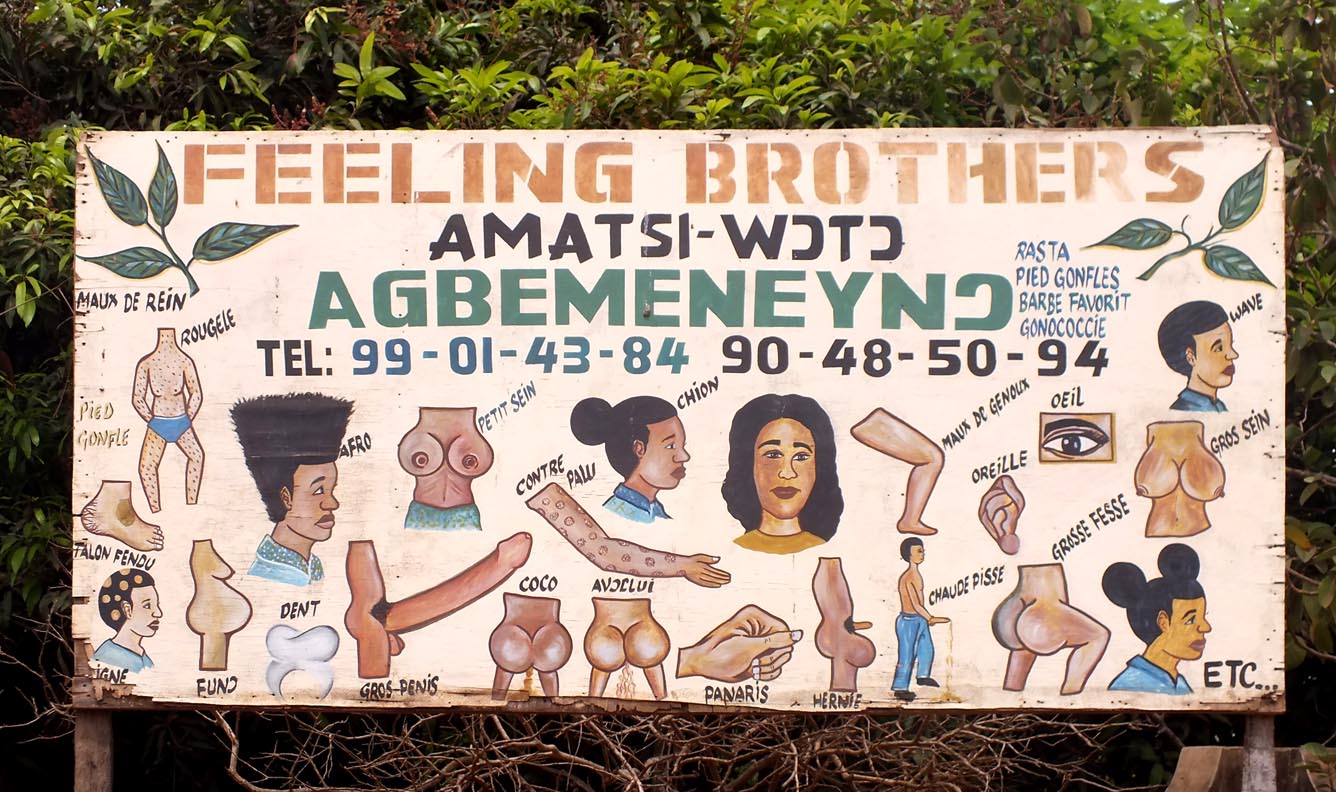

The largest building in town is the German-built cathedral. Considerably less impressive is the royal palace, a compound where the king’s extended family resides in a standard not far above his hardscrabble subjects. We enter, expecting an audience with the king’s son. Instead, we meet his assistant and are treated to a lengthy diatribe on how poorly they are treated by the government and how good things were when the Germans were here. But least they have Obamacare:

We continue on to Lome, the capital. On one side of the highway is an attractive beachfront, but little else of interest. The busy market yields a couple more bolts of cloth for future tailoring.

Our two weeks is up, Ben drives us back over the Ghana border to Accra and takes us directly to the airport. The second part of the trip is about to commence. Lou declares that it’s been a great trip but he has had enough Africa; he cuts short his itinerary and heads back home, taking the plane to New York while I board another to the final country on the tour.