The Garden of Eden

It’s taken me twelve years to complete my Axis of Evil Tour: Iran (2001); North Korea (2007 and 2010); and now, finally, Iraq.

Tourism-wise, Iraq is open for business, although the word is not exactly out. The guy who runs Hinterland Travels (with whom I went to Pakistan) has been leading tours to these parts for 30+ years. I have signed up for the full-length tour: top to bottom in three weeks.

The joining point is Diyarbakir in eastern Turkey, reach by an internal flight from Istanbul. This where the grandson of Genghis Khan stopped to recharge before conquering Baghdad; I hope to do the same. Our group is eight: Brits; Aussies; a Mexican; and me, plus our British leader.

I leave Jacksonville on Sunday, September 1st, arriving in Diyabakir on Monday night. We have the next day to explore the city. Although the tourist board is trying mightily to sell this place as a tourist destination, it doesn’t look particularly different from other Turkish cities. The populace is Kurdish, but that identity has been strongly suppressed by the government in Instanbul. There are a couple of restored churches from the now largely-departed Armenian minority, some mosques, and several old bridges spanning the Tigris. The dominant feature is the black basalt city walls, which work crews are busily restoring. Are they getting ready for the next Crusade?

On Wednesday, September 4th, the trip begins. We have a minibus to take us further east, following the Syrian border for much of the route. Half a million Syrian refugees are in Turkey, many living in camps on the outskirts of border cities. Diyabakir is said to have its share, though I don’t see any in the historic walled city.

Something strange: when we reach Silopi our bus pulls onto a ramp and a guy gets underneath to drain fuel into a pan. Other vehicles adjacent are undergoing the same procedure. My guess is that they will fill up on cheap fuel in Iraq, smuggling it back into Turkey.

“Welcome to Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government” proclaim the signs greeting us upon crossing the border. There is no indication at all that we are entering the country of Iraq; Kurdish flags fly everywhere. Imposition of the northern “no-fly” zone following the 1990 Gulf War enabled the ethnically, culturally, and linguistically distinct Kurds to hive themselves off from Saddam’s regime in Baghdad. They brand and market themselves as “The Other Iraq.”

Kurdistan also controls its own borders: although we have a visa authorization from the Ministry of Tourism in Baghdad, it matters not here; the KRG issues its own visas. Visas on arrival are freely given to citizens of western nations; other nationalities, such as Bangladeshis, are barred. (They also keep out Arabs – including Iraqi Arabs – which is why Kurdistan is safe.) Unfortunately, Mexico is not on either list. It takes almost two hours for permission to be received for our entire group to enter.

Our immediate destination is Dohuk (located, confusingly, in Duhok Governate), a city of almost a million inhabitants. . (According to Wikipedia, it is a sister city to Gainesville, Florida, but I see no evidence of Gator anything.) There is not much to see here, but it is our base for excursions the next day.

Thursday morning we visit a Yazidi village. The Yazidis are an ancient religion, monotheistic but pre-Christian. Satan (represented by a serpent) is an important figure in their cosmology, so they are frequently derided as devil-worshippers. Their principal shrine is in the village of Lalish, which we visit next. Hard to describe, but very interesting. Like Muslims to Mecca, there is an annual pilgrimage to Lalish that the faithful must undertake it at least once in his life.

> >  |

Although the landscape is hilly and brown, the soil is fertile. The region was able to support great civilizations – this is the heart of Assyria – but, of course, that was before global warming.

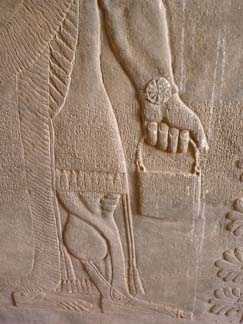

Our final visit of the day is to the cliff-side relief sculptures at Bavian Gorge. Sennacherib, the Assyrian king whom the Bible records as conquering the northern kingdom of Israel, carrying off the 10 “lost” tribes, and then besieging Jerusalem, dug a canal to water his capital at Ninevah. On a cliff overlooking the waterway are carved monumental reliefs of the king and his gods. (The defacing holes are believed to been hewed by early Christian hermits.)

After a second night at Duhok we drive to Halabja, site of the poison gas attack for which Saddam Hussein and his henchman, “Chemical Ali”, were hanged. During the Iran-Iraq war Saddam unleashed chemical weapons on the Kurdish village, killing an estimated five thousand. There is a large monument, closed for the moment for remodeling. At the entrance to the cemetery where the dead (mostly women and children; the men were off fighting Saddam) are interred in mass and individual graves, there is a sign: “Baath Party Members Not Allowed To Enter.”

Parliamentary elections are coming up, and the campaign is in full swing: every city, town, village, and street is festooned with banners. The posters depict a number of female candidates, all of whom appear amply nourished.

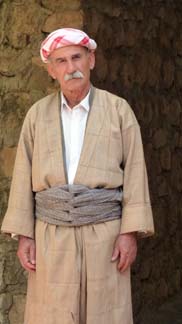

We spend the night in Suleymayah, Kurdistan’s second-largest city, where I venture into the market and acquire traditional garb.

Saturday we move on the Erbil, the capital and principal city. Like Suleymayah (and very much unlike what we will encounter in Iraq proper), it is clean, orderly, prosperous, and safe. Kurdistan exists on a revenue-sharing basis for its oil exports, which now can only be shipped out to the south. A pipeline to Turkey is under construction; when that is complete, look for even greater Kurdish separatism.

We stay at the Erbil Towers Hotel, which offers poor design, shoddy construction, laughable décor, lack of maintenance, and soviet standards of service, all at stratospheric prices. (There are some new five-star hotels at even more astronomical cost.) Our hotel does offer an excellent location overlooking the Citadel.

The Citadel is an acropolis (literally “high city”) built, like the one in Athens, on a flat outcropping. It claims to be the oldest continuously-inhabited city on earth. Within the walls is a huge renovation/restoration site. There are plenty of guards to tell us where we can’t go, but no other visitors and no inhabitants, since UNESCO requires as a condition for world-heritage money the eviction of all residents. (So much for “continuously-inhabited.”) White Toyota Land Cruisers with blue plates, the official vehicle of the international parasite NGO/Quango class, are ubiquitous.

We are also the only visitors in the Erbil Civilization Museum. The collection is a lot of nothing, the great finds in the region having long ago been shipped to London, Paris, and Baghdad. On display are unadorned bits of broken pottery and other detritus, and a few chipped plaster copies of good stuff (c’mon guys, at least get out the shoe polish!). Students from America are beavering away on fresh buckets of broken pottery from a current dig. Right behind the museum is an actual tel (archeological mound). In the absence of a gift shop, at the least I expect to be issued a shovel so I can find my own souvenirs.

Erbil is the first place we encounter the Iraqi flag: flying next to the Kurdistan flag in front of Parliament. Americans are well-liked here (as in the rest of the Kurdish regions of Turkey, Iran, and Syria) – there is even a Hotel Washington. By the way, the citadel is not the only sight in Erbil: there is also the stub of a 12th century minaret.

Our time in Kurdistan is an extension of the regular Iraq tour, and thus far we have had ad hoc transportation arrangements. In Erbil we are met by our bus up from Baghdad. Besides the driver, there is a guide/interpreter from the Ministry of Tourism and a police captain assigned from the Ministry of the Interior. All will be with us full time for the remainder of the trip, not as minders but for our security.

On Sunday we venture outside the KRG security zone. At the checkpoint we are met by two truckloads of heavily-armed police who will be escorting us for the day. When told that we would like to like visit Ninevah, the ruins of which lie on the outskirts of Mosul, a heavily-contested and most-dangerous city, the guy in charge responds with a “what, are you crazy?” look of shock. No Ninevah for us.

We do get to go to Nimrud, one of the three, at varying times, capitals of Assyria. (The other, Assur, is also in a no-go zone.) A (literally) wonder-full site/sight, no other visitors.

Our mini-convoy moves on to Mar Benham monastery, built in the 4th century as a act of penance by an Assyrian king. He beheaded his son, Benham, for converting to Christianity, but later he himself converted. Benham was canonized, and his tomb/shrine became a pilgrimage site.

High in the nearby mountains is the fortress-like monastery/shrine of Mar Matti, who converted Benham. It, too, dates from the 4th century. Both are run by the Syriac Orthodox Church, one of several ancient Christian sects in the middle east. Rather than Latin or Greek, their liturgical tongue is Aramaic, which was Jesus’s second language (after English).

The head of our security detail, on learning that I am American, asks me about “Langlee. Military wall names.” I finally figure out he is talking about the Wall of Honor at CIA headquarters where stars commemorate anonymous fallen spies. Now on topic, he proclaims himself an expert on the CIA, having seen all the Bourne movies, even the fourth one which “was not very good.”

On Monday we leave the KPG enclave and enter wild and wooly Iraq. Another forced miss for security reasons is Hatra, the Roman-era archeological site where the opening scene of The Exorcist was filmed.

Thus, I am a bit surprised that we take lunch in Tikrit, Saddam’s hometown. His palace on the banks of the Tigris can be seen from the bridge, but no stopping allowed. During lunch there is a power outage. I am sure the other diners were thinking “This wouldn’t have happened in Saddam’s day.” Tikrit did quite well under Saddam, and this is no place to be flying an American flag. We are not allowed to wander at all. On the way out of town we glimpse his tomb, but the road is blocked off to keep away would-be pilgrims (them) and the curious (us). In the vicinity is the spider-hole where he was captured.

We have an appointment in Samarra. This is one of the oldest cities in the world (yes, there are a bunch that make that claim), and it was briefly, in the 9th century, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate. The first stop is the “Lover’s Palace,” impressive from the outside but not much inside. The story is that it was built as a form of prison for a disfavored wife or princess.

When we are done, we have to wait for second truckload of police before proceeding to the Spiral Minaret. When we arrive we encounter what will become tiresome scene: although we have written authorization to enter each place on our itinerary, whoever is in charge there doesn’t want to let us in for some invented reason or no reason at all. After some posturing (and sometimes a bit of baksheesh), the situation is usually resolved.

The minaret accompanies the Great Mosque, now disused. From the top we can see the chemical plant next door where Saddam played cat and mouse with UN inspectors who regularly came looking for WMDs and the golden dome of the mosque/shrine of the 10th and 11th imams. The latter is a major Shia holy site and pilgrimage destination. The dome and twin minarets were toppled by bombs in 2006 and 2007, setting off the wave of sectarian violence that led to the Surge. The mosque has been rebuilt, but negotiating the ultra-tight security would require more time than we have.

We do visit what’s left of the Caliph’s Palace.

That evening we reach Baghdad. The first things we notice are the numerous checkpoints and the concrete barriers along the street to prevent access by car/truck bombs and to deflect any blast. They have been gradually removed from most commercial districts, but still are in front of all government and office buildings, sometimes stretching for blocks.

Our base in Baghdad is the Uruk Hotel: small, friendly, and comfortable, but a bit worn. We are greatly surprised to learn that it is only four years old.

Tuesday is Baghdad sightseeing day. Our first stop is the National Museum. Ten years after the invasion it’s still not open except by invitation, which we have. Or are supposed to have. Another half-hour of buck-passing and trying to find someone who will take responsibility. This is the place that got looted in the first days after the fall of Saddam. Everyone, including the looters, knows whom to blame: George W. Bush.

The museum is a good example of the full-employment society: a huge staff, no business, and no one actually working. Our guide is the director himself (I think), a personable guy with excellent English (I guess someone else is responsible for the “DO NOT TUCH” signs) and fascinating stories about how various pieces were recovered. He is accompanied by a staff photographer – I don’t know whether it’s his ego or the importance of our visit – and two shapely assistants in very tight clothing and headscarves to preserve their modesty.

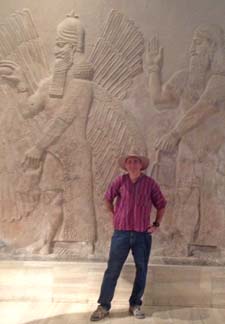

Unfortunately, the gold and jewels remain in the vaults of the central bank, but the stuff we do get to see is eye-popping, especially the galleries of Assyrian reliefs. Best of all, we have the place to ourselves.

It takes forever to get anywhere in the city. It seems like every few blocks we are stopped at a checkpoint and our papers and passports examined. We are told that there is an alert concerning foreigners; no need to be so general, we are the only tourists in the country! Even stopping for a photo of the empty plinth where Saddam’s statue was pulled down causes major consternation. Then I glance down at my watch and see the date: September 11th.

Baghdad is an old city, but not an ancient one: it was founded in the 8th century and destroyed by the Mongols in the 13th. Sights within the city are sparse. There is an old madrassa, and old mosque, and a renovated caravanserai. The train station is one of the last things built by the British in a neo-imperial cum art deco style; its ticket windows are still labeled for Syria, Turkey, and other long-ago destinations. Inside the office are plans and models for a network of bullet-trains that will forever remain a pipedream.

Outside the city, there is quite a bit to see. There have been numerous and continuous civilizations in Mesopotamia, more than are mentioned in the Bible or we remember from high-school textbooks. One was the Kassites, a Babylonian dynasty that peaked around 1300 B.C. We set out Thursday morning for Aqar Quf, the modern name for a Kassite site. What remains above ground is the core of the ziggurat; the lower level has been reconstructed. A popular picnic spot, the site has just reopened after ten years; it was off-limits because the road leading to it also goes to Abu Ghraib, home of the notorious prison.

In the afternoon is the Ctesphion Arch, the largest brick arch in the world, part of the remains of the grand hall of a 6th century Persian palace. Unfortunately, the sun is in the wrong position for photographs. (This oughtta be our morning stop.)

Nearby is the tomb/shrine of Salman Pak, Mohammed’s barber. This is a long way from Arabia – I wonder what he was doing up here. Perhaps a visiting professor at a local barbers college?

Friday, the 13th, we move south from Baghdad. First we visit the site of Kish, which mounds are what is left of a city from 4000 B.C. I guess it was considered a desirable place to settle because homeless Kishites could live under a neaby overpass. On the way up the ziggurat, where the mud bricks and woven matting are still visible, I find a tin can from the royal pantry (butter beans). However, I suspect that the Coca-cola can might not be completely authentic.

More impressive is the ziggurat at Borsippa. Long (mis)identified as the Tower of Babel, it was built by Nebuchadnezzar using millions of fired and unfired bricks. Opposite is Abraham’s favorite mosque, or where he stopped as a baby, or something.

On to Babylon! The royal palace has been extensively reconstructed, or, as our local guide repeatedly emphasises, “Saddam did not rebuilt Babylon, he destroyed it.” The original bricks in the walls are stamped with the seal of Nebuchadnezzar; the new ones bear the name of Saddam.

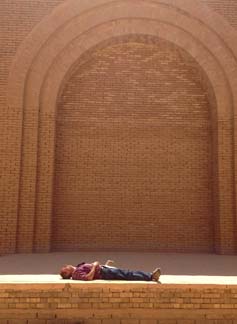

We start at the Ishtar Gate, recreated in 2/3 scale. (The original is in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.) The original blue glaze was made with ground lapis from Afghanistan . The platform in the throne room is the exact spot where Alexander the Great died, a scene that I reenact for the camera.

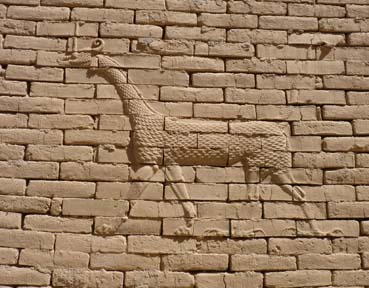

Along the processional way are brick reliefs of mythological animals.

Just outside the rebuilt walls are the unrestored parts of the city. These look like piles of mud bricks, just like we have been seeing everywhere else. Historic and aesthetic criticisms aside, the recreated Babylon helps the visitor to envision what it must have been like.

On a hill overlooking the ruins of ancient Babylon are the ruins of the modern palace of Saddam. Although he rarely strayed from Tikrit or Baghdad, he had dozens of palaces all over the country. They are now used by the government and closed to the public, but the one here was looted and abandoned. Everything that can be removed has been carted off. Still, the scale, if nothing else, is impressive. A couple of concrete relief panels on the outside walls contain the only extant public images of the former president.

The next day, Saturday, we start by stopping at the spring of Iman Ali (Mohammed’s son-in-law). It’s the spot where he miraculously found water in the in desert. On the hadj road to Mecca, it’s now a pilgrimage site. Unfortunately, it’s also closed for renovation.

We then visit the Neolithic cave complex at Al Tar. They were dug by hand in the late Stone Age. There being no cavemen about to photograph, I take a quick snap of the caves and await the return of the others, who wanted an up-close look.

More recent, and more interesting, is the 8th century fortress/palace of Ukhaider. Another World Heritage site. (Not exactly scare in these parts.) As usual, we have the place to ourselves.

;

;

Last stop is the ruin of the 5th century “Caesar’s Church” at Al-Aqiser. An archeological team hastily abandoned the site about five years ago, and their finds are in heaps all around. I think about nicking a colorful shard or two but don’t, not because of conscience but because they look like nothing ex situ.

Our base for two nights is the pilgrimage city of Karbala, site of the martyrdom of Hussein (grandson of Mo’) and his half brother, Abbas, and the home of their twin shrines/tombs. In the lobby of our hotel is a world clock map showing the time in all the important countries (if you are a Shia pilgrim): Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Bahrain, Turkey, and Qatar; the rest of the world is a blank.

Security is tight: the streets surrounding the shrines are blocked off, and all who enter are screened. Inside, there is a festive air: strings of colored lights, souvenir shops, refreshments. (I have a great idea for a souvenir: who could resist buying a set of shot glasses featuring Ali, Hussein, and the other twelve imams?) Women go in via separate entrances -- upon emerging one gal in our group exclaims “I have been to the Black Sea!”

Towers for the Imam Hussein TV Network (“All Hussein, All The Time”) loom overhead. Our Mexican friend quips, “You know the similarity between here and Miami? NOTHING!”

As infidels, we are not admitted into the shrine of Abbas. Next door, at Hussein’s, we luck out: after a bit of a wait we are ushered into an office and assigned a guide. I even get a press pass, allowing me to take photographs. (When I ask someone to take a picture of me, I have to hand over the press pass for the moment, and anyone who wants to take a picture has to borrow it.)

The inside? In a word, “sparkly,” as if designed by crows or magpies. It’s packed with the faithful: some in prayer, others in ecstatic group chants, still others just hanging out. People are reading, guys on high chairs are sermonizing. With our guide, we are able to pass through both the men’s and women’s sections. We even violate protocol and enter the inner sanctum containing the tomb of Ali. An excellent visit.

Sunday, September 15th, bad news from where we just were: multiple bombs in Baghdad and Hilla (near Babylon) have result on a large number of dead and wounded. One reason could be that the security checkpoints are equipped with “bomb detectors” that are nothing more than wands wired to a box of useless electronics. A Brit who sold them to the Iraqi government for $75 million was recently sentenced to prison for fraud – they are nothing more than repackaged novelty “golf ball finders.”

Our first stop of the day is al-Kifl, site of Ezekiel’s Tomb. The jerk in charge won’t let us in, citing safety reasons due to construction activity underway. Pretty damn cheeky of him, considering that the project is being funded by UNESCO. What’s really going on is that this was historically a Jewish shrine and village; the Jews are all gone, and the Islamists are now actively erasing any evidence.

We continue to Kufa, home of Ali. Another strike-out. We are not allowed into Ali's house. This area is the power base of the self-styled Mahdi Army, the Shia paramilitary force under the control of Muqtada (“Mookie”) al-Sadr. They are feeling their oats and making up and enforcing rules just to show they can. Posters and billboards of Mookie and his late father, Ayatollah al-Sadr are ubiquitous; the latter being greatly respected and the former just a firebrand.

The Grand Mosque of Kufa is also closed to us, but that bar has long been in place. We are graciously received the in head office, shown the calligraphic studio and given a demonstration. He gives us a nice brochure on what we can’t see: this was not only the mosque frequented by Ali – he lived next door – but it seems Noah lived here too.

The tomb of Ali is in Najaf, another major pilgrimage destination and our next. Roadside sign as we approach: “Najaf Welcomes Generous Guests.”

The city is one huge construction site. (Slogan: “bringing you a bigger and better Ali.”) Everyone wants to make like Ali, so Najaf is also home to the world’s largest cemetery. (Slogan: millions served.”)

The place is even sparklier than Karbala. We are allowed to visit the shrine and peek at but not enter the inner sanctum. As swarthy as I may be, I don’t exactly blend in. An Arab comes up to me and asks where I am from. He says he’s from Norway. “That’s funny,” I refrain from saying, “You don’t look Norwegian.”

September 16th: back from the medieval to antiquity. We visit Nippur, another Sumerian city. Scattered about are innumerable pottery shards. I look for one decorated with an erotic scene painted on it or perhaps with my name written on it (in cuniform, of course). No luck, but I do find a striped fragment in the Tel Ubaid style, named for the place it was first found.

The grandest city of the time (4000 – 3000 B.C.) and most extensive ruins now is Uruk. (Gilgamesh was the king of Uruk.) This is the only site since the Bavian Gorge that we must pay to enter. The sign says “Welcome to Uruk Ancient City. Ticket sales at this location.” By “this location” they mean some 40 miles distant. On site there is only a guy to collect the tickets. We bring along guards, who, from the way they pose for and snap pictures, have never been here. (True pretty much anywhere we go; Iraqis have little to no interest in seeing more piles of sand.) They are tasked with making sure we don’t nick anything, but by this time we are are potteried out (Although, for the $20 entry charge, they could let each visitor take home a bucketful and still NEVER run out.) What would be worth stealing are the blue lapis glazed bricks that form a wall in one of the palaces. Also on the site is a Greek/Parthian temple that is “only” 2000 years old.

Less well know than Uruk but even older is Eridu. There’s not much left above ground, but cuniform-inscribed bricks can still be seen scattered about.

Most famous of all is Ur, home town of Abraham. The lower levels of the ziggurat have been reconstructed. Early archeology was all about verification of the Bible, so a set of nearby foundations has been popularly identified as “Abraham’s House.” I have no doubt about this claim because I checked the name on the mailbox.

We spend the night in Nasiriyah and enjoy a sunset walk along the corniche fronting the Euphrates. The expected foul odor is absent for an unexpected reason: they don’t dump their waste in it. They make no effort to treat it at all so the river does not smell like a sewer; the town does.

The next day we reach the marshes. The Marsh Arabs have led a waterborne existence for millienia, living in reed houses and getting around on reed boats. Saddam drained the marshes, but portions have been restored. We get a too-brief ride through narrow, rush-lined waterways. It’s like the Everglades, but without the alligators.

>

>

At the confluence of the Tigris and the Euphrates is a small walled garden containing an almost-dead, concreted-in tree labled “Adam’s Tree.” I would have been more impressed by Eve’s.

We finally reach Basra. It’s a hot, dirty, seedy, and dangerous place, but, as Iraq’s only port, economically vital. Sinbad sailed from here. We visit the abandoned houses of rich Jewish merchants. After 2500 years in Mesopotamia (Baghdad was one-fourth Jewish), the Jews fled/were driven out in the 1950’s and 60’s. If nothing else, they need to come back and teach these people how to make pickles, which are served everywhere but taste like cucumbers in vinegar.

We also visit a Mandean church, another ancient monotheistic sect. Then, a passage from the sublime to the ridiculous: Saddam’s Basra palace, another oversized pile. This one was also looted and stripped, and then used to billet British occupation troops.

In the evening we take a boat ride on the Shat-al-Arab, the waterway formed by the combined Tigris and Euphrates. We glide past Saddam’s yacht, moored and rusting for at least ten years.

One of our group is flying out the next morning, so it’s time to head back to Baghdad. It’s a full day’s drive with one stop: Ezra’s tomb, an historically Jewish shrine that has been almost but not completely Islamicized. The Hebrew inscriptions are not covered over but have been supplemented by Koranic verses.

Next door is a long-closed synagogue that the caretaker opens for us, disturbing the resident bat colony. He tells us that the authorities want it torn down, but the villagers respect it as an historic site.

We have an extra day back in Baghdad. If you follow the news you would know that Sunday is market-bombing day (Friday is mosque-bombing day), so those places are out. While Al Qaeda is making fresh corpses, we visit the already dead.

First, an old Muslim cemetery near the train station. Some traditions hold that Noah is buried here: I look but do not see any markers in the shape of an ark. Supposedly Joshua is buried here as well, but that is too far-fetched even for me. From the top of the minaret we can see down into the trainyard: Saddam’s armored train is supposed to be in there somewhere – now that would make a good tourist attraction. We can also see looming in the distance the skeltons of Saddam’s unfinished mosques which were supposed to be the largest in the world.

The British War Cemetery is interesting. The British government pays for the upkeep of soldiers’ grave around the world. This one contains soldiers from WWI and WWII. In addition to Tommies, buried here are sepoys from India, members of the Arab Legion, and 400+ soldiers of the Polish Free Army. Being such good sports, they have even erected a monument to the Turkish soldiers who gave their lives to their country.

Most everything built by Saddam is kitsch on a monumental scale, but the Iran-Iraq War memorial is an exception, the winner of an international design competition. It is beautiful and impressive up close and from afar. Although it has not yet reopened to the public, connections get us in.

Engraved on the walls are the names of the fallen. The interior used to contain exhibits glorifying the war (which, after a million casualties, ended in stalemate), but it is being converted to a a museum of the atrocities of the Saddam regime. There are pictures of mass graves being unearthed, photographs of victims, and an almost unseemly fascination with medieval-style torture implements.

For out 10 AM flight to Istanbul we have to leave the hotel at 6 AM – no telling how many checkpoints and problems we will encounter. As it turns out, no delays getting there. The entry road to the new airport is nicely landscaped, having been done up for an arab summit last year. About two miles out all traffic is diverted to a parking lot. That’s as far as we are allowed to go in our bus. All passengers must transfer to buses, or, in our case, a Chevy Suburban. We drive for a bit to a checkpoint. Everyone out while bomb-sniffing dogs go over vehicle and luggage. Drive a ways further, then out with our luggage to go through x-ray screening. When we reach the terminal, we are not allowed to enter. All luggage is piled into a bay while we are ushered into a waiting area. Another inspection by dogs. Airport security has been contracted out to a western firm, so you know they are serious. Finally, we can go inside, which means the usual battery of x-rays and metal detectors. By the time we reach the check-in counter, it is 8:30 AM.

Now the drama. Although we were authorized for visa and submitted our passports when we reached Baghdad, visas were never affixed. What we have is a letter from the Tourism Ministry (in Arabic) that supposedly says that notwithstanding this we are allowed to leave. The guy who left yesterday was our test case: for him the letter was sufficient authority. After checking in for the flight, we go to immigration and show the letter. “What is this?” He calls over a guy in a military uniform who looks at it and says we still need an exit visa, available back in Baghdad. Much arguing ensues. A representative from the Tourism Ministry is supposed to be there to assist us but is nowhere to be seen and doesn’t answer his phone. Twenty minutes later, the clock ticking down, he shows up but is not much help. More arguing. We go to the office. More arguing. Uniform guy then says we can buy exit visas on the spot for $420, which is about right for the eight of us. We assemble the dough. No, that’s $420 EACH. WHAT? That’s ridiculous! More arguing. The Turkish Airlines guy has joined us and is growing increasingly agitated: the plane needs to take off. He tries to collect our baggage receipts so our luggage can be removed from the plane. No way! In a bind, we start to see if we still have $3500 cash left between us. All of a sudden uniform guy barks “Okay! No money!” We grab our passports and hurry back to the counter to get them stamped then race to the boarding gate. The door closes behind us. High drama, happy ending. (My interpretation: the visa fee was going to go into his pocket. He suddenly realized that the risk of negative repercussions was getting high. If we didn’t get on the plane we would become a problem; if he let us go he could go back to drinking coffee. In this instance, better judgment prevailed over opportunism.)

That’s why they call it adventure travel.