|

|

Russia Part 2

The Far North |

|

And now for something different.

Norilsk is the world’s northernmost city (<100,000), lying 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle. It is a closed city, forbidden to foreigners except by permission of the F.S.B. (successor to the K.G.B.). Before we are allowed to board the flight, our permit is carefully checked.

It’s a three and a half hour overnight flight from Moscow, passing through 4 times zones. (The further you travel from the equator, the thinner the time zone “wedges” get.). We land in daylight. This time of year, it is always daylight: the sun has been up almost two months and will not dip below the horizon for another two weeks. (The downside is that in winter the polar night is equally as long.). It is 52° with a whipping wind, but the locals getting off the plane are dressed for a day at the beach. At the arrival gate, those carrying Russian passports are waved through; we are herded upstairs to the security office for processing. It is a reunion of sorts: all of us are Koryo veterans, and I recognize many in the group (we are 18) from Kazakhstan last year and prior trips.

We stop just outside the airport for a group photo in front of a sign letting all know that this is the Taymyr Peninsula. We are approximately 30 miles distant from the city, but our initial destination, Dudinka, is in the opposite direction.

Dudinka is located near the mouth of the Yenisei River, one of the three great rivers of Siberia flowing north to the Arctic. Founded in 1667 as a trading settlement, it is the port city for Norilsk as well as a vast region to the south. In the absence of roads, it is a vital transport link.

The town has a compact Soviet design. The main square faces the water. There is a statue of Lenin; behind him is a theater/concert hall (Dom Kulturi, “House of Culture”). To one side is a regional museum. A recent addition is a Russian Orthodox Church. The obligatory war memorial with requisite tank is close by.

|

|

|

|

|

Were things left to nature, the port would be open only a couple weeks of the year. Nuclear-powered icebreakers extend the shipping season greatly. Due to huge ice accumulations (20 meters, 65 feet), the dock facilities are dismantled each winter. In early July there is still a fair bit of ice still stacked up.

|

|

|

This is not exactly a tourist hotspot, so the only place to stay is the Yenisei Hotel, a simple but adequate hostelry, part of an all-purpose building that houses mostly offices. Other non-descript structures are configured as apartments.

|

|

|

For such a small, remote city, the museum is quite good, covering natural history, ethnography of the indigenous Samoy, and local history. That's a real, freeze-dried mammoth.

|

|

|

|

|

Then, a special welcome from Father Frost and his Ice Princess. Each of us is awarded a "Diploma," kind of like the Scarecrow getting one at the end of The Wizard of Oz.

|

|

|

Next, we get a hands-on lesson by a local Samoy in preparing a local delicacy, slicing frozen fish into sashimi (but they don’t call it that). You are supposed to pop it it in your mouth before it thaws and follow it with a shot of vodka. Palatable, but probably better when done in winter.

|

|

|

|

|

That night, we get our first experience of the midnight sun.

|

|

|

|

|

The next day we follow the road (there is only one road) back past the airport to Norilsk. On the way, we stop for a brief wander through an abandoned factory complex.

|

|

|

You can tell we are approaching Norilsk by the belching smokestacks. It has the dubious distinction of being the most polluted city in Russia, mostly due to sulfur emissions from the smelters.

|

|

|

The city is here for only one reason: to exploit the world's largest nickel/copper/palladium deposit. It was built under Stalin in the 1930’s as one of the most notorious parts of the Gulag; its workforce consisted largely of an expendable and continually replenished supply of prison and slave labor. Post-Stalin, workers were "volunteers" who enjoyed better wages and benefits to compensate for the hardships.

|

|

|

We check into the Hotel Norilsk, a quite comfortable lodging deserving more than its two star rating. The entrance is not particularly welcoming — like all buildings in the city it is designed to keep out the -30° winter cold, with a series of vestibules before one reaches the lobby. Even the outside smoking area is fully enclosed.

In the afternoon, a walking tour. The main drag is the Leninsky Prospect. Residential and commercial buildings extend several blocks deep on either side; after that, the tundra begins. A combination of soviet design and climactic necessity impart a sameness to the buildings. Even the shopping centers are hidden behind the uniform facades. The exteriors are painted in bright pastels as a measure to combat depression during the long polar nights.

|

|

|

|

|

The city prides itself on its level of culture. Under Stalin many artists and intellectuals were sentenced here. Their legacy includes the Polar Theater.

These days, no one is forced to live here. Workers are drawn by relatively high pay. Miners and other workers from the Muslim republics of the former U.S.S.R. have built the world’s northernmost mosque. This being post-Soviet Russia, there also churches.

|

|

|

The mining operation has been privatized. The owner and operator is Nornickel (formerly Norilsk Nickel), a Russian company with operations in Europe, Australia, and Africa. This is definitely a company town.

|

|

|

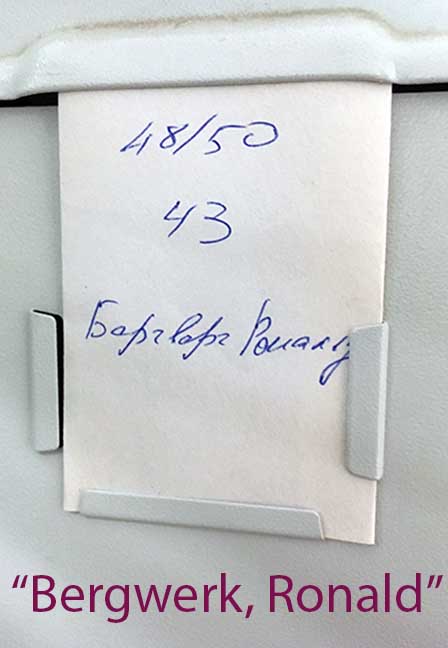

And we get to be trainee miners for a day! A played-out mine on the edge of the city is now utilized for training purposes. Our measurements were previously transmitted to the company, which thoughtfully has provided us with personalized lockers containing our mining gear. After suiting up, we watch a safety video (in English). Then, a quick medical check for fitness. We were warned last evening to abstain from alcohol, because to unlock the final gate one by one each of us must blow into a breathylizer.

|

|

|

|

|

We take the elevator down into the shafts. There is brief lecture in an underground classroom, after which we we enter the excavated caverns where various items of equipment are demonstrated. Although we are laden down with safety gear, including a “self-rescue” kit, no cameras or other accessories are permitted, so the only photos are topside.

|

|

|

Current mining activity has moved to Talnakh, about 20 miles east., at the far end of the road that begins in Dudinka. Outside the city it’s all taiga. We cross the Norilskaya River, stopping at a health sanitarium to see their bear.

|

|

|

A plentiful supply of lumber (and a dearth of other materials) makes for unusual plank insulation on miles of pipeline.

This is no flying visit — we have actually packed up and checked in to the Hotel Talnakh for the night. It being a newish, satellite city, the attractions are more scenic than historic.

|

|

|

|

|

There are no Lenins in sight, but for lovers of outdoor art Talnakh does not disappoint

|

|

|

|

|

Until Disney opens a theme park, there is a fun junkyard in which residents can frolic.

|

|

|

|

We drive back in Norilsk for our final day. What we have seen so far is the Khrushchev-era city. Immediately adjacent is the largely derelict Stalin-era city. Rather than update obsolete industrial facilities in the heart of the city, new ones were constructed at its edge. Workers' dormitories and communal flats were replaced by individual family apartments. Even the old central plaza was abandoned

|

|

|

To get the refined nickel and other ores out, a rail line to the port of Dudinka was opened in 1937.

Stalin wanted to extend the tracks to the “mainland” (i.e., the rest of Russia). In anticipation, a rather grand railway terminal was built. After his death in 1953, the project was abandoned. The station is now a museum run by the benevolent Nornickel.

|

|

|

|

|

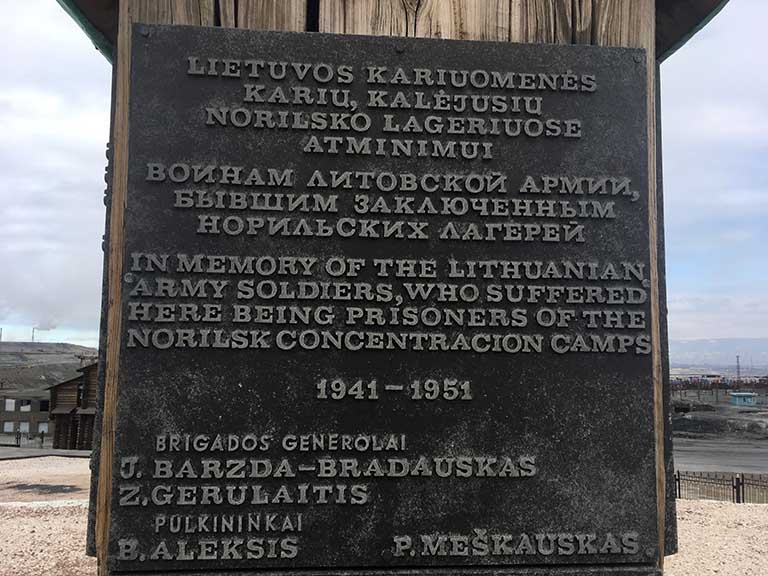

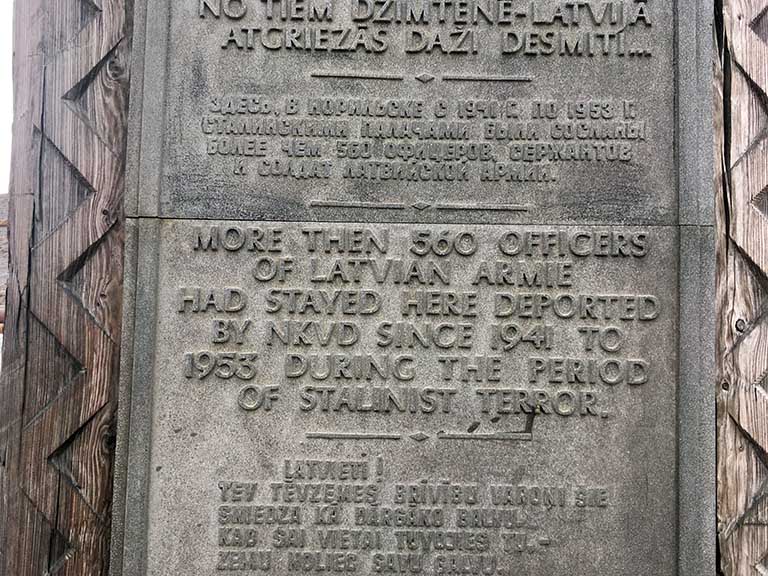

In addition to metals, Norilsk and its harsh conditions produced plenty of corpses. These were buried in an area known as “Golgotha.” In the post-Soviet era a number of memorials have been erected to the victims of the Gulag. In terms of prisoners sent here, it seems that the Baltic states were particularly well represented.

|

|

|

|

|

Despite that somber note, it is a festive final evening. It has been an excellent trip. At a lavish farewell dinner, the challenge is put forth to Koryo: next year, even wierder and better!

Trip date: July, 2019