I still need to catch the few remaining strays in Africa. An occasion arises when Nomadmania, one of my travel groups, announces a trip to the Central African Republic, one of the most difficult countries to visit. To that, I append the two I still need in West Africa.

The first: Nigeria, a notoriously difficult to obtain tourist visa. That problem can be and is overcome by paying an inordinate sum for a business visa. My qualifying “business”? Discussing "tourism-related matters".

Lagos, the capital of this, the most-populous nation in Africa, can be reached on an easy non-stop flight from the US. Its airport, once a den of corruption, bribery, and extortion, has been cleaned up and is now hassle-free. I am only hit up once – instead of placing my suitcase onto the carousel belt, the loader has put it aside; when I finally locate it he requests “tea money” for “safeguarding” it.

My guide and driver meet me and we drive about ninety minutes, halfway to the Benin border, to Badagry, the focal point of Nigeria's slavery tourism.

Compared to the major slave transhipment ports in west Africa, Badagry was a very minor player, but, as the saying goes, never let the facts get in the way of a good story. Today it is a smallish town that trades on its history, including the first two-story building in Nigeria: a Methodist mission house built in 1845.

There is a Slavery Museum, a Slave Market Museum, and slavery-themed everything. The exhibits consist of generic illustrations you see reproduced everywhere but with no connection to this locale. The ho-hum interior displays are almost redeemed by the cool statute outside.

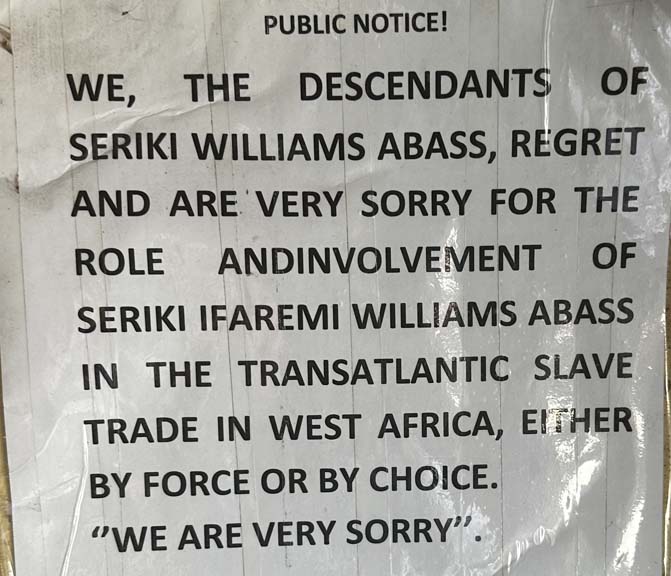

There is one place that I find both interesting and revealing: the museum of the Mobees, a family of black slave traders, exhibiting original chains, collars, and holding pens. The unspoken part: all this stuff is still around to see and hold because slavery continued here until well into the 20th century. Except it wasn’t the trans-Atlantic trade for which they profusely and publicly apologogize and which was outlawed in 1807; it was by Muslims continuing their traditional ways until compelled to stop by the British.

|

|

|

|

|

This crabbed history continues after a short boat ride to a barrier island and a long walk to the Atlantic shore. The fanciful Point of No Return is marked by two concrete pillars, symbolic of a portal and obviously no more than a few decades old. Even more recent is the "Ark of Embarkation," meant to be symbolic of something and now a rusting skeleton.

|

|

|

Before beginning our road trip the next day, I need to change some money. The largest bill is the 1000 naira note, worth about 67¢. The ATMs, when they work, dispense no more than 20,000 naira, so I need a fistful of cash.

The first stop is Olomo Rock, a place of refuge during tribal wars. Rising above the city of Abeokuta, these huge boulders are the center of a tourism complex. The elevators being (permanently) out of order, we join the line of visitors snaking its way to the top.

|

|

|

On the back side of the rocks are some animist shrines. There are not a lot of tourists, but plenty of visiting schoolchildren. They shout "Oyinbo", meaning "white man" in the Yoruba language, and ask for a "snap", i.e., to pose with them for photos.

|

|

|

Wherever I go I am importuned for selfies. I can't help but wonder whether the digital file will be making its way to some computer lab to be turned into a deepfake or used for identity theft or some other nefarious purpose. Time will tell.

In the town is the palace of the Alake of Abeokuta, the traditional ruler of the Egba tribe. In its courtyard are numerous effigies of some vague significance, and a photo shoot in progress.

|

|

|

The Alake is absent, but he has thoughtfully left a cardboard effigy.

|

|

|

A museum highlights various Egba notables and dignitaries. Two thoughts come to mind: 1) there seem to be a lot of chiefs, but not so many indians; and 2) the last thing conflict-ridden Africa needs is encouragement of tribal identity.

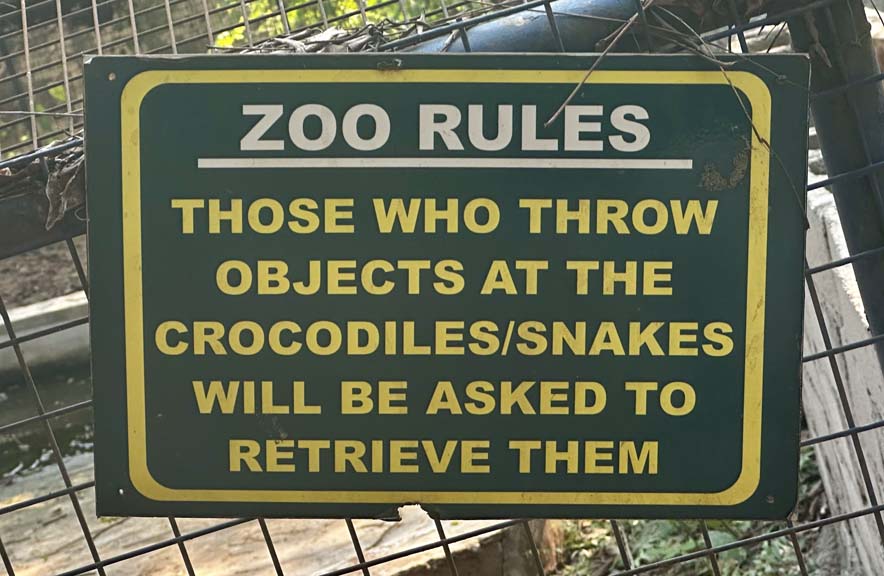

Abeokuta also has a zoo. Some of the animals appear severely underfed and others are not quite rare.

|

|

|

|

|

The next day we continue on to the ancient city of Ife, founded 2500-3000 years ago. The traditional king, the Ooni of Ife, has an imposing palace, but it's not open to ordinary visitors. We have to content ourselves with skulking around its outer precincts.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Also in Ife is the Staff of Oranmiyan, a slender monolith sacred to the Yoruba people. (Keep your filthy thoughts to yourself!)

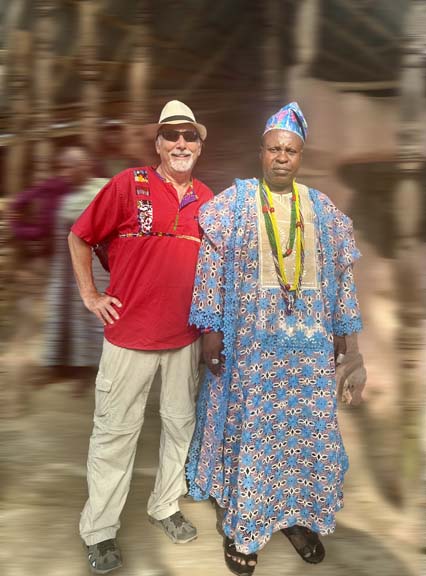

Where we stumble on a celebration.

|

|

|

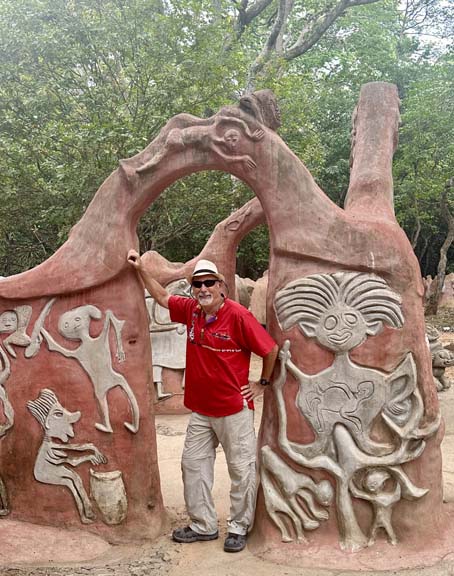

Another day, another sacred grove. We are in Osogbo, home of the Osun Sacred Grove and its fantastical sculptures .

|

|

|

|

|

The forest locale is ancient, but the figures are modern creations by an Austrian women aiming to depict traditional Yoruba spirits. Apparently the litter scattered about the grove is also sacred because no one wants to disturb it.

|

|

|

|

|

We chance upon another festive gathering.

|

|

|

|

|

The next day we drive to the Erin-Ijesa waterfall. The upward path starts off gently but becomes increasingly steep and treacherous. There are seven levels of falls, of which we make it to five.

|

|

|

|

|

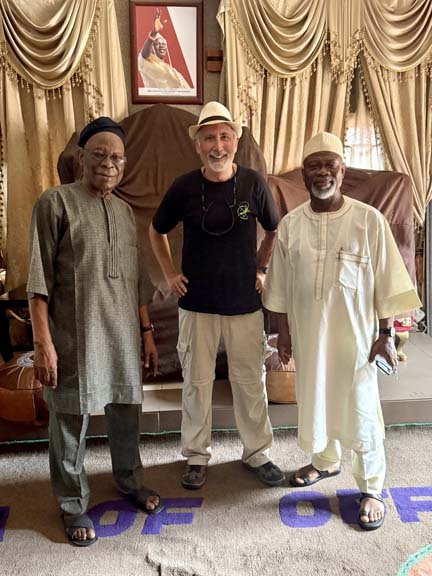

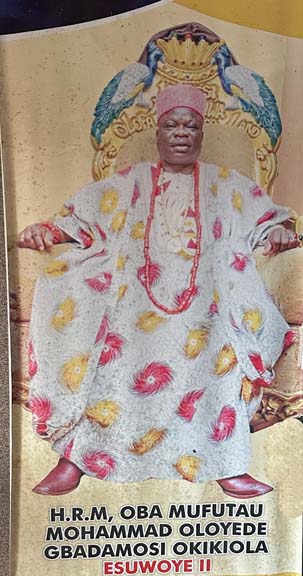

After that, we move on to Offa. In order to visit the palace of His Majesty, the Olofa of Offa, we must first meet with his chief of staff. We "pass" the interview, but HRM is not available for a photo op; his minions stand his stead.

|

|

|

|

|

In the countryside at Esie is the oldest museum in Nigeria, established on the site where approximately 1500 soapstone figurines were discovered in 1775. They are estimated to have been carved sometime between the 12th and 15th centuries. They may be historic and culturally significant, but are neither beautiful nor impressive. All the loose, seemingly interchangeable parts remind me of a grand-scale Mr Potato Head.

|

|

|

|

|

The furthest point on our road trip is Ilorin, where we enjoy the balmy weather. Its central mosque is the second largest in west Africa.

|

|

|

Adjacent is the Emir’s Palace. We are not admitted into the main building, and a guided tour only shows the exterior of subsidiary structures. The tennis court is occupied by a goat. Surrounding it are tiered rows of audience seating. (I wonder if the royal executioner is stationed nearby to execute anyone who fails to applaud the Emir’s prowess.) The security alarm system is a flock of sentinel geese. This being Ramadan, a lot of folks are hanging around in anticipation of a Iftar feast, courtesy of the Emir.

|

|

Ilorin is known for its weaving.

|

|

|

As well as its pottery. The potters' output is hand formed (no wheel used) and fairly crude. Yet, we are quoted prices as if it were fine hand-blown Venetian glass. No wonder unsold inventory is piled about in huge heaps.

|

|

|

We drive back to Lagos. There is, on paper, a national highway system, and in and around the capital it is quite good. Beyond that, the road quality ranges from top notch to terrible to non-existent. This, we are told, is due to corruption -- the money for construction and maintenance is appropriated and some to none turns into actual pavement. But there is plenty of police presence to enforce arbitrary or even imaginary rules: a violation can incur a fine of 50,000 naira, but the infraction can be overlooked by an on-the-spot cash payment of a small fraction of that amount.

Lagos is built on a series of coastal islands. Beneath one of the bridges is Makoko, an informal community (slum?) of 85,000 residents. Every structure and dwelling is built on stilts and all transport and commerce is by and on water.

|

|

|

|

|

A completely overrated attraction is the Lekki conservation center and its thoroughly pointless canopy walkways. Have you ever seen trees from above? Much better is the nearby arts and crafts market where I acquire my mementos.

We wrap up our visit at the much better than expected Nike Art Gallery. Four floors of paintings, sculpture, and other art showcasing the best talent of the nation. Clearly, some of the artists' output is designed for a particular clientele: there are a more than a few huge paintings of men in flowing white robes astride white stallions and wielding scimitars.

|

|

|

|

|

|

After this taste of Nigeria it's on to Liberia, two flights away with a connection in Abidjan. This is not a hard one – with better planning and more time on my last trip I could have continued on from neighboring Sierra Leone.

On the Atlantic coast freed slaves from America set up a society emulating the country they left. Its first eight presidents (all of whom were mulatto and most could have passed for white) were from the U.S. Their national motto, "The Love of Liberty Brought Us Here", did not apply to the indigenous tribes of the interior; they treated those folks pretty much the same as did the Europeans in their colonies elsewhere in Africa (even including some slave-trading).

Until 1980 the country was controlled by an elite consisting of descendants of those émigrés. Then, a violent coup by “African” rebels led to a quarter century of chaos punctuated by two brutal civil wars which cost about half a million lives and brought about a complete economic collapse. Foreign intervention restored order in 2003, free elections took place in 2005, and political stability has endured since.

The international airport is a former WWII US airfield adjacent to the million-acre Firestone Plantation, the world’s largest rubber plantation. Established in 1926, at one time it supplied 80% of the world's rubber. During the war, when southeast Asia was occupied by the Japanese, it was almost the sole source of this vital material.

We drive through the plantation, but there is not a lot to see – there's no visitors center or museum. Our route doesn’t even take us through mature trees.

|

|

|

The next day is our city tour of Monrovia. Its neighborhoods have colorful names: Congo Town, Chocolate City, Chicken Soup. Too bad they don't have signposts.

On a promontory near the U.S. Embassy are the ruins of what was once the only five-star hotel in West Africa, the Ducor Palace that opened in 1960 and later became part of the Intercontinental chain. Looted and abandoned during the first civil war, it was bought by the Libyans who began a total renovation, but the project was abandoned when the Khaddafi government fell. The site is fenced and off limits to visitors, but a small gratuity to the guard gains admittance.

The urban sights are rather limited. The city has never fully recovered from two decades of war.

The showcase Centennial Pavilion, built in 1947 to commenorate the hundredth year of independence, has been fully restored. There we are taught the "handshake of peace", also called the "Liberian handshake", which to me could have been the inspiration for the elaborate comical secret-lodge handshakes parodied in The Flintstones and The Simpsons.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Next door is the National Museum. It displays ethnographic items from the sixteen indigenous tribes and tells the story of the Amero-Liberian settlers.

|

|

|

All this sightseeing gives me an appetite. I haven’t snacked on termites since Burundi. Who should happen by but a street vendor with a wheelbarrow full of the little critters. Ten cents gets a scoopful (To be truthful, they taste like fried nothing.)

|

|

|

|

|

The colonists initially landed on Providence Island. It is now a garbage-strewn park with a monument to the founding settlers.

|

|

|

|

|

The next day, we take a trip to Arthington, hometown to the infamous Charles Taylor, the warlord/President later convicted in the Hague for war crimes. His looted and abandoned mansion lies open to the elements and casual explorers.

|

|

|

|

|

He also built a church, also in ruins. Those looters must have been somewhat god-fearing since they didn’t steal the bell and cross.

|

|

|

|

|

On the last day of this short sojourn we visit the only animal sanctuary in the country. It houses rescued wildlife for rehababilitation and eventual release, mostly monkeys. They specialize in pangolins, but, unfortunately, they were out being taught to forage so we don’t get to see them.

Getting to our final country this trip, the joculary-named Central Africa Republic, requires a seven hour flight from Monrovia across the wide top of Africa to Addis Ababa and an overnight layover before the final leg to Bangui, the capital.

This is a wild and wooly place. It’s not safe to venture much beyond the capital, and there is no tourism to speak of. Foreign diplomats are pretty much confined to their compounds. The country is rich in resources (gold and diamonds), but none of it benefits the people. Street traffic consists of white SUVs belonging to NGOs, luxury cars belonging to the government, military vehicles belonging to the army, UN peacekeepers, and foreign mercenaries, and rattletrap civilian cars. There are armed men and vehicles everywhere, but photographs are strictly forbidden. The government is not in full control much beyond the capital, the remainder of the country being the haunt of various rebels, warlords, bandits, and militias.

Home base is the Khadaffi-built, Libyan-owned Ledger Hotel, a surprising oasis of comfort. Also staying on our floor are a visiting Chinese government delegation. When I get off the elevator there are a minimum of two (sometimes five) security guys in black suits and sunglasses just hanging around. Patrolling the grounds are additional security guys plus their Chinese counterparts. There is quite a difference between the two: one set is focused on looking for threats; the other on looking cool.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the afternoon of our arrival we take a boat ride on the Ubangi River, a tributary of the Congo River. On the opposite shore is Democratic Republic of Congo and the town of Zongo, but, to our disappointment, our visa application was refused so we cannot cross over.

|

|

|

|

|

The next day is a public holiday, so we head out of the city. On the way, we stop at the crumbling Parliament building where the interior is being decorated for the upcoming presidential inauguration. (Spoiler alert: it’s the same guy already in office.) In front is a statue of the country's first president, who was the mayor of Bangui under the French colonial regime until catapulted into national office. He had the grace to die in a plane crash a few months into his term of office, inadvertantly establishing the prevailing Africa institution of “president for life.” He is revered – much of the reason, I suspect, is because he left this mortal coil before he had a chance to become supremely corrupt and reviled.

|

|

|

We are visiting Boali Falls. It is not a disappointment.

|

|

|

The next day we have our city tour. First, the cathedral.

|

|

|

|

|

Then, Russia House. C.A.R. has been called a vassal state of Moscow. The government, who themselves were rebels who succeded in seizing Bangui in 2013, is propped up by the Wagner Group which act as a Praetorian Guard and in return gets free reign to exploit and export gold and diamonds. With their (white) faces concealed, their vehicles race through the streets with impunity.

|

|

|

In front are statues of the company founders, who perished in an “aviation accident” after challenging Putin.

Murals depict the cheerful side of the Moscow-Bangui axis and recall the glory days of the U.S.S.R.

The next day we visit a pygmy village, where we are greeted with an enthusiastic dance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

That's it. Our brief visit is over. We have only seen a tiny corner of the country, but elsewhere is a no-go zone. A flight back to Addis Ababa and a quick connection brings me back stateside.

Trip date: March-April 2025